What happens if building more housing doesn't work?

Snippets 2, Episode 6

I just spent the past week it the Bay Area, and it’s hard not to come away with an acute sense that there’s something wrong with the way that housing is working in the new economy: not just in San Francisco or on the peninsula, where it’s messed up for all kinds of local reasons, but really everywhere. This week I’m going to do some thinking out loud to see if I can make any sense out of three different threads I’ve been pulling on. This is by no means a complete assessment but it points to something I’m worrying about a bit.

Does building more urban housing actually help affordability?

In the 21st century economy, with its heavy emphasis on creative, professional, digital and financial work, much of our economic bounty gets concentrated in a select number of superstar cities: Both obvious ones like New York, SF and LA, and also smaller trendy ones like Denver, Austin, pick your favourite. To put it in Richard Florida Creative Class terms, any of these careers where your job is the creation of new forms of something - art, business, law, design, whatever - will benefit disproportionately from being around other people who are going similar things.

Understandably, there’s great demand to live in these cities: there are good jobs there, and they’re where you can find a certain kind of “good life” we’ll pay a premium for. In select superstar cities, you increasingly need a six-figure annual salary in order to make market rate rent, which most people don’t earn. So, many people are priced out of ever being able to afford a place to live unless they make some real sacrifice that they wouldn’t have to elsewhere: either living somewhere very small or with multiple roommates, or living very far away and enduring a multi-hour commute every day.

If there’s so much demand to live in these places, shouldn't the answer be increasing supply? The argument is pretty straightforward: if you build more housing, prices will come down. Makes sense! Anyone who’s spent any time in San Francisco will have heard this argument a whole lot: the answer to Bay Area unaffordability is to build more housing, and the biggest driver of local inequality and stagnating inequality are the local planning and zoning regulations that make it really hard to build more units anywhere.

The logic to this line of thinking is attractive, because not only does it make sense on paper, it also provides a convenient scapegoat for the source of all our problems: the NIMBYs. The “Not In My Backyard” set, as the acronym has popularized, has become a placeholder name for the general phenomenon of existing landowners who, whatever their motivations may be, move to protect their windfall gains in the housing market by obstructing new development that could lower housing prices.

However, the story gets a little murkier when you look at cities that have handled the NIMBYs, yet find that it doesn’t seem to make a difference. Where I live, in Toronto, is a pretty good example. Toronto is big and growing fast; it’s not quite New York level global megastar city but it’s one rung down, as North America’s fourth biggest city and a major financial centre. It also builds a lot of the specific kind of housing that has emerged in high demand recently: dense condos and apartments that are centrally located or close to transit, and cater to downtown knowledge workers that earn good salaries as an entry point to the housing market. They’re stacked vertically, so they don’t take up very much land, which eliminates the fixed supply of urban land as an unyielding constraint. This is the kind of housing that the free market advocates argue for: if this is what the market wants most, let them build it!

Now the question is: does mass-building this kind of housing actually move the needle on affordability? The anecdotal narrative around here certainly suggests otherwise, and recent data agrees. Condos are getting built in huge numbers; they all get bought immediately, and for the most part, they’re all lived in. But no matter how many units get added, they don’t seem to be driving the price down at all. It’s almost as if they’re drawing more and more money out of some sort of vast, hidden reservoir, and while it’s easy to blame foreign or investment buyers for this, or even Airbnb, that doesn’t really fit either. The majority of this newly built housing stock is being used for its intended purpose, which is local people living in it. But it’s not helping affordability, nor is it helping the increasing opportunity gap between creative professionals versus the rest. The market is supposed to fix this problem, but doesn’t appear to be doing so. Why, though?

Cities aren’t just where the jobs are; they’re where the other jobs are, too

One way that the labour market has changed over the last couple generations is that careers are now typically made up of a series of jobs at different organizations, away from the default of sticking with one or two for the long haul. Optionality - in the form of having lots of attractive jobs near you at any given point in time - is even more important today than it used to be. I honestly think this is the single biggest recent driver of why a select few large cities are disproportionally running away with the compounding gains of economic success recently: if you are a professional worker, those select cities aren’t just where the high salaries are, they’re where the highest number of other options of high salaries are. For a skilled professional, high rates of job turnover are a path for accelerated career advancement: it’s much easier to find a new job that will level you up and boost your income, and you already live in the city where they are.

