My weekly newsletter, formerly known as Snippets, has a new name! For news on the name-change, the newsletter brand, and a few other important items, head here if you haven’t seen it already.

If Netflix is a genius aggregator with all the subscribers, the best data, and the most focus on long-term compounding… then what’s the deal with this ransom payment they just made?

Today we’re going to talk about why even Netflix, a poster child of doing things right in the new internet economy, can’t escape positional scarcity and its cruel cousin, the Red Queen’s Race.

I’ve written about the phenomenon of abundance a bunch recently, including recent posts on gaming and cooking-as-a-service, because it’s one of my favourite topics that’s central to everything we do in tech and yet gets oddly little direct attention.

Most of the time when we talk about abundance, it’s assumed we’re talking about abundance of supply: some resource, product or service going from scarce to plentiful. But I’ve always believed that you get more insight out of treating abundance as a demand-side phenomenon: something that comes first, and foremost, from consumer behaviour.

What really gets abundance flywheels going is when consumer demand – specifically demand for more variety than can be produced by traditional producers – pulls production into getting “platformized”. When we look back at how technological abundance progresses, we often get really fixated on the emergence as new production platforms while forgetting why we wanted them in the first place – not demand for quantity or performance, but really demand for more variety.

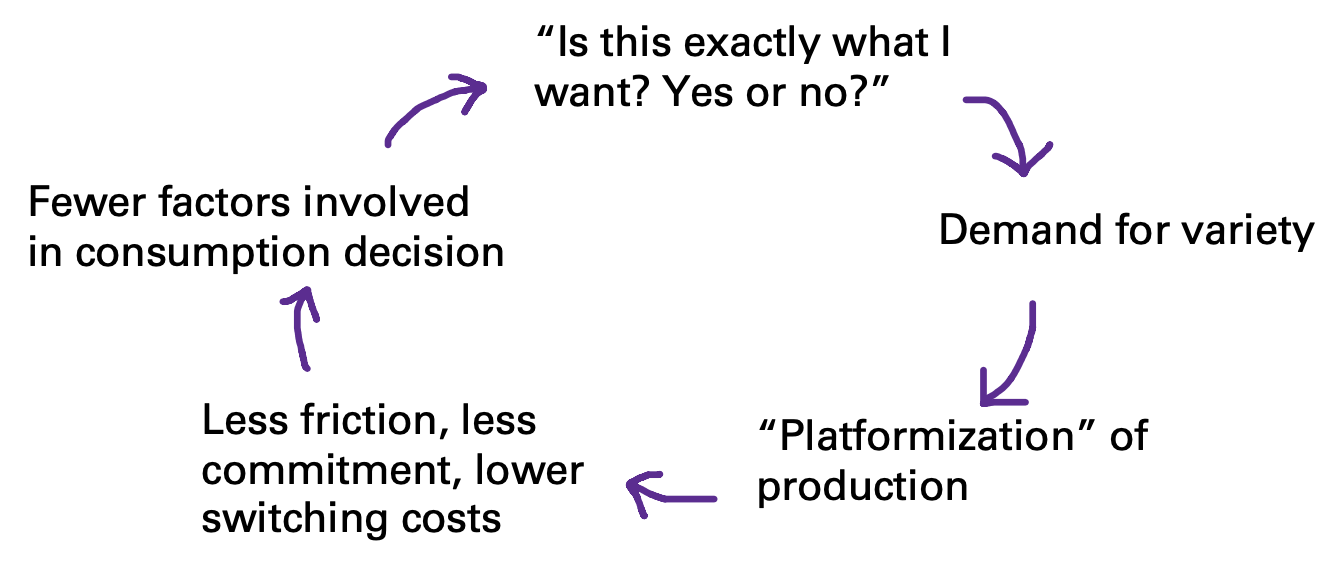

The signature behaviour that spurs on abundance is browsing. Consumers flipping through a Sears Roebuck catalog in the late 1800s, or surfing Netscape Navigator or the App Store a century later, are all engaging in the same thing: demanding a kind of specificity, variety, and low-commitment shopping that fuel demand for general-purpose production and distribution platforms. As platforms grow, they make this kind of frictionless consumption easier, spinning the abundance flywheel more. Variety, not volume, is what really fuels the abundance cycle.

