Innovation takes magic, and that magic is gift culture

Silicon Valley's great trick: recasting well-worn business procedures as moments of gift exchange

There’s a certain magical quality to creating new things together. Any time we bring something genuinely new to life, especially if it took a group effort, something special happened that transcended rational behaviour or cost-benefit analysis. These new creations aren’t just accomplishments; they’re gifts.

The world of startups and innovation is full of this magic; clear as day for anyone who wants to look. Building new things is hard; not only because of each unit of effort it takes (which is lots), but also from the coordination tax associated with making something undefined. At every level of the game, from the details of product-building to fundraising, it is always going to be hard to coordinate groups of people to create something of unknown value, while asking for an unknown quantity of effort. This is the hard part of the innovation economy, and always has been.

Over the years of watching different parts of this world at work, I’m increasingly convinced that the innovation economy requires some sort of magic to actually work, and that magic is gift culture. Gift culture - which I’ll define loosely here as, “the social traditions within a community around gift exchange and reciprocity” - is load-bearing for creative builders, not just for feel-good reasons. Gift exchange does real economic work by elegantly solving coordination problems that would otherwise be prohibitively challenging.

If you’ve read this newsletter for a while, you’ll recognize that “gift culture helps solve coordination problems” is one of my favourite ideas to work into other stories:

The social subsidy of angel investing | November 2019

Social Capital in Silicon Valley | January 2020

VCs should play bridge | February 2020

Why the Canadian Tech Scene doesn’t work | January 2021

In this post I want to make some progress on the base idea.

One of the gems of the “Silicon Valley Tech Scene” (it’s a mindset, not a place; but the place sure helps) is the hidden social structure we’ve built that coordinates all of its different players to achieve what’s impossible through rational analysis alone. There are certainly other “non-cost-benefit” contributors as well: read Bill Janeway for the best writing on the three-player game of government, financial capital, and company builders; or Joel Spolsky on the transcendent motivation of engineers practicing a craft. But those don’t diminish the remarkable social feat that Silicon Valley has achieved in its building and fundraising culture, which works so durably, and yet is so hard to replicate from scratch.

The specific magic trick we’ve learned how to do is redefining well-worn procedures of the business world - from fundraising to project management - as moments of gift exchange. Startup fundraising, particularly at early stage, can intuitively feel like: “I’m gifting you capital, and in exchange, you’re gifting me shares.” The end result is an equity transaction, but the spirit of the deal is intuitively understood as a carefully measured exchange of gifts. Meanwhile inside of companies, the most important builder’s ritual to align and coordinate work - Demo Day - is again best understood as a gift exchange. “Everybody brings gifts to share at demo day” yields the outcome of aligning and coordinating work, but through a process that’s better understood as gift-giving.

And I’ll bet that, as AI creates so many more fleshed-out ideas at the top of funnel, gift culture will become even more important for exploring and homesteading the innovation frontier.

So, how does this all work?

Firms, Lemons, Cathedrals and Bazaars

To understand the economic magic of gift exchange, we’re going to call on two pieces of conventional economic wisdom: Coase’s Theory of the Firm, and Akerlof’s Market for Lemons problem.

Ronald Coase’s 1937 The Nature of the Firm gave us an compact way to think about what kinds of economic work tend to naturally contract between companies (exchange of goods and services at market prices), versus what kind of work tends to happen within companies. Traditional economics, which loves markets as solutions to any kind of problem, runs up against some classic challenges around coordinating work: the cost of searching for information and communicating with vendors, the cost of bargaining, the risk of losing company secrets, all contribute to doing some work in-house. Overall, Coase gives us a catchall way to think about how the friction associated with a complex transaction will dictate how and where that transaction naturally happens.

Meanwhile, George Akerlof’s 1970 paper, “The Market for Lemons: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism” uses the familiar example of a used car lot to illustrate the problem of repeat games with information asymmetry. In most of the interesting transactions in life, there’s an information mismatch between different parties in a deal: in his example, the seller of a used car knows whether the car is a ‘lemon’ (a clunker) or not, and therefore has a better sense of fair price than the buyer does - who may only know the average value for such a car. His paper articulates why “Bad quality drives out the good”, and why markets become more pessimistic over time about the potential of things.

