Dancoland, Part 5: The Two Meanings of Why

Welcome back to Part 5 of Dancoland. If you’ve missed any of parts 1-4, you can catch up here.

Dancoland, Part 2: Just-So Stories

Dancoland, Part 3: Thinking in Layers

Dancoland, Part 4: Everything Loops

This chapter will be the last one of this series.

If you like, you can find the whole series in its permanent home here:

Here we go:

Student: I don’t really know how to ask this, but why did you come here? You never actually told me why you showed up in my dream.

Teacher: So… this is a difficult question for me. But I’m glad you asked. It’s about time I told you why I’m here.

Over this past hour, it’s been so wonderful and inspiring to see you figure out Systems Thinking. At first, you didn’t really get it; but then you worked on it. You kept at it, and you figured it out so well that you’ve surpassed me. I’m so proud.

But, here’s the thing. This doesn’t come naturally to many people your age. Not because people are inherently bad at systems thinking! But it’s hard for people to make that first step, around unlearning cause-and-effect thinking. And I’ve been part of the problem.

Student: How were you part of the problem? You were a great teacher.

Teacher: I really tried my best, and I love teaching. But there’s something about school itself that does people a disservice, I think, when they go off into the real world and have to figure out the systems they encounter. I’ve traveled around, visiting former students, trying to figure out how to teach systems thinking. I never learned how. But then watching you, over this past hour, I realized something important.

Student: Watching me? What did I do that was so special?

Teacher: The big breakthrough, for me, was: you were able to learn systems thinking within the context of a system you already knew.

You see, my whole life I’ve taught kids who have all these different interests. Some of them love the woods; and know so many things about the forest as a system. Some kids love computers; and they understand it as a system too. Some kids love learning languages; some kids just love playing soccer.

What they all have in common is, when they’re inside a system they already know and love, they spend so much time looking around and so much time making things. They spend all of their time thinking about purpose, one way or another: either looking at things and wondering about their purpose, or making things with their own purpose.

Student: Student: You’re right. I’d never thought about it before, but kids are naturally great systems thinkers.

Kids don’t naturally think in terms of cause-and-effect. They think in terms of purpose. They look at the world around them, and say, “The flower’s purpose is to bloom, and the grass’s purpose is to grow, and the sun’s purpose is to shine, and the garbage truck’s purpose is to pick up garbage, and the fire truck’s purpose is to put out fires.”

It’s so simple, and to some people it appears young or juvenile but it’s actually so wise. You and I can see why: “The garbage truck’s purpose is to pick up garbage” is actually much smarter than, “because we put out the garbage, therefore the garbage truck picks it up.” Same for “The flower’s purpose is to bloom.” Or, really, anything: it seems too simple, but when you actually understand the whole system around the flower, you realize, that’s exactly right. The flower’s purpose is to bloom.

Teacher: That’s a great way to put it.

Student: You know when this first gets challenged, though? I don’t think it’s at school; it starts earlier than that.

Let me ask you something: what’s the most famous question that kids ask? All the time?

Teacher: That’s an easy answer. It’s “Why?” Kids ask Why all the time. It’s a well-known thing kids do.

Student: That’s right. Kids naturally ask, “Why?” about everything out there in the world.

But here’s the thing: when kids ask “Why”, they mean one thing; but parents hear something else.

When kids ask Why?, they’re asking, what is the purpose of something. But parents hear: what caused something.

Teacher: Oh wow. You’re right. Kids see the world as made of purpose, but grown-ups see the world as made of cause-and-effect. So the word “Why” means completely different things. Actually, opposite things.

Student: Yeah. I think that’s part of why grown-ups get frustrated answering the endless “Why” questions. Because they get harder and harder to answer, if you’re thinking about them in terms of chains of cause-and-effect.

For grown-ups, “Why” is like a tightrope. The longer the chain of questions, the harder it is to stay balanced on it. It’s stressful.

But kids don’t see it that way at all. To them, Why isn’t a tightrope at all. It’s like a spider web, or a jungle gym. They keep asking why in order to learn, what’s the purpose of that? And that? And that? And each answer makes the web stronger, and more stable, and more fun to climb on and explore.

Teacher: That’s exactly right. But here’s what I was getting at before: kids are naturally such great systems thinkers, and are so naturally curious about the world. They spend all of their time looking around, and making things, in environments that they already know.

