Dancoland, Part 3: Thinking in Layers

Welcome back to Dancoland. If you aren’t caught up, head here to start at the beginning.

Last week, we’d learned how different systems can find their own steady states, and how order emerges when systems flow. But hadn’t really gone below the surface in search of real secret of Dancoland. For instance, we haven’t yet talked about the bugs.

Student: There’s something I don’t understand yet. And that’s why you showed me the bugs.

Teacher: The bugs certainly don’t seem like they’re in a steady state, do they.

Student: Not at all. They’re growing, evolving, and changing their environment all the time. It looks pretty chaotic and unpredictable. Maybe we can illustrate this with another system diagram. I’m not sure where to start though.

Teacher: Well, what is the main thing flowing through the system?

Student: I think it’s also nutrients. What’s a bug, after all, other than a sophisticated system for turning nutrients into more bugs?

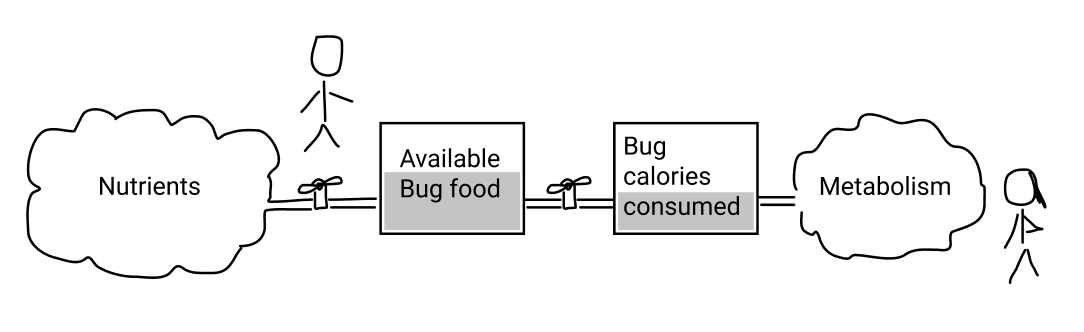

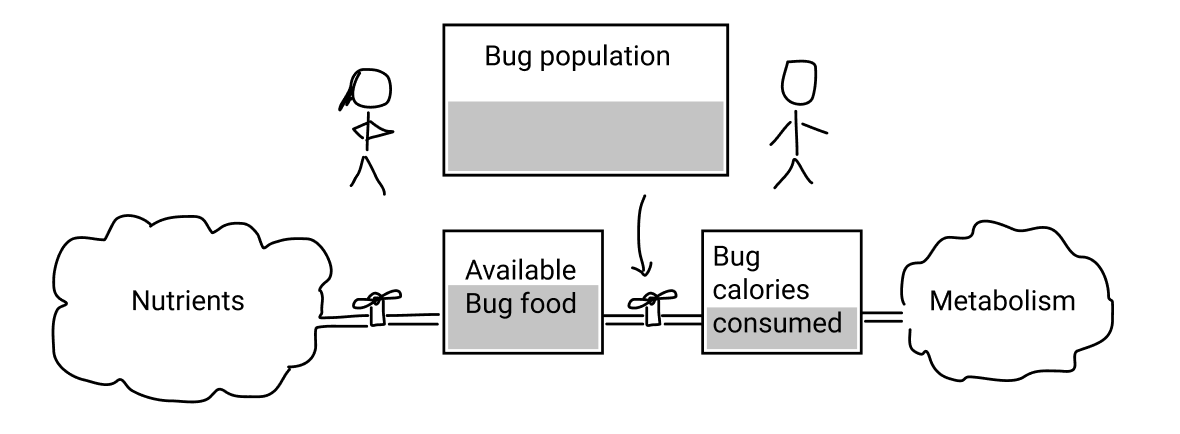

Ok so let’s draw this out. Nutrients start their lives out in the environment just like before; and they end their lives consumed by the bugs’ metabolism. In between we’ve got a couple of stocks where it’ll accumulate along the way.

And let’s also put a large stock of bugs called Bug Population, which affects how quickly the nutrients get eaten.

Teacher: Anything else we know about that affects this stock-and-flow system?