These two ideas apply in situations where, like a startup out fundraising, we need to make deals and allocate resources around uncertain projects. At the outset, financing a startup means committing to an as-yet-unknown number of fundraises, at as-yet-unknown valuations, before obtaining line of sight to any financial returns. The Market for Lemons paper articulates the nature of the friction (and reputational risk) facing entrepreneurs pitching projects; Coase shows us why non-market mechanisms might have real advantages in coordinating such an exchange. But if not inside large already-resourced firms (who have their own problems with innovating), then where?

Enter Open Source software, a fascinating third alternative to Coase. Open source software demonstrated how Gift Cultures could be a powerful alternative to both companies and markets for building and maintaining complex products. It also gave us some great writing on gift exchange, notably Eric S. Raymond’s The Cathedral and the Bazaar, Homesteading the Noosphere, and other essays that explored the intricate social systems of the early web. In this world of digital abundance where the cost of copying bits was zero, status didn’t come from what you had, but from what you gave away, and the reputation you earned over time from playing repeat cooperative games.

The fascinating thing about open source (formerly “free software”, a much better name) is that it doesn’t just produce a free option for software staples; it often produces the best option in its category; sometimes shockingly better than any paid alternative. The question is, how can a bunch of people on a mailing list giving gifts to each other produce not only high-quality contributions, but high-quality synthesis of individual output into large-scale open source masterpieces? This is the interesting part. You can picture a community of dedicated nerds who take great pride in their craft, and great joy in repeatedly giving gifts to others, as a stable equilibrium. But the more interesting question is why it works collaboratively. What makes the sum greater than the individual parts?

Gift exchange increases communication bandwidth

I think the key to the answer involves the meaning of gifts, and the reputation of gift-givers taking creative risks. Real innovation requires repeated risk-taking, and trying many things that don’t work. Meanwhile, efficient markets discourage people from showing their whole hand, and taking big creative risks, when unsuccessful attempts are interpreted as “lemons.” The trope of the travelling salesman constantly plying new ideas is that after two or three attempts, you either get the door slammed in your face, or move to a new city. Inside of companies, which should be more hospitable to risk-taking, aren’t actually in reality; for the same reasons. If anything, reputation matters more inside of firms than anywhere else - so real, repeated risk-taking is rare.

But all of this changes if everyone agrees that we are in a gift-giving situation. Gift exchange flip the Lemon Market problem upside down, because of the particular social rules around gift-giving and celebrating intent. Gift culture has sacred protocol: if you’re offered a gift, you must accept the gift, and you must reciprocate either in return or by paying it forward. If I offer you a gift, saying, “Here is all this information, promise and potential”, then by the rules of gift exchange, you are obligated to take it seriously, and you are obligated to offer some potential in return, for a window of time.

This frees (actually, compels) everybody in the gift exchange to embrace a measure of creative risk that, in normal circumstances, would signal “I am crazy”. There is a window of time in which different social rules apply, in which you have lots more room to move. You have until that window closes to “figure out what you have here”, at which point the gift exchange concludes, and normal economics reassert themselves. At that point, the deal or plan proposed goes through a conventional assessment of merit. And often it doesn’t pass, but sometimes it does, at way higher levels of ambition than would normally materialize. And that, my friends, is kind of magical. The gift exchange did real work; just like an enzyme does real work catalyzing a reaction.

The best way I can describe the nature of the work done is as information transfer. I have a hunch that gift exchange is actually a higher bandwidth channel for information sharing than market exchange. The giver can assign all sorts of meaning to a gift about its purpose, how it was made, and what they love about it, and the recipient will actually receive that message with much higher fidelity than in other sorts of transactions. That’s Information Theory 101: information isn’t what you say, it’s what they hear. The reciprocal rules of gift exchange compels you to actually hear what other people are telling you about their intent and purpose; which is the single most important bottleneck of creative collaboration. When given a high-bandwidth communication channel for “figuring out what we’ve got here”, we gain a window of opportunity to imagine. For a moment in time, the market for lemons problem is inverted: we are only interested in what could go right. We are blessed with potential.

Gift Capital

So far we’ve been talking about metaphorical gift exchange, but let’s shift gears for a minute and talk about literal gift capital.

