One problem I think about a lot (as a clear non-expert) is how land use and transportation patterns are evolving into a new kind of inequality wedge in North American cities. There’s no doubt that many cities here in the United States and Canada are enjoying an urban renaissance: industrial and waterfront areas are getting revitalized; downtown is a cool place to live again; walking or biking to work is a desirable goal.

Meanwhile, there’s this chasm of inequality of opportunity that’s opening wider each year, especially in these trendy tier 1 cities that feel like they're arranging themselves into economic caste systems. Commuting has something important to do with it.

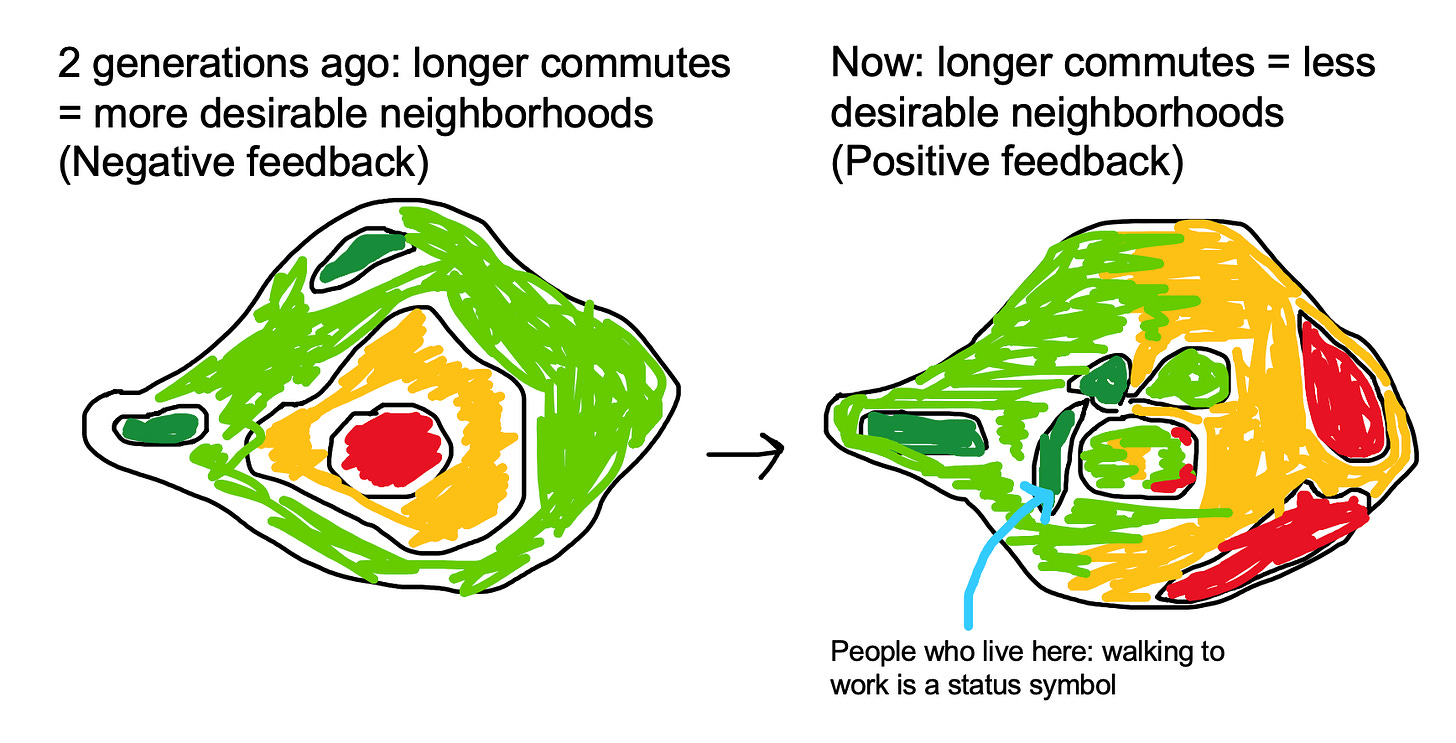

In the 60s and 70s, remember, cities were seen as undesirable. The goal was to live in the suburbs; farther away was more desirable than closer in. As I’ve talked about before, this spatial arrangement had a useful side effect: commuting distance was a part of the cost you had to pay to live the good life. But now, we’re going through this big inversion where downtown is cool again, and we’re losing the self-corrective mechanism we used to have.

