You may have contemplated, or been asked at some point: “How will homeownership and residential real estate change after Covid?” In my experience, most of these discussions become far-fetched hypotheticals about remote work, the role of cities, and other fairly myopic perspectives from the Zoom-Bourgeoisie.

But there is one specific way where I could see Covid having a pretty significant impact on the way that housing works in specific cities, and on how homeownership works there for regular people.

Homeownership is a peculiar asset class. Most of the time, when we think about assets and why they’re valuable, we think of them in terms of what they enable. When you buy equity shares in a business, commercial real estate, treasury bonds, or other assets, the asset typically derives its value from what it makes possible. More can happen in a world where the asset exists than in a world where it doesn’t. Value is created, the asset captures some of it, and that’s what you’re buying.

But residential real estate is different. When you buy a house on a residential plot, a large part of the value of that house is in what’s not possible, and in what it excludes. Part of the value of your home lies in the zoning laws and building codes that prevent your neighbour from tearing down their house and putting up a bar, or a retail store, or a condo. The value of a good school district isn’t just that your kids get to go to that school; it’s also that other kids don’t. (That’s uncomfortable to say out loud!) The price of residential real estate reflects everything it’s not; and can’t easily become.

This is why there truly is not a “free market” for housing in the same way there can be for goods and services. The asset you’re buying and selling is entirely a product of the law and regulatory environment that dictates how the asset can be used, how it can’t be used, and how it can be bought and sold.

As a homeowner, you’ve bought a bundle. You get a home, leverage, tax breaks, and most importantly to this discussion, you get friction. You can frame that friction in a positive or a negative light: proponents will argue that you need these rules in place to protect residents from displacement, preserve local social capital, and protect the intangible but undeniable value of neighbourhoods that have accumulated character over time. Opponents see this behaviour as “pulling up the ladder behind you”: once you get into a neighbourhood, residents typically act and vote in ways that support their neighbourhood staying exactly the way it is: opposing more density, multifamily buildings, and especially subsidized housing.

Not all housing works like this, mind you. When you buy a downtown condo, you do not have a whole lot of influence over what happens around you. If you own a rural plot of land, there may not be many rules over what your neighbours can do with theirs. The exclusionary value of residential real estate is most concentrated in where that exclusion is most consequential: 1) single-family zoned neighbourhoods; 2) in fast-growing or highly unequal cities, where 3) development laws and zoning codes in place are expected to persist.

That last part is important: it’s not enough for that exclusion to exist; people need reason to believe that it will continue to exist in the future. In most cities, it’s a pretty safe bet to count on that kind of persistence, because it’s the emergent product of a system of local influence that has evolved over time and accumulated a lot of inertia.

The simple way to think about that system is as a three-way power relationship between developers, politicians and homeowners: the developers want to do stuff, and homeowners want them to not do that stuff. Politicians influence the compromise through immediate decisions and long-term policies: they want economic growth from development, but they also want votes from the homeowners. Every municipality is a little different in how this triangle relationship has evolved; but once it’s in place, it’s pretty hard to change.

In a world with few building restrictions, you'd expect to see positive feedback relationships around growth: investment spurs more investment. However, in a world where local residents have influential power, you reliably see an offsetting negative feedback force from local opposition: more development (developers trying to change what’s there) creates more resistance from residents as they organize and focus on blocking that change. In most North American cities, those feedback loops are a reliable form of inertia.