Student: Sure. So the bugs live in a complex environment; they don’t have it easy. There are predators who eat the bugs. And there are competitors, who eat the bug food. The larger either of those stocks get, the more pressure it puts on the bug population.

Teacher: So far this looks good. But let’s get to the important part here, which is the fact that the bugs reproduce and evolve. There’s an important concept we haven’t talked about yet, called positive feedback.

Student: Ok, let’s draw this out carefully. Bugs reproduce by laying eggs. When they’re happy and eating lots, they lay a lot of eggs. Then, those eggs hatch into baby bugs at a certain rate, and they flow into the mature bug population.

That’s a reinforcing cycle. More of the same makes more of the same. If it goes on forever, you get infinite bugs. So clearly that must stop somewhere; either because they run out of nutrients, or the predators, or too much competition, or something.

Teacher: Now remember, the bugs don’t just reproduce; they also learn and evolve. They’re actively learning how to change their environment to their advantage, aren’t they.

Student: You’re right. Not only do the bugs make more bugs; they make more evolved bugs. And those evolved bugs are making tools and technology to alter their environment. Some of their tools help defend them against predators; some of their tools help them grow bug food faster.

The bug ecosystem is totally thriving. Lots of food means lots of eggs, lots of new bugs, and more evolved bugs. This system seems like it could totally go on for a long time; now that the bugs have learned how to build technology and alter their environment for their benefit. I can’t say for certain that any of the environment around them will survive intact, mind you.

So I guess I’d say that the long-term order and stability of the bugs - so, in other words, the fact that bugs can perpetually make more of themselves in a predictable way - feels inseparable from the environment around them being unpredictable.

Teacher: Hold up. There’s a lot in what you said just there. I want to make sure this doesn’t fly by without us noticing. Maybe we’d better critically examine what you mean by “predictable” and “unpredictable”.

Student: Right. So, when I’m saying that the bugs are “predictable”, I mean that what I see now - bugs making more bugs - is a pretty good prediction of what tomorrow’s or next year’s bugs will look like. Just like how our farm was orderly - our farm this year is pretty representative of our farm next year. Or the building that hosts the market is predictable - the building today accurately portrays what the building is likely to be tomorrow, with maybe only small changes.

The order comes from self-perpetuation. There’s always something driving the system forward, so that like makes like.

But the environment around the bugs is not predictable. Tiny changes today might cascade into massive changes in the future, because positive feedback can amply things so powerfully. Look, we can see the bugs right in front of us; they’re radically altering the ecosystem around them, with all these interesting second-order effects.

This must be what they mean by “chaos”. Tiny movements on one side of our system drive really big changes on the other, and those big changes drive other changes in our system somewhere else.

Teacher: How would you describe the difference between order and chaos?

Student: Hmm. This feels like an important question. I want to say, based on my experience, that systems are either orderly or they’re chaotic. But given our conversation so far, I’m getting this nagging feeling like that’s not true. It feels suspiciously like calling systems orderly or chaotic is actually a symptom of cause-and-effect thinking that I need to move past.

Teacher: Go on.

Student: Just now, when we went back to look at the bugs, the big idea we introduced was positive feedback. Like makes like. Bugs make more bugs. It’s a driving force, it’s like a sense of purpose for this corner of our system.

When we introduced this idea, I’d initially thought of positive feedback as this driver of order; like it drives alignment in a system. When I see bugs reproducing today, I know that I will see bugs reproducing tomorrow, and the day after that. When a group of people align around a purpose, that’s a kind of order.

But at the same time, positive feedback seems so dangerous and chaotic. When something in a system makes more and more of itself, that can rip the system apart, in some way you’ll never ever be able to predict. Positive feedback is clearly the driver behind systems that tip into chaos; like crowds that panic, or non-native species that invade new ecosystems. When a group of people all suddenly align around an idea or a purpose, that can be really unpredictable.

I’m not sure how to resolve these two ideas. But I know they both have something to do with growth, and with evolution. The bugs are a positive feedback system that makes the future both more predictable and more unpredictable. Depending on where you’re looking. Again, this feels like a cause-and-effect symptom that’s trying to fight for its life, as I’m trying to shake it off.

Teacher: I’m glad you mentioned that word, evolution. You’re on the right track. Is there anything we saw, in our travels together, that might resolve this paradox for us?