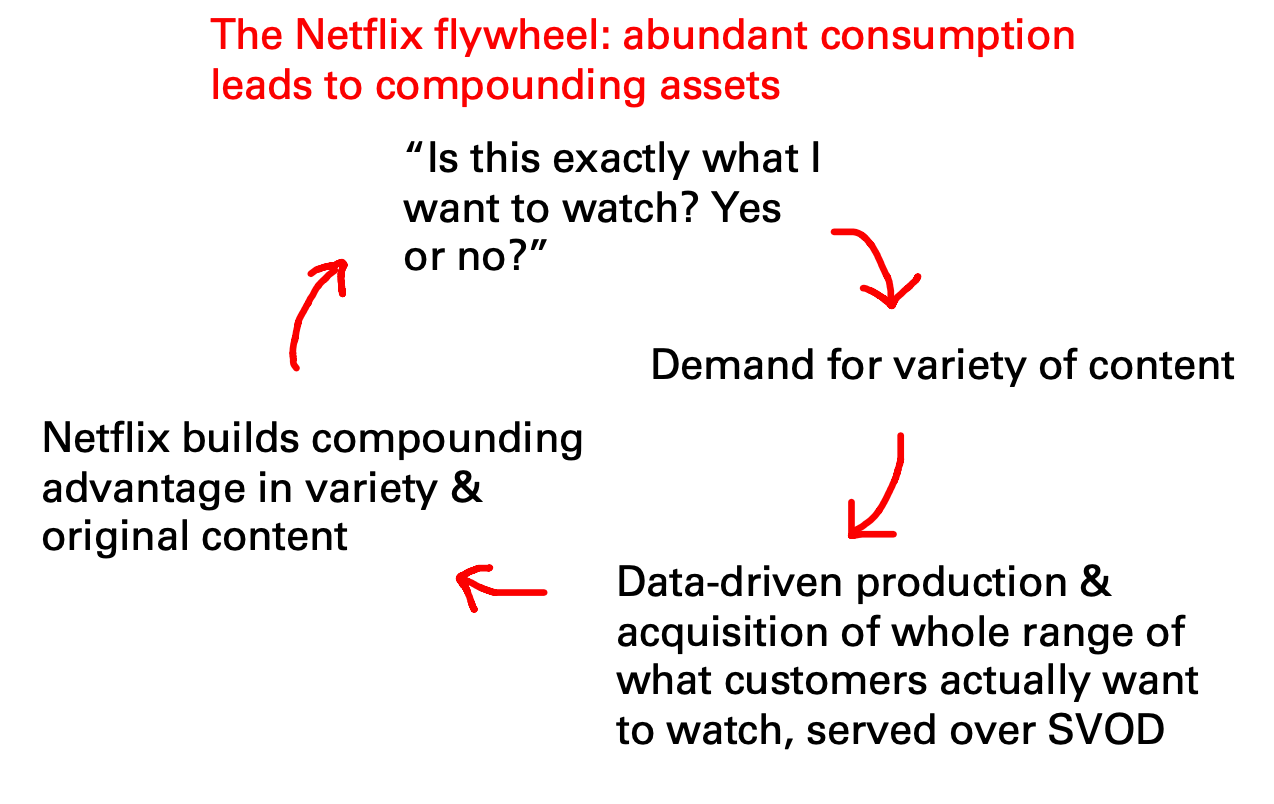

The recent rise of Streaming Video On Demand (Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, Prime Video; generally “SVOD”) as the latest form factor for mass video consumption illustrates a few of these principles. When the internet ushered in this new friction-free way to consume video, the change in our behaviour wasn’t striking in that we consumed more video (we were already watching plenty of TV) but rather the increased ease through which we could watch a variety of video, and find exactly what we want, whenever we want it.