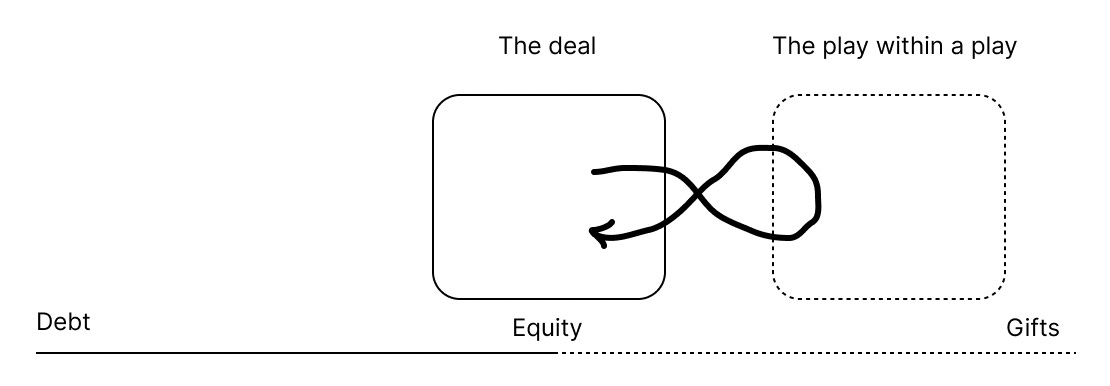

We’re all familiar with the two basic ways you can finance something; debt and equity. But it’s worth thinking through where gifts fit on that spectrum. Probably like this:

It’s worth remembering that literal gift capital often plays an irreplaceable role in getting new projects off the ground! It’s funny how gifted seed capital has become kind of taboo in today’s climate; it hits every check box of privilege, luck, unfairness, what have you. But it’s frequently there.

What kind of rights, or claims, does gift capital have? If debt gives the issuer a senior claim on the success of a project, and equity gives you a residual claim, then gifts give you something else: a social claim on the success of a project. That social claim has obvious appeal, and you see it clearly at work in ventures like restaurants, art galleries, show business; where it’s clearly about the social cachet and returns to being able to close a business deal over a meal at your place.

I wrote The Social Subsidy of Angel Investing five years ago about this significant “lift” that this social benefit plays in making Angel Investing in tech startups a worthwhile undertaking:

From the outside, angel investing may look like it’s motivated simply by money. But there’s more to it than that. To insiders, it’s more about your role and reputation within the community than it is about the money. The real motivator isn’t greed, it’s social standing – just like a century ago, with the original Angels who financed Broadway shows. Angel investing is how you stay relevant. It’s how you keep getting invited to things. It’s how you matter. Angel investing isn’t about getting something, it’s about being someone. …

In an environment like this, angel investments are the ultimate flex. They’re the universally permissible bragging format: half “I saw this potential when none of you did” and half “I was invited to this deal and none of you were.” I don’t mean to say here that all angel investment is social posturing – some angel investors are among the kindest, most humble and helpful people I know. But the social returns to angel investment aren’t just a happy side effect. They’re often the main thing people are really after.

It’s also convenient that the investment return profile of angel investing for social status is way more attractive than angel investing for financial return. Angel investors’ money gets locked up for 5+ years (maybe even 10 years), so you face a significant illiquidity punishment relative to the S&P or even real estate. Second of all, your money gets massively diluted by follow-on capital. The more money a startup raises, the more you get washed out as a little guy who can’t defend pro rata.

But from a social returns perspective, you face neither of these problems. Not only are the social returns immediate, they also get reinforced by follow-on capital raises. That $50 million Series B for your favourite portfolio company might have washed you right off the cap table, but it’s an awesome achievement socially. As a bonus, even if the startup ultimately fails or you get recapped out of the picture, you still get a lot of the good will and recognition you were after. Even the downside scenario is pretty good, so long as you’re a good citizen about it.

There’s a very important trick going on here that I want to reemphasize: the social returns to angel investing have superior deal structure dynamics than the actual money part, because the more money gets raised in follow-on rounds, the more your social return compounds - on contrast to your equity stake, which gets diluted down. This solves an important coordination problem for the angel investor, during the window of time when they’re thinking about the social side of the balance sheet. “We don’t know how much money will need to be raised in the future” drops out of the problem statement.

This superposition of financial versus social returns, when considered in one investment, gets everybody in the round thinking in sync: “All right, we all know we’re here for an equity deal, but we’re going to follow social rules as though this were a gift exchange - I gift you capital; you gift me shares. We’re going to follow the rules of gift culture, and its insistence on accepting gifts and reciprocating them; and embrace the high-bandwidth communication channel for ‘figuring out what we’ve got here.’ (Described above.) And then at the end of the gift exchange, we’ll see if we have a path to doing a round that successfully gets us to the next round.”