But then they go to school. School doesn’t work like that.

Student: It sure doesn’t. In a classroom there can only really be one textbook; one set of lessons to learn, and one problem set to solve. So in order to make that work, you have to take all of the kids out of the environments they already know, and are already interested in, and put them into some neutral context that’s the same for everyone.

Teacher: And so, what do we do in school? We solve problems. We learn there’s a formula for how to do a problem, and then a set of problems with definite answers, and a cause-and-effect relationship between the questions and the answers.

When you initially told me that just-so story about your walking speed and village size, that was familiar to me; it’s the kind of thinking you learn in school. It’s sensible; it proceeds from X to Y to Z in an orderly manner. But it’s not how your world works; or how any world works. It’s tightrope thinking.

Student: Yeah. Whereas if you look at kids in environments where they’re thriving - so could be sports, or clubs, hobbies, their neighbourhoods, or to be honest sometimes it’s even in school, in subjects they’ve really fallen in love with - what they all have in common is they aren’t problem solving. There’s lots of looking, and lots of making, but no trying to “solve” anything.

Teacher: Well, I do know something at the end of all of this. And it’s that I want to thank you for sharing your dream with me. I know I learned something.

Student: I’m really glad you came here. I did too.

Teacher: And on that note, it’s nearly morning. I need to get going soon, before you wake up.

So in our last few minutes together, I have one last question for you: how do we preserve, and regain, that Childhood systems-thinking mode? Where instead of heading down the path of tightrope knowledge and cause-and-effect thinking, we can joyfully play in our purposeful, systems-thinking mindset?

Student: That’s a great question to end on. And I think I have something for you. Two things, actually. One parable, and one piece of advice I heard once. I heard both of them a long time ago, and they didn’t resonate with me at all back then. I never thought about them much before. But now I think they make sense.

The first one is the story of the frog and the scorpion. Do you know it?

Teacher: No. Tell me.

Student: A long time ago, a frog and a scorpion were friends. One day, the scorpion needed to cross a river. He asked the frog to carry him across, and the frog agreed. But then halfway across the river, the scorpion stung the frog.

Frog cried out: “Why did you do that? Now I will die, and then you will drown.”

And the scorpion replied: “I’m sorry. It’s just in my nature.”

Teacher: That’s a depressing story.

Student: It is; or, I guess, I thought it was. The scorpion had a purpose, and he carried out his purpose. There’s no cause-and-effect explanation for why this happened. You won’t find any answers there, or any comfort.

But here’s the second piece of advice, and once you hear it, I think you’ll understand the story in a different light. It goes:

We become the stories that we tell about ourselves.

Teacher: We become the stories that we tell about ourselves?

Student: That’s right. Because the stories that we tell about ourselves become our purpose. And then our purpose carries itself out. If we become the scorpion, it’s because we told a story about ourselves: “I am the scorpion!” And then that becomes our purpose.

Purpose is something that we choose. So it’s important to go find the right one, because the purpose you choose will determine how you spend it, and how you recharge it. And that will determine who you are, in this world.