One of the big questions for SVOD, accordingly, is how content producers and owners are going to adapt to this new era of low friction and easy access to variety. You can imagine a basic abundance cycle for streaming video looking something like this:

This brings us to Netflix. All of their hard work and execution to date has put Netflix in an enviable position: a frontrunner in the race to remake TV and movies. Netflix’s early success, both in mail-order DVDs and then in streaming video, came by putting a new distribution model on existing content that it rented on the cheap from legacy media companies who didn’t yet understand the new playing field. As a temporary business model it worked great, but now the free ride is over. Goodbye cents-on-the-dollar deals for hit shows; hello having to bid for content against deep-pocketed SVOD challengers, many of whom own huge back catalogs that they now understand how to use.

But even without these sweetheart content deals, Netflix still has a path to long-term dominance. They have three valuable things: 1) a lot of subscribers, 2) the ability to access lots of capital, and 3) a lot of “ground truth” viewing data for how to put that capital to work.

Netflix’s opportunity is to ride the abundance flywheel before everyone else, building a moat out of variety along the way. That means a mountain of original content and smart acquisitions that it can lock up for the long run, cultivating a long tail of everything-under-the-sun that no one else can match. The high fixed costs of producing original content pay off as zero-marginal cost streaming goods that Netflix can offer forever. And now that Netflix has successfully aggregated all of us as viewers, it ought to know how to spend that money in a way that handily out-earns their cost of capital in the long run.

But the folks at Netflix have run the numbers and concluded that it’s more important for them to rent Seinfeld for five years – after which they’ll be left with nothing – than to develop 600 million dollars worth of new shows and movies that they get to own forever.

Ouch.

Remember when we talked the other day about how in environments of abundance, your relative position in line becomes increasingly important? That’s exactly what’s happening here. Netflix has likely read the room and concluded that most consumers are probably going to pay for 2 or 3 streaming services and no more. So Netflix’s place in line in customer preference relative to Disney+, Hulu, HBO Max, Prime Video, Apple TV+, Peacock, etc is the most important thing for them to secure right now.

Unfortunately for Netflix, the breadth and variety that used to define Netflix’s signature value proposition as the “abundant streaming service” isn’t a differentiator anymore. It’s turned into table stakes in the battle for eyeballs; everybody has a mountain of content to bring to the table.

So Netflix has to find something that is a differentiator: one of the few superstar TV shows with enough brand power to headline Netflix’s roster, and attract and retain subscriptions on its muscle alone. Friends is one of those TV shows. The Office is one of those TV shows. Netflix had them, but it lost them both. So they had no choice but to go find a new one.

Netflix coughing up $120 million a year for Seinfeld is a great example of something called Wholesale Transfer Pricing Power. Normally, we expect that whoever owns the customer relationship is going to have pricing power over those who don’t. But there’s an important exception, which is when the producer has a strong enough brand or a scarce enough product to overpower the distributor and set their own price. Publishers have leverage over most of the authors they carry, but not over J.K. Rowling. She can set any price she wants.

Wholesale Transfer Pricing Power becomes especially important in environments of abundance and emerging positional scarcity. If many different aggregator consumer companies are all racing each other for make-or-break market share, and if you need an ace in your hand today, you’ll have to pay for it at the expense of your ability to develop and own future hit shows. But an ace in the hand beats four in the deck, so you go get Seinfeld.

The cruel thing about an environment of abundance is that the more cards there are in the deck, the more the aces matter. In the old days of scarce linear TV programming, it mattered who had the hit shows. As Netflix introduced a new form of abundant on-demand consumption, they found a new element of performance where they could excel: their variety was what counted in attracting consumer eyeballs. “Browse our massive selection, any time” was a great value proposition for starting the abundance flywheel and growing the market.

But now that on-demand variety is table stakes, the hit TV shows matter again, even more than they did before. The fate of these streaming services is going to come down to whether they’re able to grab a coveted spot in the top 2-3 positions. It used to be that a marquee show like Seinfeld had to carry a network through a prime time spot; now the success of the entire catalog is resting on how many families are going to go with the streaming service with Seinfeld versus the one with Marvel.