Student: Maybe. You know what, this actually reminds me of when we saw the city by the sea, that seemed so strange and advanced to me.

That city, and the market, and the whole system around it evolved, just like the bugs evolved. That market evolved because people need to eat; and it keeps existing because people continue eating. It has an ongoing purpose.

But that’s true for farming too. The market didn’t displace farming. It emerged as a new layer on top of farming.

Student: I’m not going to try to work out the new steady states it might find right now. But I’m sure that as the market evolves and settles into its own steady state layer, the Farming Layer next door responds by finding a new steady state of its own, and adjusting its purpose. That must have been an interesting transition.

Teacher: You’re on the verge of completing this breakthrough, and I want to push you here. I want you to think about that phrase from before: Order emerges in the steady-state of non-equilibrium systems. Remember that? It was a big concept.

Now I want you to take that concept and tell me about the bugs, and how the bugs evolve.

Student: Ok, the bugs are a layered system, just like the farm and the market. Their metabolism, cells, tissues, organs, and individual selves are all layers with their own systems in steady state. And beyond the individual bugs, they organize into communities, they make tools, they invent technologies. Each of these layers is its own system with its own purpose, but they all exist in context with all the other layers.

So maybe we should attach an addendum to our motto: if order emerges in the steady-state of non-equilibrium systems, then evolution is about emerging, multi-layered steady-states of non-equilibrium systems.

Teacher: I couldn’t have said it any better myself.

Student: I think I suddenly see my problem. It’s a problem with the way I’ve been using language, and with the words “predictable” and “unpredictable”. I’ve been using the terms in my old cause-and-effect way, like A predictably causes B and then C, or A unpredictably causes “?”. The problem was the word cause!

I see now. That’s why you asked me to critically examine the words “predictable” and “unpredictable”. I guess I didn’t totally pass that test; I still had some lingering cause-and-effect symptoms. I’m not 100% sure how to recharacterize them, though.

Teacher: Maybe we can find a good definition together. Tell me: where do layers come from? I think you already know everything you need to answer this.

Student: When I think about the market as a layer that emerged; it came from positive feedback. The market is a great idea; so it perpetuates itself, and makes more of itself; and copies itself across many different cities and use cases. So at some point it made sense to think of it as its own layer, distinct from farming; and to think of it as having found its own steady state.

And when I think about the bugs, I guess the lowest “layer” I can think of is probably the bug’s metabolism; which is basically the part of the bug that eats, in a really primitive sense. But at some point, some aspect of the bug’s metabolism started making more of itself, and more and more, and at some point it made sense to call that a “cell”. And then as the cells made more of themselves, they became organ systems and then bugs and then bug communities.

So I guess where you were probably hoping I’d get to is, new layers emerge from positive feedback cycles. When something persists, and makes more and more of itself, and starts to significantly change the system around it, it starts making sense to call it its own layer. And that’s useful for us, because we can try to understand that layer as its own little system that’s found a steady state, or is on its way to finding one.

Teacher: So, when do you think a layer officially becomes a layer? What gives a new layer its identity, as it comes into its own?

Student: I mean, I’m not sure you can formally draw a line and say, before this line it’s not a layer and after the line it is. But I can say this: before crossing the line, there’s no way to know what the layer will be. And after the line, we know what the layer is, because the layer has a purpose.

We can say, the purpose of the farming layer is getting nutrients into plants and plants into harvests. The purpose of the market is getting harvests into baskets. The purpose of the bugs’ metabolism is consuming calories. The bugs’ tools have purpose, and their community has purpose. Every layer has a purpose.

And we know these layers have continuous purpose, because they’re not in equilibrium. They flow. That is their purpose. And we know they’re out of equilibrium because the layers around them are out of equilibrium. All the way down to the bug’s metabolism; or the plants’ nutrients; and then if you go down further than that, all the way down to the furnace of the universe.

Huh.

Oh wow.

The student fell silent for a minute.

Student: Okay. Let me collect my thoughts for a second. But I think things fell into place. I think I understand the Four Rules now.

Taking next week off, but when we return, we’ll open the door and see how Dancoland works.