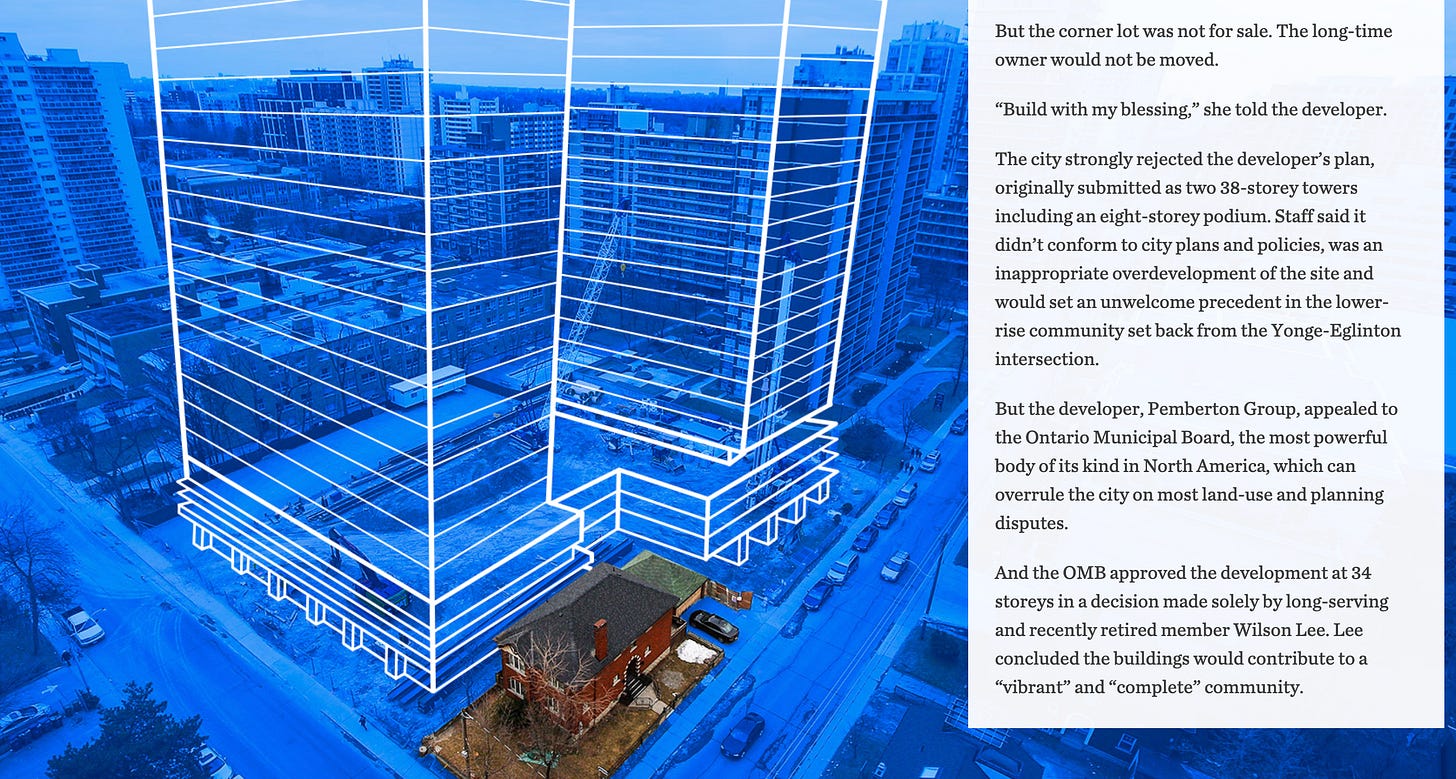

But not everywhere. Toronto is an instructive example for what happens when those inertial forces are disrupted or circumvented. Unlike virtually every other North American city, local elected leaders and planners are not the final arbiter of what gets approved for development. We have an institution called the Ontario Municipal Board, which exists at the level of the province, and has near-total power to override local planning decisions.

Initially, the OMB was imagined a “development-neutral” entity, not strictly pro- or anti- growth, but meant as an appeals tribunal for specific development decisions. The OMB’s job is to consider all hard evidence brought forward to the hearing, and then make the appropriate decision around whether that development is in the best interest to proceed. In practice, this makes OMB planning decisions easily influenced by developers (who can spend money on planning, expert opinions, and other supporting “evidence”), and hard to influence by homeowners, whose main currency - their votes - isn’t worth much here.