Unfortunately for Netflix, raiding their original content budget in order to rent Seinfeld for five years is a bit like a University starving their academic faculty in order to buy the football team a few more wins. In terms of jacking up your relative ranking in the present, it does work. But mortgaging your long-term capability to create future hits (that you actually own) means leaving yourself dependent on paying ransom for each year’s big free agent show – eventually, it becomes the only working lever you have.

It gets worse when you remember that the switching costs between one SVOD service and another aren’t that high. Netflix has good customer retention so far, but it hasn’t really been challenged yet. When enough customers get into a “what have you done for me lately” mindset, SVOD providers will find they have to continually re-acquire their own customers in order to keep their heads above water. That means landing the rights to whatever marquee show is available in free agency, at whatever the price – because so much is riding on having a good name as your headliner.

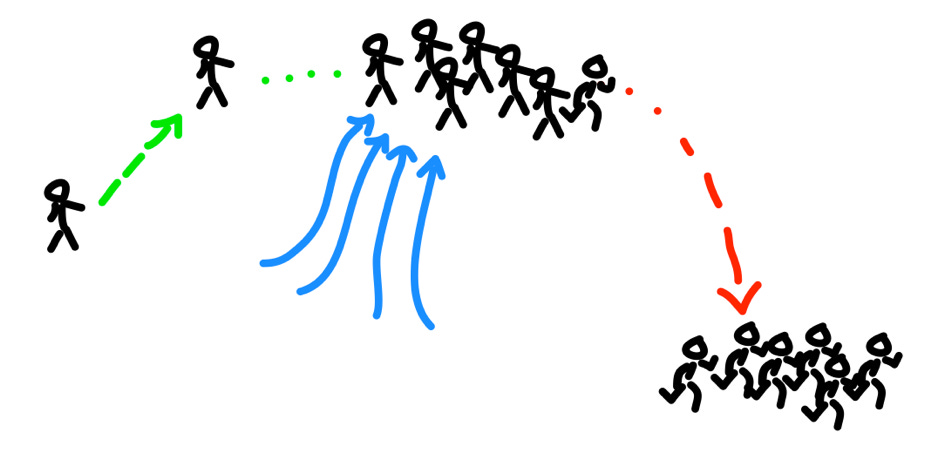

What’s happening is a kind of Red Queen’s Race: a cruel form of competition where the harder you try to outrun your competitors, the faster the treadmill adjusts underneath you. Over time no one accumulates any advantage, but everyone accumulates cost. Warren Buffett once described the phenomenon as like spectators watching a parade. When one person stands on their toes, they temporarily gain an advantage. But then other people copy them, and soon everyone is stuck standing on their toes. Every spectator is now worse off than if no one had ever made the first move; but someone always will.

There are examples of the Red Queen’s Race everywhere you look in tech. Some of them are explicitly positional scarcity: when you need to line up to access your customers, and you have to pay tax to whoever runs the line. That’s like Google and Facebook making a killing off of the boom in startup VC funding: they can simply force all the startups to bid against each other for ads, and sell more and more of their equity in order for their paid acquisition to work.

The kind of positional scarcity we see in SVOD is a little subtler, but it’s still the same thing. The “standing-on-your-toes” cost that gets higher every year isn’t paying rent to one gatekeeper, like it is for Google, but something more like free agency in sports. In any given pro sports league, the higher the level of average competition and the tighter the difference in skill and execution becomes between teams, the higher a ransom payment you’re going to have to make for those select few people who can generate a few extra wins on their own star power.

Contracts like Bryce Harper’s $300 million deal with Philadelphia are like the Seinfeld deal: the return on your investment almost surely gets worse on average as you pursue elite free agents, but you don’t have a choice. What matters is: can you make it into the postseason? If you can clear that threshold, the economic calculus completely resets; you probably make your money back. If not, you probably don’t.

At the end of the day the number one thing that matters for Netflix and Disney+ and all the other SVOD services is making it to the playoffs: the top 2-3 slots in consumer preference ranking for SVOD. Are you in, or are you out?