Now if you can’t afford to live downtown, you get forced out towards cheaper real estate, and you’re the one who has to pay the cost of commuting distance. What used to be a negative feedback cycle between commuting and residential desirability has flipped into a positive feedback cycle. (European cities have looked like this for a long time. The really poor areas have been out in the forgotten suburbs for a century.)

This positive feedback cycle, I suspect, is acting as a real economic inequality wedge. It used to be that anyone could move to a city and increase their earning power; nowadays, the economic advantage of cities is only really available to people on the top half of the income spectrum. Most of the discussion around this phenomenon is around specialization of jobs and skills, but I think there’s another factor increasingly at play here: if you can’t afford to live in the attractive part of cities, you’re going to have to pay a “commute tax” that’s going to be a real drag on your ability to prosper and build a good life. High earners consciously pay a premium to avoid this.

Meanwhile, public transit has become popular again. I say “popular” not because public transit ridership is increasing (in many cities, it isn’t) but rather because it’s become a socially virtuous, progressive thing to care about. In the past couple decades there’s been a lot of interest among city planners, the downtown crowd, and the “urban rejuvanists” around a new public transit form factor: the LRT, or Light Rail Transit.

LRT lines are propping up all over the place, and you’ve probably taken some: cities like Denver and Minneapolis have invested a lot into building out LRT networks, and even Phoenix – the ultimate land of the car – built a line recently that’s been quite well received. They’ve come to represent a particular kind of “popular environmental urbanism”: a mix of eco-mindedness and sophistication. Light rail is one of those things you’re just supposed to embrace; or else turn in your Progressive Citizen credentials and admit you’re an eco-terrorist.

But not everyone is excited about them. The Koch brothers, of all people, funded an anti-LRT campaign in Phoenix, and cities like Nashville have voted down initiatives to put in light rail lines. And you know what? I have some issues of my own.

My worry is that LRT lines, in many cases, are a good example of what progressive people think lower-income people want. But their impact is the exact opposite: they gentrify public transit into something that magnifies inequality of opportunity rather than equalizes it. In practice, they’re a luxury option for rich people, rather than something for everyone.

How so? Before we get into what’s going wrong, we need to first get anchored about what a successful public transit system looks like in a North American context.

A lot of North American public transit advocacy can feel like a perpetual lament that North American cities aren’t laid out like European ones. So it’s worth looking at an example of a North American city that’s laid out pretty typically but where the public transit system still works well: Toronto. Although it’s currently going through a huge population and density growth spurt, for the better part of the 20th century Toronto was an average-sized, sprawling, suburban, mid-continental city that didn’t really stand out in any way. It’s a city that’s generally organized around the car.

However, if you look at Toronto’s transit system (the TTC) and how many people use it, it doesn’t look like a classic sprawl city anymore. The subway network doesn’t look all that impressive at first glance, as there are only two “real” subway lines (with two more branch lines on the outskirts). But it has huge ridership, for North American standards. Total ridership is behind only NYC and Mexico City. No other city except Montreal comes close; which makes sense, given Montreal is much more European in its layout and mindset around public transit.

Where are all these riders coming from? Subways are great for moving large numbers of people from one place to another, but they’re a lot less useful if you don’t live and work within walking distance from stops. In a dense city like NYC or Montreal, that’s not a problem, since there’s a critical mass of people living in any given square mile to justify digging an expensive underground subway stop there. But in a low-density, sprawling city like the rest of North America, you can’t easily justify the cost of extending a subway through low-rise neighbourhoods of single family homes.

However, as the subway network was getting built out in the 60s and 70s, the regional Toronto Metro government (whose influential constituents were largely suburban homeowners) got upset that the developing suburbs were left out of the downtown network, and demanded good transit coverage. And they got it: an extensive network of frequent, reliable bus service that covers essentially every major street in the city with 10-minute or better service, all day.

Buses are a good form-factor for serving North American cities outside of their downtown cores, it turns out. They’re flexible, inexpensive, and when properly funded and managed, can be a really solid transit option that genuinely competes with car ownership for getting downtown, or to the subway. They’re not fancy, but they get the job done. It turns out when people say they don’t like taking the bus, what they really don’t like isn’t the bus itself, but mostly bus schedules that are unreliable or infrequent. High frequency, prioritized bus service is actually quite popular when done right.