It’s almost like a Shakespearian “Play within a play” setup: by play-acting one kind of investment, we catalyze another kind. (You know what’s an interesting historical analog? Mike Milken! One of the important things Milken figured out in creating the junk bond market was that “these things need to be sold like equities.” They needed a story to them; even if they were nominally a fixed income product. Milken was a generational master of “create windows of opportunity that didn’t exist before”, and I wonder if this idea would resonate with him.)

Multistage Bagholding Etiquette / the gift of grading on potential

This mixed motive of “investment-as-capital, investment-as-gift” is easier to accept for angel investors. They come in early, invest their personal money, and are allowed to have extracurricular motives. But it also applies to VC firms chasing hot deals, at least a little bit. VCs care about signal just as much as startups or angels do; and some are more disciplined than others on price. But there is an important social grace given to investors who pay arguably-inflated prices that startups need to keep their J-curve going.

Remember that the hard problem of financing innovation is the uncertainty around how many financing tranches you have until companies are graded on results as opposed to on potential. In any given financing, investors have to decide whether this is a “potential” round or a “results” round. The investors leading this year’s round cannot communicate with the people who’ll do next year’s round. If you could know with certainty which kind the next round would be, you could price today’s opportunity more straightforwardly. But we can’t time travel yet (until we beat thermodynamics), so the best we can do is send signals to the future, in the price and term structure we agree to today, about the gift being given today of grading the company on potential.

The gift-culture long game, which has been going on for decades in Silicon Valley, creates confidence that we can pass this “gift of grading on potential” forward, round after round. You can raise a Series A on the story of what the Series B story will be: “The appropriate thing would be for the next round to be priced at 40 at 150 post; can we count on people playing ball?” Everyone is gifting each other permission to not second-guess anything and go for the crazy outcome as opposed to the rationally optimal outcome.

We have to talk about bubbles for a minute here, because speculative bubbles show what this looks like with the mask off. There’s plenty of great writing on the importance of bubbles in creating financial maneuvering room for industries getting off the ground - read Byrne Hobart’s book Boom!, and Bill Janeway’s Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy - but I have one thing to add about bubbles that I never hear mentioned. Everyone talks about bubbles as times of lots of optimism, lots of FOMO, lots of irrational exuberance. But you know what else you see a lot of during bubbles? Generosity. This makes sense! Everyone is flush with success, and in good times like those, we are gift-giving people.

Gift Culture rules come to the forefront during bubbles, adding yet another reason why irrationally exciting possibility spaces seem to open everywhere as investment opportunities. During bubbles, there is no coordination challenge whatsoever; not only do you know that the money will be there next time (because number go up), but you also know the money will be there next time because we’re all good for picking up the tab; everyone knows the rules. That’s quietly closer to the thought process behind a lot of follow-on VC financing during good times: it’s not always strictly about number go up; it’s also about signalling to other players in the game, “We are good to pick up the tab.” Sometimes the tab is sickening at the end of the night; like the hangover after 2021 that left us with thousands of stranded zombie unicorns. But, rules are rules! That’s why I’m fond of saying that Silicon Valley is a “controlled bubble.” The social rules of the place keep it behaving reasonably predictably, and why we can reasonably count on multiple rounds of funding coming together to keep gravity turned off for just long enough for startups to grow through it.

Demo Day

Gift culture inside innovative companies matters too. The best illustration is Demo Day, the internal magic trick that makes building the unknown actually work. Not only are “Demo Days” an important component of the startup-investor gift exchange, they’re also an important ritual inside companies where people come together and figure out that essential question, “What is it that we’ve got here?”

You’d be surprised, but even projects with well-defined aims and timelines still have to contend, at the real coal face where the work happens, with the same problem startups face: we don’t know quite yet how this will take shape, or how long it will take. Traditionally, the way you’re supposed to tackle this problem is rigorous Project Management where you try to be as realistic as you can with specs and estimates. But if you want to ship something that’s actually great, you need to discover the best path available; and not just by thinking about it, but actually by building and tinkering towards a goal of some sort.

The answer to this problem is “Demo Day”, which when done correctly, is a very serious ritual that everyone understands is a gift exchange. You show up at demo day, and give gifts of what you’ve worked on to everybody else. And the rules of Demo Day state that everybody has to accept the gifts, and celebrate them. Demo Day is the one reliable time where people actually listen to you when you go into exploratory nuance of possible paths forward. That kind of open-minded curiosity is supposed to happen at brainstorming sessions, alignment meetings, whatever; but no one is actually listening in those meetings. Demo Day is when people actually listen.

