What a year it’s been. Last February, before joining Shopify, I wrote a post called Debt is Coming that provoked a great discussion around how fixed income is finally going to challenge the all-equity fundraising model in software startups. (It remains, by a long shot, the most widely read piece I’ve ever written.) Maybe 24 hours after posting it, I got an email from Harry saying, “Your timing is incredible: this is exactly the bet we’re making, and exactly what we’re building.” And so, we met.

Pipe officially launched a couple weeks later, and their momentum over the last year has been stunning. Here was a chat between Harry and I in July, that gives a little preview:

It’s not debt, it’s better: an interview with Harry Hurst of Pipe | July 2020, alexdanco.com

And that brings us to today.

Pipe’s big fundraising round yesterday (with Shopify enthusiastically participating) is the real beginning. For the time being we’re going to keep quiet about Shopify + Pipe specifically; today, I want to talk more generally about Pipe and Platforms. It’s a bigger deal than you think.

Equity Shares and the Black Box

When you buy equity in a startup, the asset that’s being exchanged is a black box. Investment goes in, something happens that you can’t quite know; and then later, profit comes out. Hopefully.

Equity shares are the atomic unit of value for growing these kinds of companies. Companies are made of people - founders, employees, investors - and their relative arrangement and motivation and ownership are all represented through the atomic unit of the equity share. When you’re funding a Black Box company, equity shares get you, your VCs, and your employees all aligned on the same unit of ownership, even if you don’t totally know what it is you own yet.

Getting investors, employees, and founders aligned on this atomic unit of value was an important step in learning how to grow startups. It helps you make a bet together: “This company could change the world in an unpredictable way. We don’t know how big it could be, or what the founders will do, or how much money this will make. So let’s focus on growing the size of the black box, rather than solving for what’s inside.”

Software is well-suited to this kind of black box investment, as the market for software turned out to be bigger than we thought by a couple orders of magnitude. So venture capital and tech employment co-evolved with software companies around the atomic unit of the equity share, into a familiar and efficient process.

As you know, this came with a catch. This model is tuned for a particular kind of bet, where you’re going after a grand slam or nothing. Pursuing anything less than a grand slam (multibillion dollar aggregator / platform opportunities) is insufficiently ambitious for the model to optimally work. I wrote in the Debt essay: Continuously selling equity, even at high valuations, is more expensive than the narrative suggests. It costs you optionality. The higher your equity valuation, the fewer out of all possible future trajectories for your business are acceptable.

There are some kinds of companies for which this is totally the right path to take. If you’re all-in on building a radically different future, and want to fund it entirely through printing equity shares, then you’re all set: the black box VC model is pretty optimized for you today.

But most businesses aren’t that. When you have customers you can serve profitably today, and you want to fund yourself off of the strength of something that exists today, the all-equity funding model is not optimized for you. You ought to ask: is there a complimentary way to fund your growth, that takes you on a different growth path?

The Opposite of the Black Box

Now, there’s an entirely different way that you can raise money to grow a company, and that’s debt. In contrast to VC or equity in general, when you loan money to a company, you do not want to think about it like a black box.

Debt serves a different purpose in the company’s capital stack than equity. It has lower cost of capital, and a tighter commitment. You’d like a claim on something as direct as possible; as close to the source of revenue as possible. You want the black box to be as small as possible.

In contrast to VC - where over the past 30 years of software, there’s been a circular “we shape our tools, and then they shape us” coevolution around how equity works - this hasn’t happened for debt yet. We haven’t figured out the right atomic unit; nor do we really understand the playing field where that atomic unit can live.

It’s funny that this hasn’t happened yet, because software can also be really interesting as a fixed income proposition. Recurring revenue is not only predictable, it’s also turned out to be lower-risk than people initially thought it was. Vista took an early claim to this idea, with their line, “Software contracts are better than first-lien debt.” When I was at Social Capital we looked an awful lot at businesses like Slack that knew their CAC/Payback math like clockwork, and it certainly seemed to us like Black Box Equity wasn’t the best way to keep funding growth.