The extensive bus coverage lets transit planners squeeze every inch out of the subway, too. Practically every subway stop in Toronto outside of the downtown core primarily serves customers who do not walk to the station, but instead take a bus for their last mile. So suburban subway stops still get real ridership, because they can attractively serve a large catchment area. A recent Citylab piece used the York Mills subway stop as an example. It’s next to a golf course, in a low-density neighbourhood. It should be a terrible spot for a station. But the extensive bus connections feeding into it draw in well over 10,000 riders per day, which is more than most subway stops in Brooklyn and even some in Manhattan.

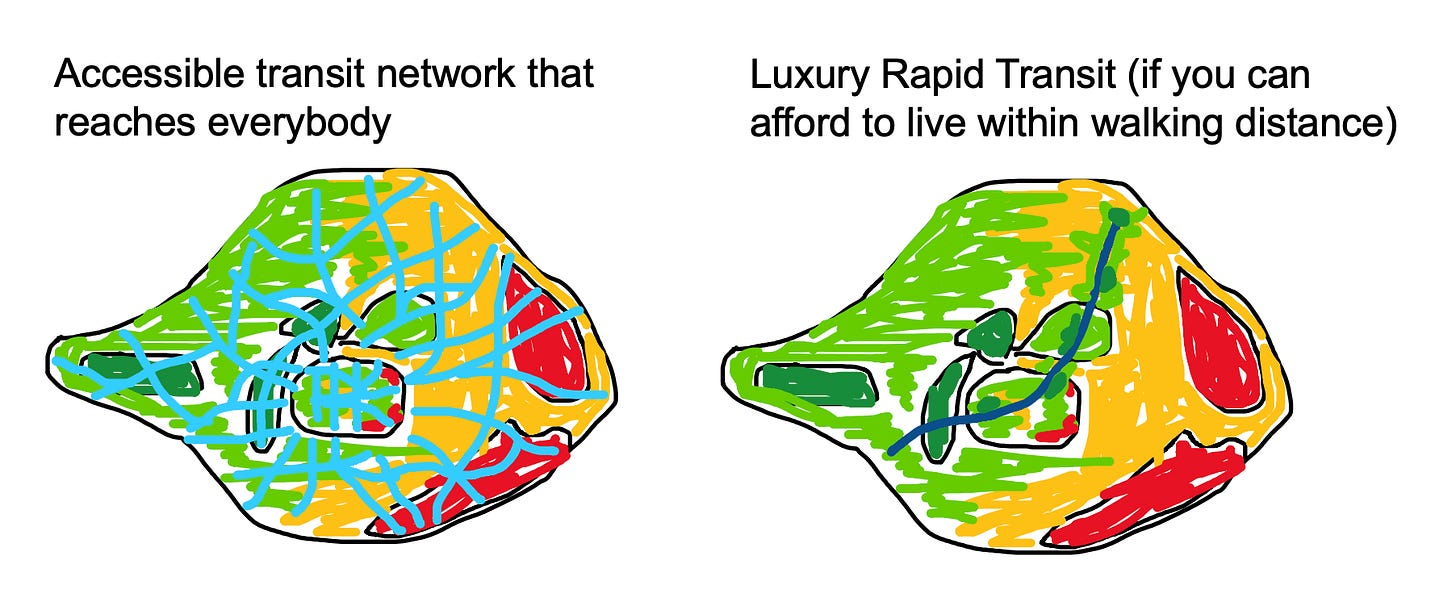

The buses matter. Well-run bus routes can cover a lot of territory, and they can move a lot of people so long as there’s somewhere sensible to take them. Virtually everybody in Toronto lives within walking distance of a solid bus or streetcar route: not just people in gentrified areas, but also everybody in the lower income northwestern and northeastern shoulders of the city that downtown people rarely visit.