At the other end of the labour market, increased job turnover generally works against you, not for you. For most of the “new blue collar” service industry jobs, the trend towards short labor stints (and, increasingly, to hiring contractors rather than full-time employees) will work in the opposite direction. The more dense the city you’re in, the more quickly you can be replaced, all other things being equal; so the fewer labor protections and wage gains you’ll be able to accumulate in any one place. Unions used to prevent this to some extent, but each year they get progressively replaced by more third-party service workers and 1099 contractors. The wage benefits that density used to grant you are increasingly offset by the loss of job permanence in a high-turnover world.

The net effect of these two trends is that cities do not offer the same kind of economic opportunity they used to. Living in a dense city used to increase your wage-earning potential in more or less the same way that getting a college education did; both were ideal, but either one was a significant factor on its own. Today, we see something else: having a college education, and being part of the specialized professional employment class, has become a prerequisite to being able to enjoy the wage-boosting effect that a city gives you. Density used to be a stepstool; now it’s a wedge.

Credit and condos as an investment

The third factor that somehow gets left out of a lot of armchair debates about housing and yet is an essential (possibly THE essential) element in all of this is credit.

Houses are big purchases, and we almost always buy them on credit and pay off the mortgage over time. Even if you have cash in hand, you will probably still opt for a mortgage: it's ultra cheap cost of capital, subsidized by the government. You should probably take it! Over the last century, in the United States and many (although not all!) western countries, we’ve entered and perpetuated a durable, positive feedback cycle where the supply of credit and the price of housing has mutually reinforced each other upwards.

Houses aren’t just a place we live anymore, they’ve been thoroughly financialized as a path to wealth creation. My wife and I bought a house last year, and it continually amazes me how much economic leverage has been productized and packaged up into “Homeownership”. Most homebuyers don’t really understand how powerful what they’ve signed is, nor how sophisticated the machinery is behind it in order to make it just work.