But we had not yet figured out how to optimize debt for 21st century software businesses. Part of the problem is the structure of debt itself. Debt is a claim on the entire business; not on a smaller or more granular atomic unit. The recent fintech explosion has largely gone in the wrong direction here. To offer a more attractive cost of capital, lenders are exploring creative financing mechanisms like Whole Business Securitization, which isn’t real progress - it’s just a more severe, and more easily executable, claim on the entire business as a black box.

What we should be doing instead is trying to shrink the black box down to something smaller. Then we can define the tradable atomic unit we can sell to fund the business, and figure out the playing field where it will live.

Pipe and Platforms

You already know that I’m writing this about Pipe, so there’s no surprise to spoil here: Pipe figured it out.

Pipe starts with a simple idea: shrink the black box. If you have real revenue and real cash flow coming in, and you want to grow your business by pulling that revenue forward, don’t sell debt, or a WBS; don’t sell a claim on the black box of your entire business. Sell the smallest unit possible. Sell the thing itself: your revenue. And the purest way to represent that - the atomic, tradable unit of the subscription economy - is the revenue contract.

This is the first step of the Pipe thesis: the revenue contract is the atomic unit. It’s the closest thing there is to revenue itself, and the smallest possible black box you can trade. (Although this is a topic for another time: yes, they have the accounting figured out. It’s clean, and elegant. Ask Harry; or even better, ask their customers.)

Once you have an atomic unit you can trade, it’s clear what to do next: create a market for it, with a buy side and a sell side. Companies can sell their recurring revenue streams for cash up front, investors get attractive fixed income return; and best of all, it’s a market, so there’s always a fair price.