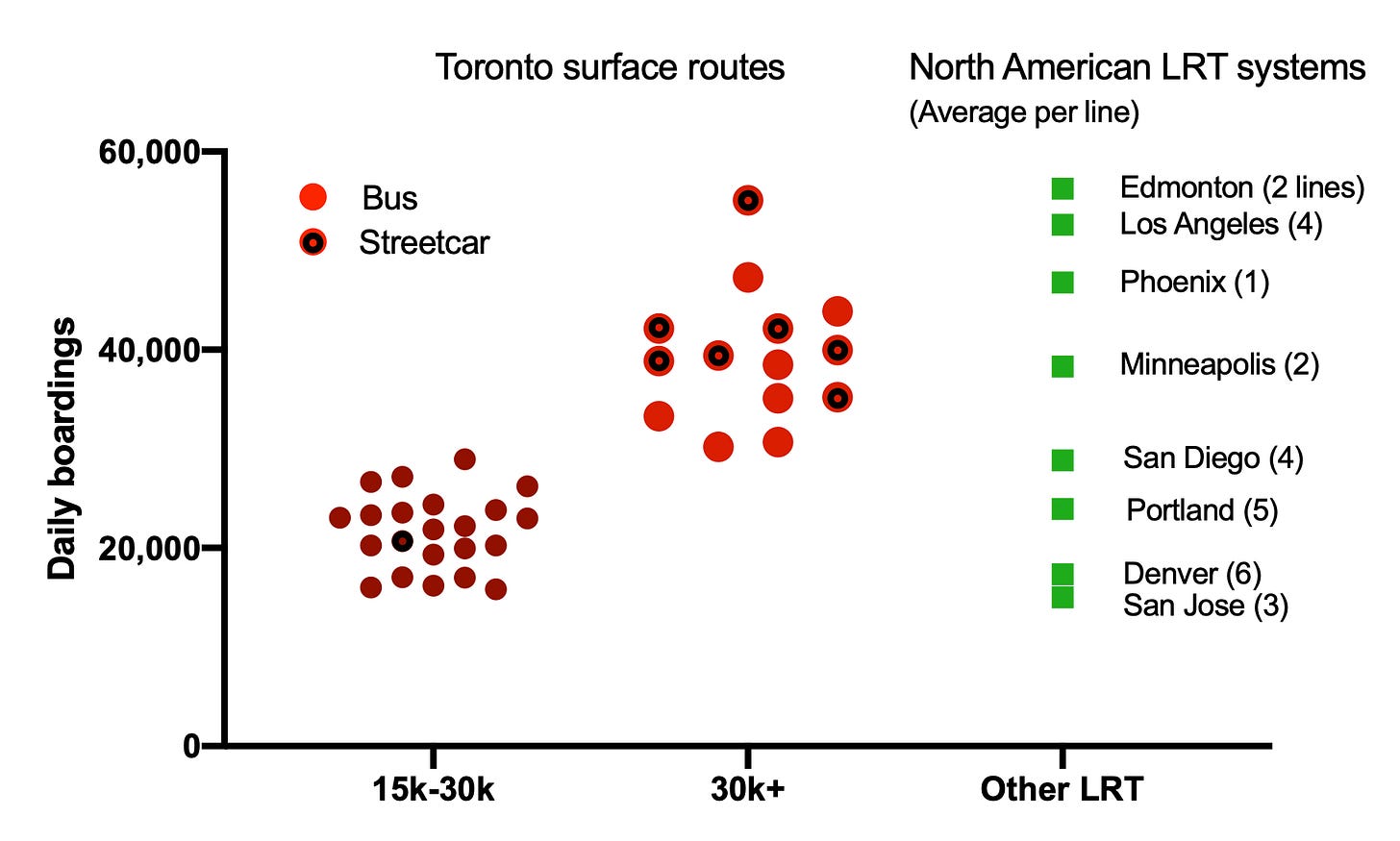

Remarkably, out of the 23 surface transit routes in North America that move 30,000+ people per day, 12 of them are in Toronto. Even if you exclude the downtown streetcars, which operate basically like larger buses on rails, there are 26 distinct bus routes in Toronto that move more than 15,000 people a day each. (And another 59 routes that move more than 5,000 a day, which would be a hugely popular bus route in almost any other city.)

Anyway I’m going through all of this to say two things. First, you can move a lot of people by bus if you need to; the TTC is a good demonstration that large numbers of people will take bus routes for their regular commute if the network is well-run and gets them to where they need to go. Second of all, unless your city is really dense or you have infinite money to spend, any public transit system that wants to actually provide coverage across the entire city is going to need a good bus network.

Fortunately, it’s relatively easy to set up a bus route that works well. You need buses, drivers, and some paint to make dedicated lanes and transit priority intersections. The cost just isn’t on the same magnitude as expropriating land, ripping it up, putting in rails, and then running trains all day.

So this brings us to LRTs and their recent popularity. “If we want more people to take public transit, we have to make public transit nicer!” goes the argument. I’ll happily admit: LRTs are very nice! They’re smooth, comfortable, and definitely a superior rider experience over the bus. They get credit for helping to spur rejuvenation (read: gentrification) of main streets and central areas.

