One way to think about employee stock option programs (ESOPs) is that they’re good because they align economic interests between the business and its workers. When the business does well, employees do well, too. Employees like it because they get to own a piece of upside; management likes it because it underscores common cause for working through late nights.

Most people in tech believe that systematically sharing upside exposure with employees is good and necessary, although a vocal minority disagrees. To them, the practice isn’t so benevolent: they see equity-based comp as promising the moon and the stars, and then forcing unknowing employees to subsidize the startup through its risky years in exchange for leftover upside that gets paid out last. We have this argument on Twitter every few months, and it tends to fall into the same rut.

I find these arguments pretty frustrating, because for the most part (and I am generalizing here) the discussion is framed around wealth distribution, incentives, fairness, and the overall question of “who should get what.” I get that these are important questions: motivation and team alignment are useful if you want to go build a business and change the world. But they end up as theoretical arguments, and they never seem to change anybody’s mind.

Meanwhile, there’s another way we could think about ESOPs. In this view, ESOPs are good, not because of mission alignment or fairness, but because they’re a well-crafted tax code / capital structure swap with a convenient side effect of fudging your income statement a little bit. Now that’s useful!

To me, this is a much more interesting way to think about them. It underscores the good about ESOPs (they are genuinely value-creative, as a well-constructed swap ought to be) the bad (a large portion of their appeal is tied to the tax code and GAAP rules, which have changed in the past, and may again) and the ugly (that part about fudging your income statement, which we’ll get to later.)

Stock based compensation helps startups defy the laws of gravity a little bit. This week we’re going to dig into how, both because they’re topical (this past week’s Twitter dust-up was prompted by a new Bernie Sanders campaign proposal to tax options at vest instead of at exercise; yikes!) and because I’m currently writing this newsletter while procrastinating on my own taxes, so at least I’ll feel like I’m doing something useful. Win-win!

ESOPs are kind of like insurance

In a funny way, ESOP programs are like insurance. They’re both the same basic economic proposition: you put in a small amount of money on a recurring basis, and then if some conditions are met, a large amount of money is paid out to you. In between, the money is held somewhere as a float.

The float is important, for a couple reasons. In insurance, that money gets put to work productively in the meantime. It’s like using a loan for leverage, except even better, because policyholders can’t ask for the same rights and covenants that creditors do. Insurance float is fantastic leverage in that sense, and you can turbocharge a business with it if used correctly. (Berkshire Hathaway runs on insurance float: Warren may preach “don’t use debt”, but watch what he does, not what he says.)

Stock-based compensation does something similar for startups. Traditionally, issuing equity grants to employees is supposed to be an economically neutral event for the business, just like buying back stock. It transfers wealth from one group of shareholders (the existing ones) to another group (the new ones), offset by a cash purchase from the latter. The business itself is unaffected.

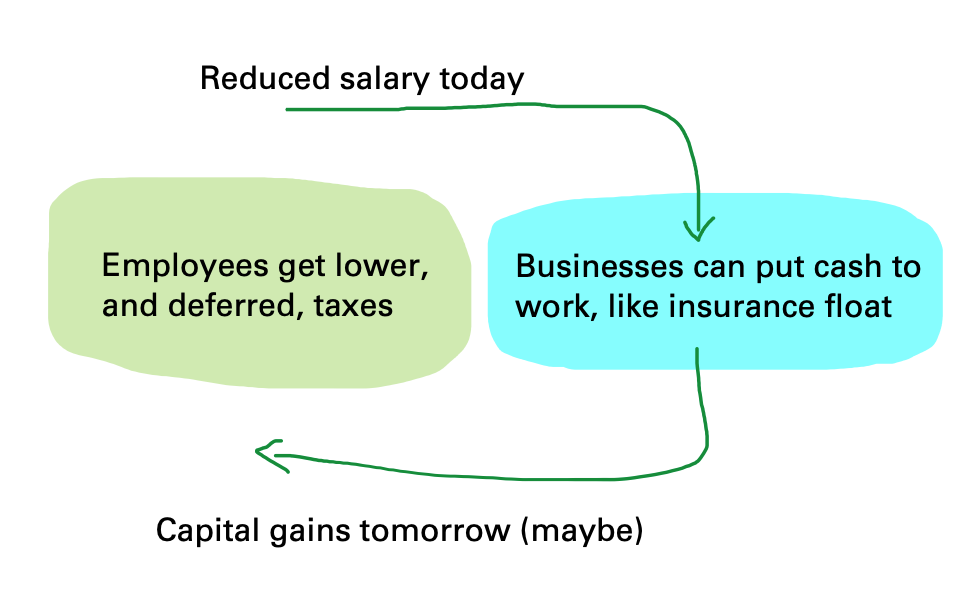

But it’s not totally neutral. There’s free juice to squeeze out of the orange here, and startups have learned how. Just like insurance, the key is in the float: employees “buy in” first (by accepting reduced cash wages) and then accept a variable payoff later, when the mature business issues and then sells employees their shares at a loss. In the meantime, the startup gets to put all of those savings to work. If you do this for enough employees, and enough for your compensation expense, it acts like a meaningful amount of leverage for these businesses, and they get it for free.