(Illustration and Copy from this Toronto Star article)

What this means in practice is that, although the OMB does not have the power to actively change local zoning rules, the minute that city zoning decisions get made, developers now have a straightforward path to propose, approve and build the maximum-sized project now permitted. It’s a fairly ham-fisted way of promoting growth, since this tends to overwhelm the subtleties and locally-crafted plans for specific areas, and anger local community members. It also effectively severs the negative feedback loop where homeowners had power to block or mediate individually proposed local developments.

Instead, homeowners here can only really fight development at a larger scope, like rezoning decisions. But those decisions are years-in-the-making, top-down decisions with momentum behind them than individual development proposals. It’s a lot harder for individual neighbourhood groups to block a rezoning decision than a specific new condo proposal. Consequentially, although Toronto certainly has its share of bone-headed individual development decisions or zoning choices, and we have a well-deserved reputation as a city who continually devours itself, we are nonetheless doing an okay job at the hard and necessary thing we need to do, which is to get the big planning and rezoning decisions done, and build a ton of dense new housing. Still not enough, mind you, but we’re sure trying.

So what does this have to do with Covid? It’s an instructive example because the OMB severed the local feedback loop usually in place between homeowners and local politicians, moving mediation to different levels of government (the province) and different stages of community engagement (larger-scale zoning decisions, rather than individual developments). And one pattern we’re seeing a lot with Covid - not just with city governments, but anywhere - is that Covid has shaken the inertia out of everything. And a lot of old feedback loops keeping things in place (e.g. the relationship between corporate IT departments, vendors, and consulting firms), which have been held in place under the weight of their own inertia, got shaken out really quickly this year, as people have moved to take advantage of the crisis and advance their goals.

The Toronto example may be instructive for other cities in the wake of Covid, as cities scramble to put in place new policies that both mitigate - and in some cases, exploit - the unusual situation created by the pandemic. The one common effect that Covid had everywhere is it reset all the inertia. Budgets have changed, priorities have changed, and a lot of city-building projects have gotten fast-tracked as planners and politicians try to seize the moment and advance their priorities.

One of the laws of systems is that they’re really hard to change once they’re established; but one way they do change is that emergency patches to the system, meant to be temporary, become permanent. I would not at all be surprised if some emergency “patches” we’ve made to city governance, or will make in the coming year, introduce temporary short circuits to the development process - just like the OMB did in Toronto - which find end up becoming permanent.

When we look forward a few years and ask, “what will be the longest-lasting effect of Covid on homeownership and real estate”, most of the predictions and takes you hear involve people and their preferences: like “People will leave cities when they can work remotely.” But if you ask me, I’ll bet you that the most consequential impact of Covid on homeownership will be the temporary short-circuits and policy circumventions that cities and local governments set up to enact their pandemic agendas.

In the short term, like the next 3-5 years, this change will probably manifest itself in specific developments, rezoning decisions, and civic projects that could never have advanced before - even more likely if we get a round of fiscal stimulus after the election in November. But in the longer term, Covid’s real legacy for homeownership and residential development may be the temporary patches, circumventing local feedback loops, that become permanent. When they stick around and become permanent, they could really change the balance of power between people, politicians and developers in different local markets - maybe with some unintended effects, like what happened here.

Permalink to this post is here: Covid kills inertia, homeownership edition | alexdanco.com

Something neat to highlight this week: the VC firm NFX asked their founders what were the most influential or interesting essays on startups and tech over the past year, and one of the essays they selected was my newsletter issue from back in January, Social Capital in Silicon Valley. They then commissioned audio versions, which you can find here if you’d like to listen to it that way:

Social Capital in Silicon Valley: the NFX Founder’s List | Alex Danco

A few more reading links for the week:

Audio’s opportunity and who will capture it | Matthew Ball

Buy now, pay later | Marc Rubenstein

A big Shopify launch: our new wholesale marketplace, Handshake, officially launched earlier this month. For merchants who want a really simple and easy way to buy wholesale that’s interacted directly with your Shopify account, or alternately who want to sell in bulk to other merchants, check out Handshake and please spread the word.

And finally, this week’s Tweet of the Week, which made me laugh the hardest: (you’ll have to click through and watch the whole video to get the real effect; it’s pretty great)

Have a great week,

Alex