But here’s the thing: they’re not actually moving that many people. LRT lines are getting daily ridership in the tens of thousands, which sounds great, until you remember that a well-designed bus route can easily carry that many people. In North America, compare a sampling of popular LRT systems’ average ridership per line to the more popular TTC bus routes:

(A few notes on methodology here. First of all, for people who know the TTC, I separated out the 504A and 504B so that they’d fit on the graph; otherwise it’d break the y axis. Second, for the other North American LRT and surface rail systems I did a highly quick and imprecise method of taking their total number of daily boardings divided by their total number of routes (in brackets); this is obviously not a very precise way to graph them but it does give a general sense of ridership loads being handled. The point here is that these LRT lines are handling passenger loads that a well-designed bus route could handle no problem.)

These LRT lines, as nice as they may be, are not really being designed or used as building blocks for true higher-order transit systems. They’re more like… a luxury bus. And I don’t want it to sound like I don’t like the idea of a nicer bus! But we should be clear that the real civic purpose of these LRTs isn’t building out the kind of high-capacity backbone trunk routes that you need in an actual at-scale public transit system. Nor are they doing the job a bus network does of crisscrossing the entire city and providing continuous service to every resident. What an LRT line accomplishes is nice, clean, lovely service along the length of the line – but that’s it.

Unfortunately, these LRT lines soak up a lot of money from cities’ and transit agencies’ capital and operating budgets. This is money that could be far better spent, on a per-rider basis, on operating good bus routes; but instead is going to be spent on beautiful, brand new lines that only serve a relatively small catchment area unless they’re already integrated into a dense transit network (which is rarely the case).

The area around the LRT lines definitely attract investment, but if you look at who actually uses the line a few years in, it’s mostly rich people. Why? Because they’re the only people who can afford to take it – not because the fares are too high, but because real estate in the immediate walking area around stations becomes too expensive.

There’s an argument you hear a lot: “The ROI on these lines are great; just look at the increase in property values that follows!” Yeah, exactly! Spending money on LRT lines means spending money in order to make public transit less accessible, not more. For public transit to be accessible to you, it needs to be a real option. Unless you have bus routes or other last-mile ways of getting to the LRT, then it’s going to be a public transit option that’s only available to people who can afford to live nearby. And the nicer you make the line, the higher an income threshold that’s going to require. (Unless you do the hard work of actually integrating the LRT line via last-mile bus routes into all of the other neighbourhoods that aren’t gentrifying.) LRT investment on its own doesn’t expand public transit; it gentrifies it.

What really pisses me off about this is that the biggest proponents of these light rail lines are usually progressive, urban, “forward-thinking” brunch people who can be quick to lecture you about driving or using too many plastic bags or whatever. They love the idea of public transit – except when it’s a bus, of course; you’d never catch them dead riding the city bus.

The LRT lines they advocate, in practice, are essentially a highjacking of the public transit system: reprioritizing funds away from buses and transit networks that actually serve a diverse ridership, and into these Luxury Rapid Transit lines that look nice and pretty and socially progressive, but actually shut out public transit to anyone who can’t afford access to it, forcing them back into cars and into traffic.

It gets worse, actually, if you look at cities like Phoenix who build LRT lines that initially connect affluent communities and then try to expand lines into lower-income areas. Business associations and homeowner associations will stop at nothing to block that kind of progress – “it brings the wrong kind of people into our neighbourhoods”, yeah mmhmm. We’ve heard that one before.

The proof is honestly in the ridership numbers. If an LRT line is carrying a daily load of passengers that could be handled by a bus route (as nearly all of them could be, and are, here in Toronto) then its purpose for existing isn’t “higher order transit”, it’s “luxury public transit”. Again, spending money on public transit infrastructure is something I’m generally going to agree is an attractive idea. But a lot of these LRT lines are being built for the wrong reasons, and they’re having the wrong kind of impact if you care about having a public transit system that actually serves regular people.

The broader lesson here is that a lot of our progressive-minded civic actions and priorities, which seem to locally be something that helps out everybody, are actually having the opposite of the intended effect in the long run. In theory, an LRT system is something that anybody can use; in practice, they start to become virtue toys for rich progressive people. When you look at the LRT itself, it looks great! It looks like everything we’re supposed to be doing. It’s a public transit investment, it gets people out of their cars, it in theory ought to help increase interaction between people they wouldn’t otherwise encounter.

But in practice? If you’re taking public transit, look around, and notice that it’s all rich people – well, you might be witnessing the gentrification and luxur-ification of a public good in real time. The current urban renaissance is amazing, and I’m certainly a beneficiary, but I hate to see it become this “cities as luxury goods” trend. If you ask people what they want and they say “I wish the bus came more frequently”, sometimes the best thing to do is take them at face value, rather than counter with, “Oh, what you actually want is this beautiful expensive train.”