Competing on variety and homegrown content, like Netflix has done so successfully in their ascendance, was a great thing for kickstarting the abundance ecosystem and growing the whole market: every dollar spent actually meant better product and happier customers. But your place in line, at the end of the day, is a zero-sum competition. And in zero-sum competitions, the way you win is by getting zero-sum items.

Would the Phillies be in better shape as an organization long-term if they’d spend that $300 million (or even a quarter of that!) on their scouting and minor-league programs, homegrown talent development, coaching and analytics? Look, I’m not a baseball GM, but probably. Does that get you into the playoffs this year, though? Nope. Does it sell tickets this year? Nope. So you sign him.

Similarly, this treadmill of escalating headliner payments makes SVOD offerings a worse product for consumers than they could be. That $600 million could have gone into making more smash hits like Stranger Things and niche gems like Russian Doll that viewers love and Netflix can own forever. More importantly, that $600 million would have gone into an even bigger fight where everyone in SVOD stands to lose: the battle for overall time and attention that they’re losing to YouTube, Instagram and Fortnite.

But instead, it’s going to these guys:

Now, all of this sounds as if it’s a bearish sign for Netflix. But here’s the thing: this kind of Red Queen’s Race punishes everybody in SVOD. And seeing as Netflix is in the pole position, it may not mind having to sweat it out.

The funny thing about the position where Netflix is in is: since it’s currently in the SVOD lead, they paradoxically want as many competitors and as hard a competition in SVOD as possible. The Red Queen punishes everybody. The worst thing for Netflix right now would be two or three really fearsome competitors and no one else. But instead, they’re going to face off with like, eight to ten different services, all of whom are going to have to bid each other up on kingmaker content in order to get their feet in the door.

The more intense the competition for premium content heats up, and the higher the ransom payments get for renting Seinfeld or Friends for a few years, the more punishing the curve will get between winning and losing in SVOD. It helps resolve winners, but it also comes at the expense of creating anything new with that money. $600 million dollars could’ve funded a lot of great new stuff, sadly.

Competition is weird sometimes. We’re usually supposed to assume that more competition is better for the consumer in general; I mean, what could go wrong with companies having to compete against each other over who can offer the best product? But in this particular Red Queen’s Race situation, and in others like it, we have a funny outcome: more competition in SVOD means Netflix becomes a worse product than it could be, but builds a stronger moat and a better business than perhaps it deserves. Sometimes abundance flips things around like that.