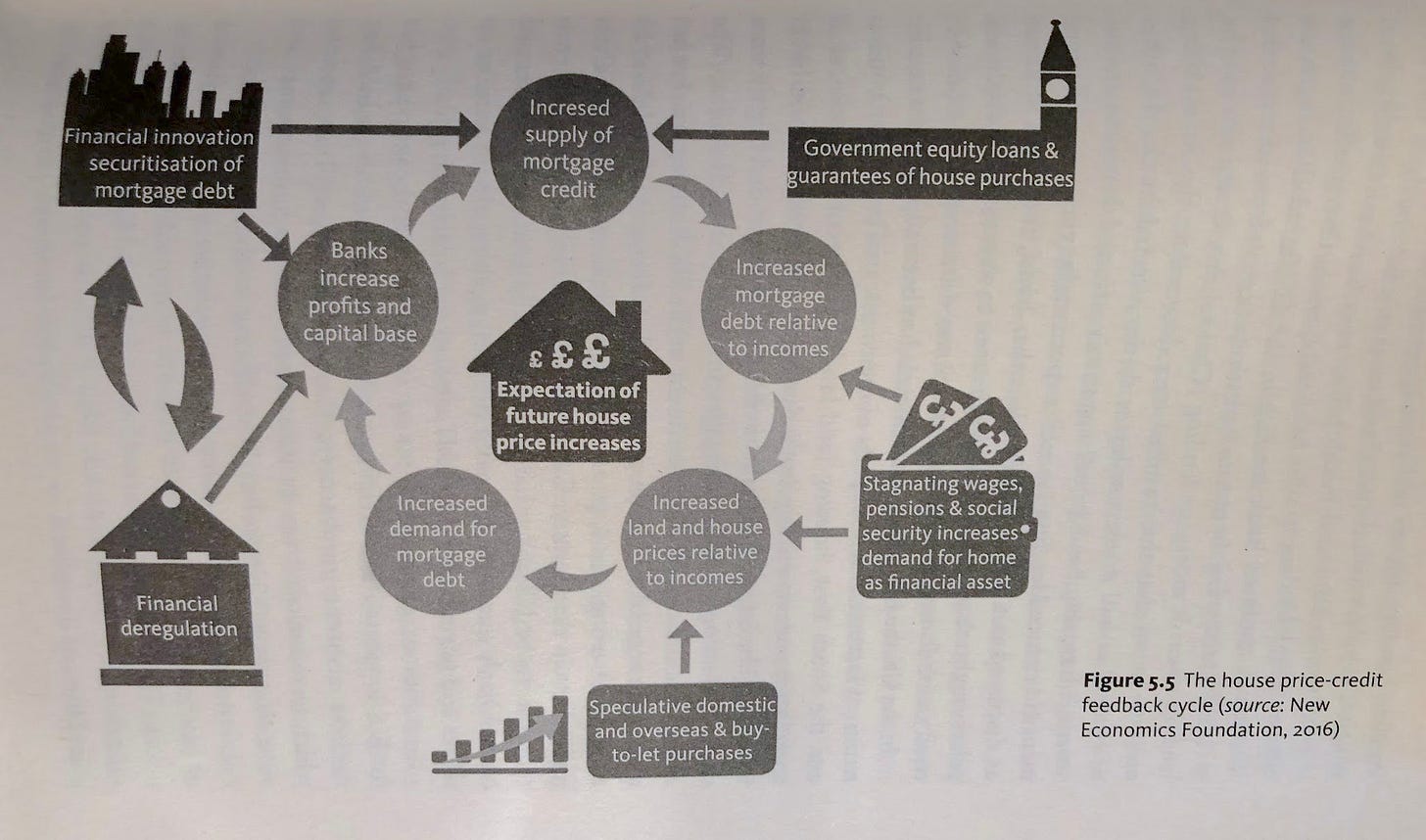

The thing with positive feedback cycles is that they necessarily come to an end, unless there is some enormous reservoir of resources they can draw from in order to keep perpetuating. In the housing market, the basic mechanic through which this keeps perpetuating is: banks lend money to homebuyers; the more freely they lend it, the higher it will drive house prices. This has two mutually reinforcing consequences: people will need bigger mortgages, and the bank will be able to issue them, since they’re allowed to lend up to a specific leverage ratio that is now buoyed by rising home values. There are many more ingredients to this cycle (see the diagram below), but that’s the basic idea.

From Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing, which I recommend to everyone.

So what does this have to do with our two earlier points about cities and job turnover?

When a young, educated professional moves to a big city, they instantly become richer, without even realizing it. How? Their income earning potential has gone up, as the options available to them to earn that income have multiplied. From an expected-future-earnings point of view, a young professional massively increases the present value of their future income just by moving to New York or Toronto or San Francisco, period.

Furthermore, many of these young professionals come from families that are financially comfortable enough for their parents to be able to assist with down payments if necessary. Had they stayed in Nashua or Cleveland, they might never have needed to tap this wealth; but moving to an expensive city to pursue a prestigious career is a pretty common prompt for people to ask parents for financial help. It's another important source of “creditworthiness” that may go overlooked when people think about urban inequality, but it’s a big one.

Anyway, these professionals then promptly spend that creditworthiness. They spend it on a mortgage (or on renting while they save up for a mortgage.) And if dense cities are genuinely increasing that young professional’s earning power and creditworthiness, what do we expect is going to happen? That increased future earning power is going to get capitalized in the form of higher prices on those condos and starter houses that these young professionals are buying. The high price is justifiable, though, because it’s not an expense, it’s an “investment”.

What this means is that we can effectively add a new contributing arrow to our diagram above: the act of moving to a city, just the act of doing it, increases your wealth if you’re an “above the wedge” professional. Your future earnings go up, because density works in your favour with increased job turnover. If someone is willing to lend to you, then you can turn those future earnings into present-day capital. And the housing market is how we do that.