The fact that everybody actually listens during Demo Day is why the actual outcome of Demo Day isn’t just good vibes: it’s alignment on work going forward. (Paradoxically, the way you achieve this is by no one ever talking about ‘alignment’ at Demo Day!) The rules of gift culture compel us to accept the gift of possibility, reciprocate it, and pay it forward. And just like in the startup-investor gift exchange, the reason why Demo Days create ongoing lift to projects is because there is another Demo Day next week, and the week after that. Everybody participating knows that we’re in a repeat-game situation, and feels a certain pain of dishonouring the gift if they revert to “the safe, rational, average path forward” by the following Demo Day, rather than digging and pushing to find the actual golden path of progress.

As before, we can think of this as an inversion of the Market for Lemons problem. In a traditional project management regime, you’ll quickly lose the trust of others if you constantly bring forward out-of-band proposals that don’t confirm to “the plan”. The magic of Demo Day is, by putting planning aside for a minute and instead standing up a weekly Gift Exchange, you radically increase the communication bandwidth of the team for discussing and synthesizing, “where should we be heading?” If you can keep up that culture of curiosity, while maintaining a cadence of shipping, you succeed along conventional metrics, and the score takes care of itself.

Gifts versus Slop

If you’re still reading in the hopes that we actually get to AI, thank you for hanging in there; we’re at that part now.

So, I think the obvious thing we’re already seeing is that it’s much, much easier to generate working prototypes. Both inside and outside of companies, we’re just seeing an explosion of top-of-funnel ideas that Replit or Cursor can very quickly stand up and make functional. And that’s great. Like I said last week in Have you ever seen a goth downtown?, I think the first-order effect is that more people can make things more easily, and that’s just straightforwardly a good thing.

There is a misguided belief out there that this is going to somehow reduce the number of funding rounds required to bring startups to maturity. Maybe it’s wishful thinking from seed investors who are tired of being diluted out of their great early stage bets, long for a world of one-and-done seed capital, and see AI as promising discontinuity from the status quo. I don’t understand this thesis at all; I think the more simple-obvious consequence is that this is just like when open source infrastructure (e.g. LAMP stack) and pay-as-you-go cloud hosting meant you didn’t need to raise a million dollars for Oracle before you even started building. That time around, more shots on goal meant a longer glide path for the winners to build distribution and reach maturity; I don’t see why this time would be the opposite. Eric Stromberg has the right idea in this mini-essay.

Funny enough, I think the best finger on the pulse here are the people thinking about building inside of big companies; and the “future of the product manager” discussion. Which goes, look, we can build and test prototype ideas a lot faster now; but that doesn’t help with the main problem of shipping inside big companies, which is the complexity of the beast. Wrangling internal complexity is oddly similar to gaining product distribution in that they’re both merciless work, and you’re on a quest for simplicity (but it’s a messy quest). Finding the the best path, early on, matters.

I think we’re back to gift exchange as the magic trick that gives us room to move, to really find what the group is capable of. I think it’s obvious that AI ought to increase the value and frequency of demo days everywhere, so long as demo days culturally remain gift exchanges. Because if you’re not offering gifts, you’re offering slop. It’s just more stuff that’s shouted but goes unheard. I think it’s pretty obvious that AI-generated software makes the Market for Lemons problem worse: you can ship a lot of shiny looking software that’s absolute garbage underneath the surface. But if you actually think of meaning of what you ship as a gift to others, you are going to care a lot more about its real potential, while recipients are invited to suspend disbelief about what’s below the surface and just think about the blessing of potential.

If you remember one actionable idea from this post, make it “Gifts and slop are opposites.” The world is getting inundated with slop, and what makes it “slop” is the fact that no message is really received by anyone. AI Slop is maybe the lowest-bandwidth communication channel ever made, which isn’t necessarily obvious. Gifts are the opposite of this, because gift exchanges invite us to actually receive information from each other.

I think the people who are going to be big winners in this new age of instant prototyping are the people who are exceptional at gift culture. Because they will understand the scarce resource of this new environment, which guess what, was the same scarce resource before too - the ability to coordinate people, over time, towards promising but unknowable goals. That’s always been the hard part, and it feels magical when we solve it.

If you’ve made it this far: thanks for reading! I’m back writing here for a limited time, while on parental leave from Shopify. For email updates you can subscribe here on Substack, or find an archived copy on alexdanco.com.