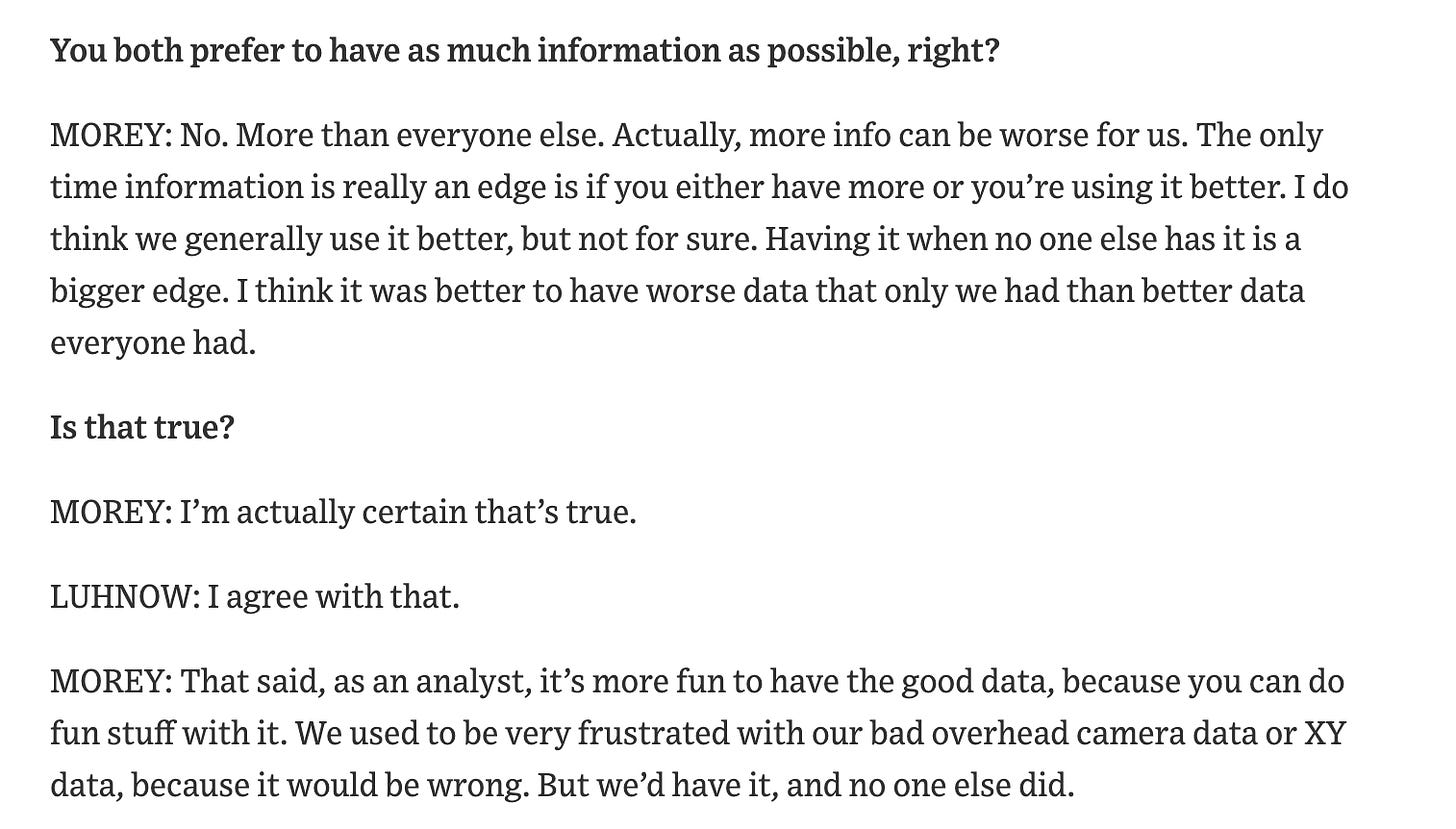

For any sports fans, investors, or anyone trying to gain an edge under uncertain conditions, this is a great piece:

I especially enjoyed this bit, where Morey articulates a pretty obvious but often ignored distinction: between trying to build a data edge that’s relative to your competitors, versus pursuing more data in an absolute sense, period. We often think we’re doing the first one but actually doing the second.

You may have heard that Google’s quantum computing team supposedly reached something called “Quantum Supremacy” recently. It’s a scary-sounding name, and to be honest it’s a bit of a scary topic: does that mean that “no code is uncrackable now”, as Andrew Yang tweeted out? Or is it a giant nothing burger? Here’s a very helpful FAQ from one of the few people who truly knows what they’re talking about here, Scott Aaronson, that I found valuable:

Scott’s Supreme Quantum Supremacy FAQ | Scott Aaronson

Here’s a good thread on Blue Apron’s unit economics not working out:

What happened to Blue Apron and what can we learn? | Adam Keesling

Did you know: the critically acclaimed genius show Fleabag and its creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge recently took home a bunch of Emmys the other day, before announcing a new huge deal between her and Amazon’s film studio. Here’s something I didn’t know: Fleabag started as a Kickstarter! It raised around $5000 to help start Waller-Bridge’s one-woman show in Edinburgh.

Oh and finally, a huge thank you and high five to everyone who emailed me tweets and articles and other hilarious examples of people in tech working overtime to make sure we all understand that WeWork isn’t a Silicon Valley company, okay? They’re From New York! We have nothing to do with this and we’ve always thought this was a scam, actually! You’re all the greatest.

Have a great start to fall,

Alex