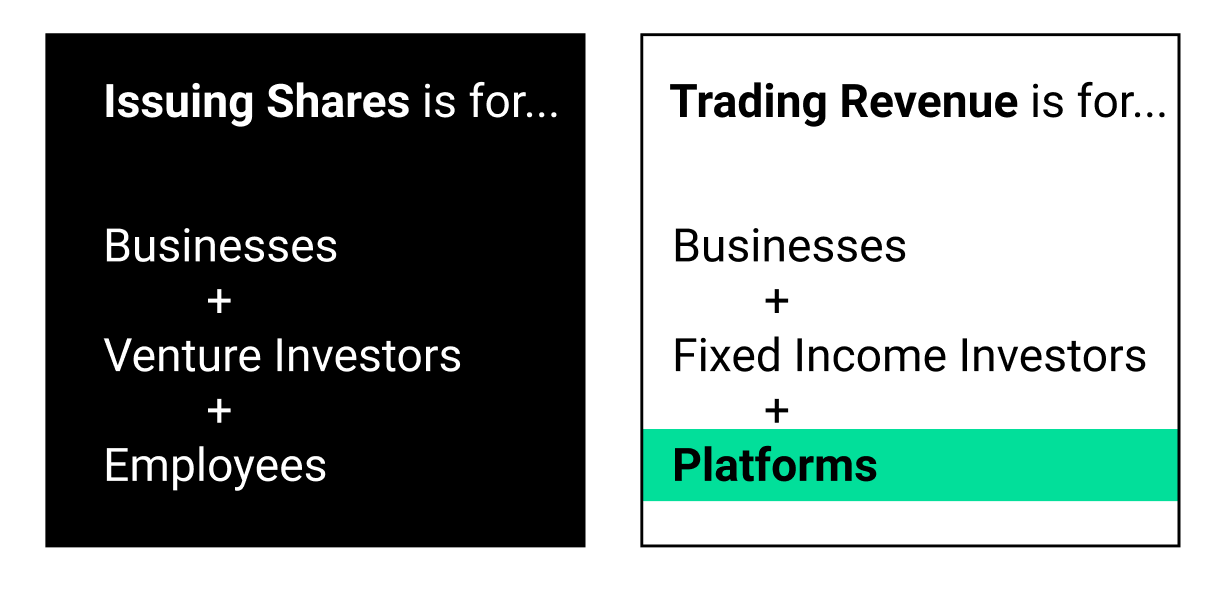

It looks like factoring, it looks like debt, but it isn’t any of those things. It’s a new tradeable asset class with revenue contracts as the atomic unit. Businesses have been waiting for this for a long time. We’ve already maxed out the first lever you can pull to fund growth: issuing equity shares, off of the promise of what could be. Now, Pipe is introducing the second lever: which is selling revenue contracts, off of the strength of what you’ve already done.

Now, remember something important about why equity funding works so well today: it isn’t only as a vehicle between investors and the business. It’s because equity shares bring in a third critical group - your employees - and directly aligns them with success. So who is that third player, for trading revenue?

It’s the platforms.

The critical moment for me, when I really had that flash of seeing what Pipe makes possible, was realizing what this means for platforms.

Platforms are the Production Capital of the internet age. We’re still in the early days of internet platform businesses - including Shopify, but also think Salesforce, Microsoft, Okta, Stripe, Plaid, you name it - creating this incredibly rich and almost “self-serve” environment where small startups can gain access to powerful embedded tools and services. These platforms have great vested interest in helping their customers succeed, and they also have cash they can put to work. This should be an ideal win-win situation.

But equity investment is the wrong tool to do that. For one, it creates huge signaling risk for the business; moreover, these platforms need that investment to be relatively liquid. They don’t want it tied up for years in their customers’ equity.

Meanwhile, the presence of the platforms themselves lowers some risk and uncertainty inherent to their customers’ business. From day one, founders can stand on the shoulders of giants more easily and affordably than at any point ever before. We are really only at the beginning of understanding how pay-per-use API services and platforms are going to change the business models and financing structures of the companies who use them. And who better to co-invest into this transformation than the platforms themselves?