The main criticism of ESOP programs, which I mentioned at the beginning, is that employees get paid out last in a liquidation event. At the time they sign their compensation agreement, they don’t know how much more capital will get to cut the line in front of them; in fact, they may not know more basic things than that, like how many shares there are outstanding. Employees have the least amount of information and control over the money they’re contributing to the cap table.

But you know what, I hate to say it, that’s what they’re signing up for! The good news is that companies like Carta have done great work in helping employees understand the mechanics of their stock options better, and I suspect that as employees learn more about the mechanics of their stock options, they’ll actually appreciate them more, not less, as some people will have you believe.

Employees do get a major benefit back, though. They avoid paying tax; not only because capital gains are taxed lower than income, but also because appreciating stock is inherently tax-deferred by nature. Stock options and their cousins RSUs work a little differently from each other here, but the outcome is similar as long as you do the paperwork right. All of that wealth gets to grow inside the company tax free, and you only pay tax at the end when you cash out.

(Here, too, there’s an insurance parallel. If your house burns down, your insurance payment can be as high as it is because your premium payments grew tax free all those years, pooled with everyone else’s. Life insurance is even more explicitly a tax-advantaged investment vehicle. The IRS pays you to be insured.)

Take a minute to understand this swap. Both parties win here. Employees get to take advantage of something the business can’t: substitution of income tax for lower and deferred capital gains tax. Startups can’t take advantage of any equivalent, as fast-growing, money losing businesses that have no earnings to tax in the first place. Also, they’re not people. But employees sure can; even the hefty tax bill you owe at the end is way better than if you’d been paid all along in cash, or with other substitutes like phantom shares.

Meanwhile, the startup gets to take advantage of something the employee can’t: all of that float. Yes, the employee could put that cash to work, but probably a lot less effectively than the business can. To you, a dollar invested into wealth creation is going to eke you out some return in your 401k, which is perfectly fine; but to a company that’s doubling in size every year and running on VC jet fuel, every dollar you can borrow from your employees is worth ten or more down the road if you succeed. To you, it’s just cash, but to the startup, it’s leverage.

That’s why I think the insurance analogy is actually a pretty good one. Insurance isn’t only about pooling resources and risk, it’s also about putting money to work in a really powerful and tax-optimized way, so that the payoffs - when they come - can ring the bell especially hard.

At its best, ESOPs do the same thing; they are genuinely value-creative, all just by organizing people and their money and their ownership of a business in the right arrangement.

ESOP compensation can make businesses look better than they really are

If only it stopped there. Some businesses take this little swap one step further, and add some sleight of hand to it.

The short version of this sleight of hand is: if you’re paying a large percentage of comp in stock instead of cash, it’s pretty easy to misrepresent the operating economics of your business as being better than they are. Look, you say, in this time period, I made X much revenue with only Y much expense, employees are happy, and the business is happy!

Sure, but the expense is there - it’s just in your balance sheet, instead of in your income statement. This trick used to be standard practice, and although changes to GAAP rules in 2002 made it harder, it’s a bit of an open secret in the tech industry that we still do this; just a little less, and under legal cover.

Here’s the longer version. If you issue stock options to your employees as part of the salary that you’re paying them, then in a general sense they are an expense, just as wages are. Where do they show up in your accounting of how your business works, when you present it to investors and outsiders? And how much are they worth? This is a harder question to answer than you think, because valuing options of private companies isn’t so straightforward. You can make a case that they’re super valuable, or that they’re worthless.

There’s a classic dilemma here: on the one hand, you want your employees to understand that these options are valuable, so that you can effectively use them to negotiate compensation. You’d also love for the IRS to understand that these options are valuable, so you can claim them as expenses against your income. On the other hand, you don’t want to present them to your shareholders like they’re this huge expense, because it makes your business look less impressive. Ideally, you’d want to present them as not even an expense at all.

Until the early 2000s, you could literally do that. When businesses advertised stock options to their employees, and calculated expenses for tax purposes, they quoted the market value of the option, which is the fair value that someone would pay for them if offered. Even if you’re selling options at-the-money (an option to buy a $35 stock for $35), their fair value is obviously higher than zero; both because there’s value in the volatility, and there’s value in the ability to wait.

But when it came time to calculate expenses for quarterly earnings, they'd account for their stock option grants using the intrinsic value of the option. You could say, look, our share price as of last round was $35, and we issued these options to buy shares at $35, so clearly their value at that moment in time was 35 minus 35, which is zero. Up until 20 years ago, this was pretty widespread practice, and you can see how even if legally permissible, it was kind of dishonest.