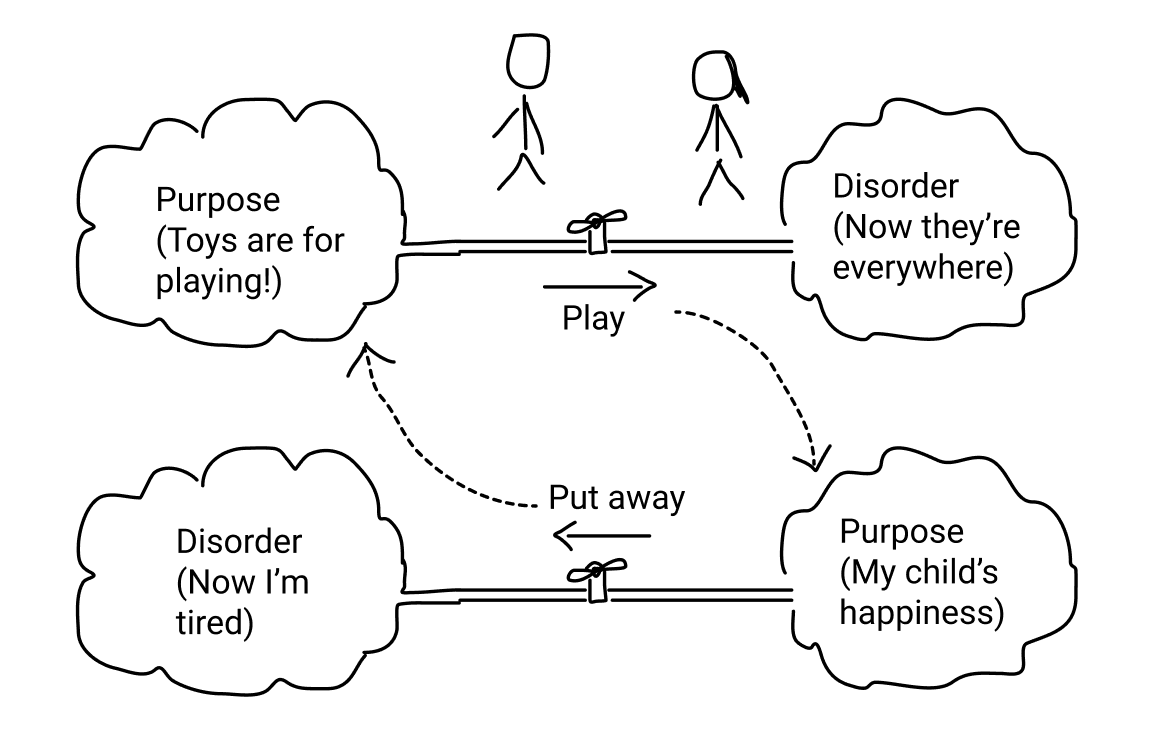

Let me leave you with a simple system to think about. It’s a system with three parts: a parent, a child, and their toys.

Teacher: Sounds promising. I’m ready.

Student: Let’s begin with the toys. Through the eyes of the child, the toys have a clear purpose. They’re to be played with! That’s the point of toys; to play with them joyfully. By playing with the toys, their purpose is spent. They end the afternoon strewn all over the floor, in total disorder.

Meanwhile, through the eyes of the parent, there’s another purpose at work: the purpose of their child’s happiness. At the end of the day, the parent spends their purpose putting the toys away for another day of play. At the end, the parent is tired. They feel spent.

If those systems existed in isolation from one another, they’d reach equilibrium after one cycle. We’d end with the toys in disarray, and the parent exhausted. We’d achieve disorder, permanently.

But these two systems restore one another’s purpose, and that’s why they persist. The parent’s effort restores the purpose of the toys, and the child’s joy restores the purpose of the parent.

Teacher: I think I see where you’re going here. What makes this system work is the parent choosing: “My purpose is my child’s happiness”, as opposed to something like, “My purpose is cleaning up.” One recharges the system; and makes it loop. The other doesn’t. It dead ends.

Student: Exactly. If the parent tells a story about themselves that goes, “I spend all day cleaning up after my kid”, then they’re going to believe it. Not only are they going to get repeatedly tired and cranky, they’ll also be failing to participate in this system, in a meaningful way. The system will find a different, much worse steady state, with a tired parent and a resentful kid.

But when the parent sees their purpose as “I am the parent of a happy child”, then not only will helping out feel like recharging, it’ll also help this system enter new states, like the parent and child playing together, and making things together. The parent will get to participate in the child’s purpose, in the order and chaos of play.