Paradoxically, and here’s the bad part, this brings us to this absurd but understandable situation where increasing the supply of this very specific kind of housing actually makes their price go UP, not down. Building more of them means more room for more young professionals to move in, bringing in new options of creative class jobs, which in turn increases the net present wealth of the people who were already there, which (circularly) gets capitalized into the cost of all of the new condos that are going up.

Putting the three together:

If you put these three things together...

There is a particular kind of housing - condos - that has become this financial asset that’s absorbed and capitalized the network effect density gains of young professionals all moving in close to each other. It gets multiplied by accelerated job turnover: the more jobs you have in an average career, the stronger this network effect will be. For various reasons, condos has become one of the main levers we’re able to pull when we collectively decide to build more housing. What I’m worried about is the possibility that we’ve entered this feedback loop in which building more supply doesn’t really help affordability for anyone below the wedge. Each incrementally added condo makes all others “worth more” (assuming an ample supply of credit) by increasing the pool of creative class employees and job options, while doing nothing for affordability for anyone below the wedge.

The denser the city gets, the more bifurcated the job market becomes; the ready supply of credit that’s available means that any given unit that’s built is going to get priced not at what the local labor market can support, but rather what the “young professional creative/credit engine” can support, even if those young people moving in don’t have high incomes yet. The more young professionals there are that emerge out of the rest of the country and move into those homes, the greater their sum creditworthiness becomes: in a world of high job turnover, the presence of more young professionals makes you wealthier if you’re also a young professional (because it increases the pool of all your future jobs), but not otherwise; that wealth gets capitalized immediately into your condo price, and is happily financed for you by your bank.

My worry, and I hope I’m wrong here, is that on average, adding more housing units just makes this cycle spin faster. (Unless you could add SO MANY housing units that you could actually break through the wedge, that is. But that seems to me like it’d be hard to do! That would also be quite unpopular locally, as it would undermine an awful lot of locally built up wealth, and any move to do that is usually unviable politically.)

If anyone knows a lot about this or has strong opinions about it, please let me know, I’m always looking to learn more about this. If you find this stuff interesting, I recently recorded a podcast with Kim Mai Cutler, who actually knows a lot about housing, hosted by Erik Torenberg, which you can listen to here:

A deep dive on housing with Kim Mai Cutler and Alex Danco | Venture Stories

And a perma-link to this post is here:

What happens if building more housing doesn’t work? | alexdanco.com

Reading links for this week:

The most expensive lesson of my life: details of SIM port hack | Sean Coonce

Do you own any cryptocurrency? For that matter, do you use computers for anything at all? Read this if you do. It’s an excruciating story, and kudos for Sean for writing about this. Number one take home message here: two-factor authentication by SMS is not safe! Nor, for that matter, is any method of storing cryptocurrency actually safe except for storing your keys in a cold wallet.

Talk about second acts - Real Networks, home of the beloved love-to-hate media player we all used in the 90s, is apparently back, having used its massive media library to… train surveillance networks how to look at faces more effectively. Take it how you will, folks. CEO Rob Glaser is a real interesting guy though, and his interview episode of The Internet History Podcast is one of my favourites.

The ability to synthesize ammonia efficiently out of nitrogen gas and energy has been something we’ve wanted to do for a long time. The Haber-Bosch process, which produces the bulk of the world’s nitrogen fertilizer, works well at vast quantities but is energy intensive (it’s responsible for more than 1% of total planetary greenhouse gas production) and necessarily centralized. Local, variable rate ammonia production would be a great way to take advantage of surplus wind power at night, or solar power during the day, where excess kilowatt-hours can be put to useful work.

This is an old, classic must-read; if you haven’t read it, read it twice. It’s an important paper on the nature of information, property, ownership, and the age-old concept of whether you can truly own an idea, or merely just its expression - and what that means in an age of software. (I reread this recently as a part of a project I’ll be making a bigger announcement about soon. Stay tuned.

The startups building ‘dark kitchens’ for Uber Eats and Deliveroo | Financial Times

Fresh off of Cooking As A Service a few weeks ago, a fresh look by the FT at what’s going on behind the scenes at Cloud Kitchen and elsewhere.

Have a great week,

Alex