Eventually the hammer came down, as the Financial Accounting Standards Board (who writes the GAAP rules for American financial institutions) issued a directive saying, we see what you’re doing. This is not a victimless crime; it’s misleading to investors, who own less of your future earnings than they believe. You need to calculate a fair market value for these options, and then account for them correctly in your income statement, or else face GAAP noncompliance. So nowadays, when companies issue stock options to employees, we actually go through the trouble to calculate a fair market value for those options.

But it’s this big open secret in tech that we still mischaracterize their value to some extent. These are private companies, so you can’t actually measure anything you need in order to calculate fair value; you have to infer them from public company comparables. But startups and their public comps are not at all the same! Your startup is volatile by design, whereas you can go find the most stable, boring, comps within a stretch of the imagination to use in your math. It’s entirely silly to believe that a startup’s closest comparables for option valuing purposes are other companies in its sector, rather than other companies at their stage.

Your valuation has to stand up to audit, but that’s not hard. There’s no way to actually calculate this number definitively. Yet there are tons of ways to defensibly come up with estimates that everyone knows are way low, but where the math checks out. (Meanwhile, it helps lower the taxes withheld from employees when they receive their options, which is much smaller than the taxes they pay if the company wins big, but is still meaningful - everyone pays those, not just the winners.)

This is a bit shifty. It’s less egregious than before the FASB ruling, but it’s the same kind of misrepresentation - just to a lesser degree. Of course, VCs understand what’s happening perfectly well, and they know how to account for it. They look at the cap table, and option pool size, as a way to understand how much the business relies on equity comp. In fact, they encourage it; it’s a win-win deal for the company and the employees that they want to support.

But public market investors, who expect compensation expense to show up on the income statement, aren’t used to having to go dig for them, hidden in your balance sheet. To be clear, it’s much less bad than it used to be; but it’s still a thing: heavy ESOP compensation makes the operating characteristics of businesses look better than they really are. And that makes prospective investors believe they’re buying a larger percentage of the businesses’s future earnings than they really are. It turns out that free money was your money. Oops!

ESOPs help defy gravity, just like everything else about startups

There are some noteworthy smart people out there whose opinions I respect that do not like stock-based comp at all: as the line goes, “in private companies they’re a scam on employees, and in public companies they’re a scam on shareholders.” Hopefully at this point you get the basis for these arguments, even if you don’t agree with them.

Here’s how I think of it. Again we come back to this recurring theme of this newsletter, “startups aren’t economically sensible”: startups don’t really work unless you have a way to temporarily turn gravity off. We’ve talked about lots of ways that Silicon Valley has learned to do this: angel investing for social status as a subsidy; VCs learning bidding conventions in their signalling, and portfolio construction that helps the math work; social contracts in the tech community that reduce friction; the recurring revenue business model; and more.

The stock option swap / sleight of hand we’ve talked about today is yet another one of these things. It’s a clever arrangement between the tax code, the cap table, and investor assumptions that helps startups defy gravity just a little bit longer. Is it a bit of a hack? Of course it’s a hack. Early on, it’s a hack on employees being all-in with startups; later on, it’s a hack on public market investors and how they look at companies differently from VCs, which kind of reverses that previous hack while keeping gravity turned off for a little while longer.

So what’s the point? Well, I warned you, there is no point. The point is for me to procrastinate on doing my taxes, and I think we’ve achieved that. But if you’re not already fluent in this stuff, hopefully this illuminates a few of the mechanics going on underneath the surface of employee stock options, and the incentives and alignment they do (or don’t) supposedly create.

Permalink to this post is here: Employee Stock Options: free money, kinda | alexdanco.com

Several weeks ago on this newsletter, we talked about Counterfeit Food, and more generally how the rise of aggregators is creating new forms of distance between consumers and what they consume, and hence new opportunities for counterfeiting.

Check out this story from the music industry, which predictably faces a similar problem:

This is a pretty strange accusation, and I have no idea if it’s true (or what complicating factors I might be ignoring), but the claim is that Spotify themselves are incentivized to stream fake music in order to lower contractual payouts to real artists on real labels:

The hypothesis, later confirmed, was that many of these artists were, in fact, “fake” (i.e. pseudonymous) names attributed to tracks created by composers signed to Epidemic Sound, a Swedish “production music” house. The unproven inkling amongst major music labels was, and remains, that Spotify pays a lower royalty rate for these songs than it does for tracks from “real artists” vying for the same playlist spots.

Why? Because Spotify pays out royalties on a pro rata basis. This means – as explained on Rolling Stone previously – that the firm divides its total industry payout across the entirety of artists on its platform, based on their portion of overall streams. The important bit: if “fake artists” are paid lower contractual royalty rates than “real” acts, and then, driven by playlist inclusion, claim a certain percentage of Spotify’s total monthly streams, Spotify ends up keeping more money. An ex-Spotify insider was once quoted by Variety as suggesting that this was a deliberate company strategy: “It’s one of a number of internal initiatives to lower the royalties [Spotify is] paying to the major labels,” they said.

Weird!

And finally, the comics section. This week, courtesy of the great state of Florida:

Have a great week,

Alex