Even here, with our historically humble but high-functioning transit system, we’ve gotten excited about new theoretical expansion while letting our existing networks burst at the seams under wear and overuse. (At least the crosstown LRT being built is projected to handle 150,000+ people per day, which is a much more real number for higher-order transit, at 50% more projected use than the entire 6-line Denver LRT network.)

The best news in public transit here isn’t in Toronto; it’s actually in the suburbs. The city of Brampton, west of Toronto and home to a half million people in its own right (it’s in fact the second fastest growing city in Canada) has seen their own public bus network growing at double digit percentages, serving over 100,000 riders daily – despite the fact that it’s as pure car country as you can possibly get. Other cities in the greater region, like Mississauga, are seeing starting to see similarly impressive ridership gains after decades of car dominance. It’s simple, it works, and it’s popular. Who said public transit couldn’t work in sprawl city? Maybe the key is to build stuff that actually reaches people where they are, and not just vanity transit gentrification projects. But what do I know.

Permalink to this post is here:

Why I don’t love light rail transit | alexdanco.com

A quick note here - if you liked last week’s post on Positional Scarcity, I bet you’ll like the book I’m writing! It’s called Scarcity in the Software Century. I’m currently writing it week by week (albeit a bit spottily over the last couple months as we adapt to life with a newborn, but I’m getting back into the swing of things), and you can support the project by subscribing to it here. This past week, we looked at another kind of emergent scarcity, Integral Scarcity, that naturally and inevitably emerges with abundance:

If positional scarcity was “in conditions of abundance, your place in line becomes scarce, and line-management is great business”, integral scarcity covers a whole other set of issues: “abundance leads to complexity, complexity leads to problems, and those problems are great businesses.” If you’re interested in learning more, I’d love to have you as a subscriber!

Here is a really interesting finding from the biology world:

The short version of what this study is and why they did it (as explained by the senior author on Twitter; and while we’re at it, WOW is Twitter great for research! I can’t imagine how things might have been different if academic science twitter was a thing when I was in grad school. Ah well…):

So, you probably know that most big clinical trials for new drugs fail. It’s especially bad for cancer drugs, where 97% of all hypothesized drug treatments, which were all backed by lots of basic science and had a plausible mechanism for action, do not bear fruit when tested for real medicine. Our understanding of cancer is mostly organized around genes associated with cancer, which we call oncogenes. A certain gene might code for a protein that, when expressed, tells the cell to start dividing and never stop; that’s a cancer gene. So we try to go after those genes with drugs that, through some logical biochemical mechanism, disrupt the cancer process. Hopefully all this makes sense.

The authors of the study looked at this 97% failure rate and thought, gee, that’s a really high failure rate. Is it really because we’re so bad at drug development? Or could there be some other explanation: like, maybe a lot of those genes associated with cancer actually have nothing to do with cancer? So they used CRISPR, everyone outside of bio’s new favourite bio trend, to systematically go through and re-test all of those drugs in cancer cells, but with the genes that they were supposed to be targeting knocked out. In the majority of cases, knocking out the gene didn’t change anything! Uh oh! So all of these drugs were still doing something; just not what we thought they were doing this whole time.

The study is so great because it’s so simple - “hey, let’s use modern tools to replicate all of this prior work, just testing some fundamental assumptions carefully” - and yet, these kinds of replication studies aren’t done nearly enough. Incidentally, by the way, the researchers stumbled upon a new, interesting mechanism of cancer-fighting that they’re now pursuing. If that’s not good science karma justice, I don’t know what is.

Speaking of science, here’s a classic paper from a few years ago:

One in five genetics papers contains errors thanks to Microsoft Excel | Jessica Boddy, Science

Apparently Microsoft Excel is particularly prone to misinterpreting and re-ordering lists of genes, because it interprets certain sequences of numbers as calendar dates. You can just hear the palms hitting faces in labs everywhere.

The fight for seed | Kate Clark, Techcrunch

The streaming wars: its models, surprises, and remaining opportunities | Matthew Ball, Redef

Great news from a Tesla-affiliated lab on the battery front:

And just for fun: an oral history of February 26, 2015, one of the greatest days in Internet history: it started with the runaway llamas, and ended with The Dress.

2/26: the day everyone came online for the internet’s perfect storm | Charlie Warzel, Buzzfeed

Have a great week,

Alex