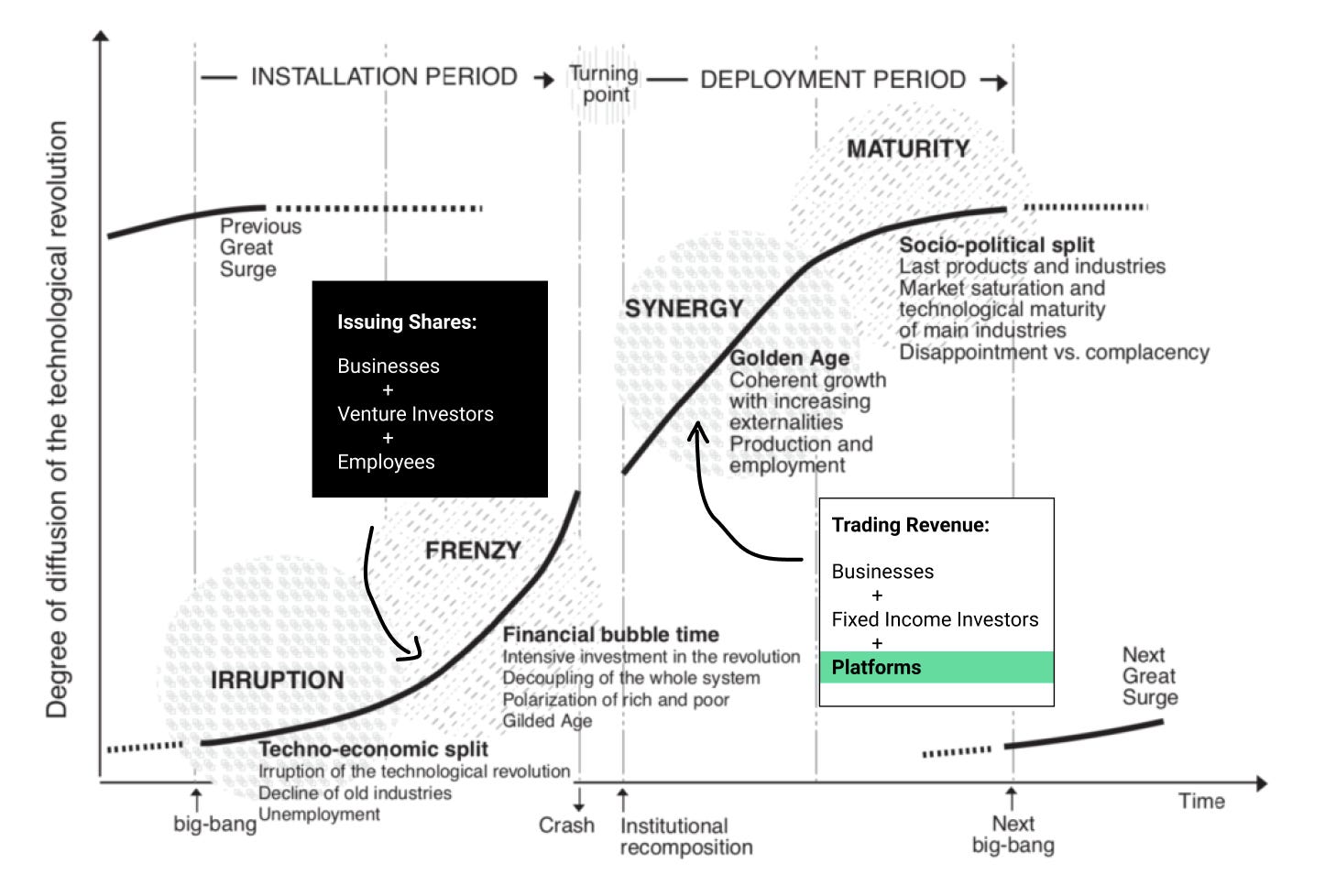

Over the past 20 years we saw this fruitful co-evolution between startups, VCs and employee equity programs, which aligned around equity shares as the tradable atomic unit. We’re going to see the same thing happen this decade between startups, fixed income investors, and platforms, with revenue contracts as another tradeable atomic unit.

This will become normal quickly. You know how today, it’s totally normal and expected for some percentage of employee compensation to be invested back into the startup, in the form of equity grants? Before long, it’ll be totally normal and expected for some percentage of platform revenue to be reinvested back into the startup.

And you know what’s so great about having two levers you can pull, instead of one? They can work together. Pipe isn’t competitive with Venture Capital! They both strengthen each other. Being able to trade revenue with investors and platforms means you can raise less equity, and take less dilution down the road. And having a strong equity base means you can access that lower-cost capital, and add a bit of leverage by trading revenue, with focus and confidence.

What’s especially exciting to me about this new financing path for high-growth businesses is that it creates so many more paths to success than the all-equity model offers you. There are so many amazing companies out there, growing fast and making customers happy, that honestly are not billion dollar opportunities -but are great businesses you can make great money financing.

In the original Debt piece, I asked whether we have begun the beginning of a great Deployment Period of internet businesses - and if we are, whether we’ve found financial alignment between funders and platforms. Pipe definitively argues that we have.

Our signature financing accomplishment of the “Installation Period” of software and the internet was finding that three-player alignment between startups, venture investors, and employees. We explicitly decoupled investment from production: we mastered the art of the black box. Our signature financing accomplishment for the upcoming Deployment Period of software will be The Great Recoupling between financial and production capital: finding a complimentary three-player alignment between the startups, platforms, and yield investors. We can see it.

The Golden Age is opening. It’s about to get so awesome. So for businesses everywhere: Got revenue? Pipe it.

Permalink to this post is here: Pipe it! Platforms, Funding and the Future | alexdanco.com

Before we go, this week’s Tweet of the Week is actually from two whole weeks ago, but Casey’s reply to my honest inquiry has been living rent-free in my head this entire time:

(In the end I went with Ish, obviously. So far it’s as good as hoped.)

Have a great week,

Alex