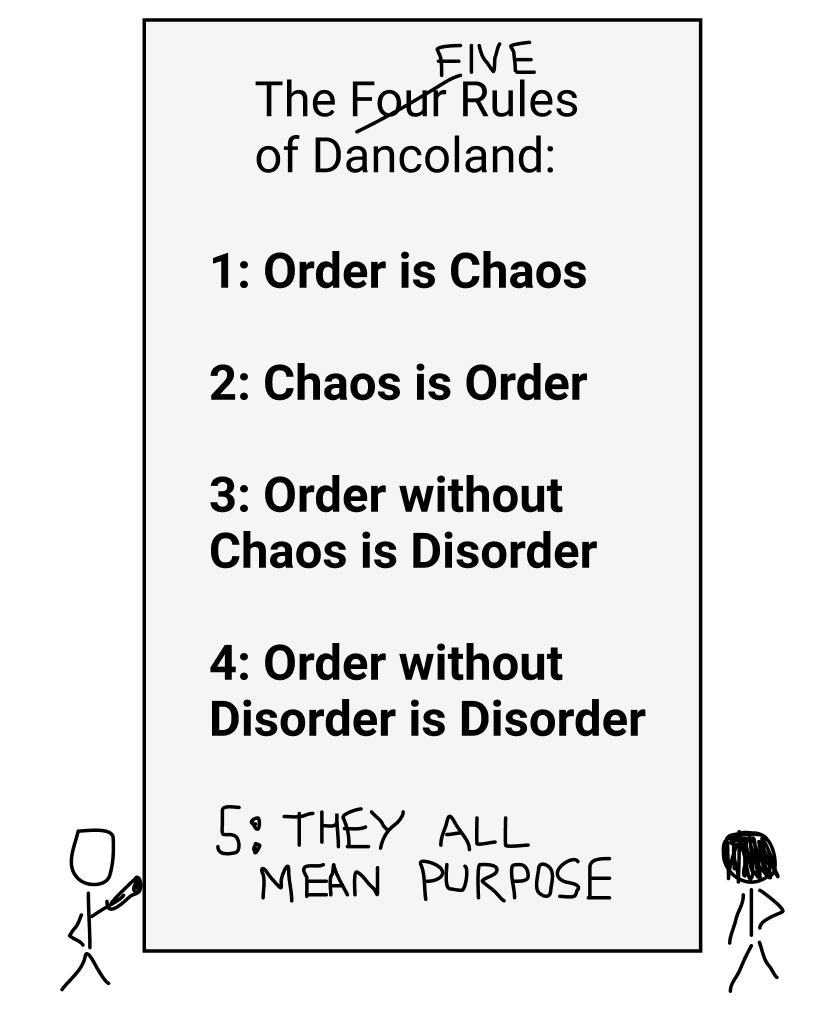

Teacher: I bet this is where understanding “Order and Chaos being the same thing” can really help.

Student: Exactly! That’s one of the best things about being a parent, is appreciating how the child’s purposeful play is simultaneously so orderly (when you look at from the outside in), but also so chaotic (from the inside out) in a special sense: tiny discoveries made while playing can cascade into positive feedback cycles of new interests, new understanding, and a new way of interacting with the world that really changes the world around us.

Teacher: That’s right. Some small detail that a kid notices while playing, or some tiny event that shapes the course of a playful afternoon, could massively change how that kid goes on to experience and appreciate the world. It’s the best kind of chaos. Not only is it Purpose that recharges Purpose (the parent’s), it’s also Purpose that creates new Purpose (the child’s).

Wow, all of those lessons from our time together just came together all at once there.

Student: Kids show us the way, don’t they.

Teacher: They sure do.

Student: All right, I guess we’d better go. But I’m thinking we should probably leave something behind.

Teacher: You read my mind. Do you have a pen?

Student: Sure do.

The teacher and the student both smiled. They knew their time was up; it was morning. The student started to wake up. But before he did, there was one last thing he had to do, which was pack up this whole entire dream - the farm, the furnace, the bugs, the layers, and everything else - and put it into his Backpack of Knowledge. He had a feeling he might need that backpack another night, for another dream. Some day.

And then he put on the backpack, and woke up.

Thanks for reading along. You can find a permanent link here:

The ideas in this series are based on the book Order out of Chaos by Ilya Prigogine, who won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1977. It’s been fun trying to translate these ideas into a more approachable narrative and setting.

This story first saw the light of day (in early draft form) in an Interintellect Salon I hosted back in May. It was a ton of fun, and I think going forward this is how I’ll work through these longer-form ideas: first in a semi-private salon, with a friendly audience, so we can work the bugs out, and then in the newsletter later.

The next one of these Dancoland series is going to be all about Information. It’s going to be good. I’ll be hosting a salon on September 1st, from 1 to 3:30 EST, to share it with any of you who’d like to join. I’m going to cap it at 30 or so attendees, like the previous ones, which seems to be a really nice group size for these events.

You can register here:

The Medium, The Message and the Mind | September 1st, at the Interintellect

Have a great week,

Alex