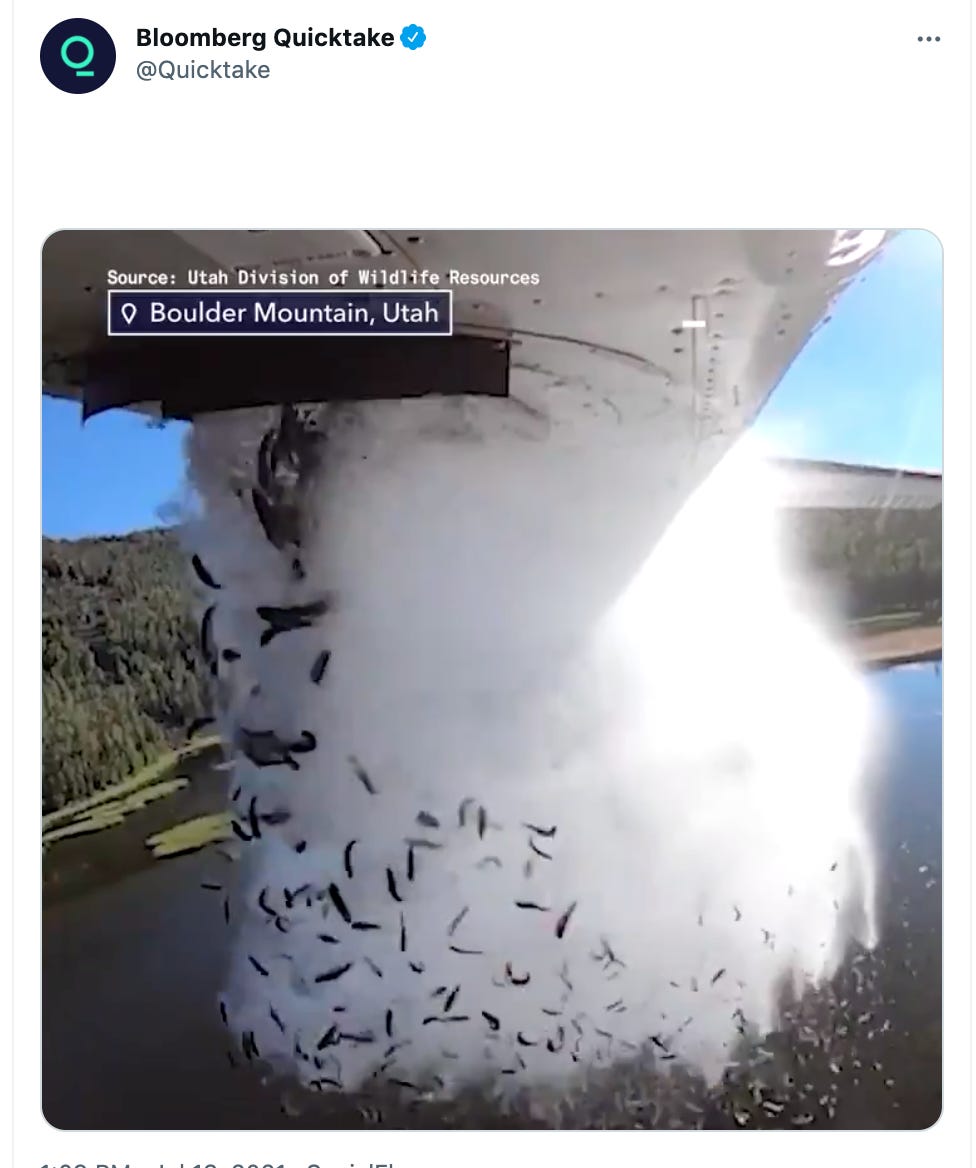

Before we head out, here’s this week’s Tweet Caption Contest:

Congratulations to Reid C., from Palo Alto, for submitting the winning caption:

“Fish stocks only go up.”

Our current finalists, for voting consideration:

“This return to the office policy is a real drag. See you tonight, darling!” -Friedrich, from Toronto

“Hurry up and fix it, we need to beat Bezos!” -Ahan, from SF

“Hey there! We were just reading your tweets.” -Claire T, from USA

And finally, this week’s Tweet:

You can vote and submit your responses here.

Have a great week,

Alex