The Kids are Alright: An Interview with Eugene Wei and Julie Young (Gift Culture, Part 4)

Two Truths and a Take, Season 2 Episode 31

Welcome to the fourth and final segment in this series on Gift Culture at the Online Frontier. If you missed any of the first three, you can catch up here:

Gift Culture, Part 1: Homesteading the Twittersphere

Gift Culture, Part 2: The SE Suite, An interview with Julie Young

Gift Culture, Part 3: Scarcity Status versus Abundance Status

Today Julie is back with us to help close things out, along with our second very special guest, coming in to bat cleanup: Eugene Wei.

If you’ve spent any time on Tech Twitter (or even just reading this newsletter), you’ve found Eugene’s Tweets, writing and exquisite insight everywhere. (You can read his essays here.) Eugene has worked at the intersection of tech and media at Amazon, Hulu, Flipboard, Oculus, and spent a year in the middle of it in film school. He recently wrote a notable essay on internet status and social networks that helped inspire this series:

Status as a Service | Eugene Wei

Please enjoy as Eugene and Julie chat about the early internet, forums and newgroups, the path to today’s social networks, social status and gift culture, and how teenagers always show us the way.

Alex: I want to start by asking both of you a question, and this is a question where every time I ask it always ends up revealing something fascinating and interesting. The question is: Where was the first place you Posted?

Eugene: My very very first post was on some BBS a friend of my cousin’s ran when I was in high school. We used these BBS’s to trade shareware or ripped games to play on our PCs. The first time I chatted live with someone was on a BBS, it was as magical as Alexander Graham Bell making the first phone call.

But perhaps my first real public post was in some newsgroup, it may have been rec.arts.comics.misc when I was a junior or senior at Stanford. This was before Mosaic had come out so newsgroups were like the only online communities to hang out in.

The internet population was tiny compared to what it is today, and these communities felt cozy and intimate. A lot of the people who were in these groups were accessing them as students at universities or workers at government agencies. It was a geeky crowd but everything felt more civil.

Julie: I first posted on Xanga (hell yeah), but it wasn’t until I got a Myspace in 6th or 7th grade that I really got into “social networking.” I can remember learning how to copy/paste HTML into my page so I could have a cool background. I spent HOURS looking for the perfect emo song (remember when our profiles could have SONGS?) that would cryptically convey my deep, complicated 7th grade self.

AIM profiles weirdly played a big role in middle school social networking, too. I can remember obsessing over reading through all of my classmates’ AIM profiles. It was the first thing that got updated whenever someone had a new bf/gf lol. It was also really cool when someone made a shout-out to you in there. It was a way to show off that you were friends with someone. I can VIVIDLY remember feeling lame because I didn’t have enough friends to shout out in my profile so I actually MADE SOME UP (“you don’t know them, they go to a different school”). 😂

Alex: Yeah, AIM. AIM was honestly the whole world. I’m floored that no modern messaging service has brought back away messages. For me, though, the first place I ever really posted posted was the Wizards of the Coast online MTG forums, back around 2001-2003. It looks like WotC shut them down several years ago, which is a bummer, although understandable since I’m sure a lot of it had naturally migrated over to Reddit and Tumblr by then.

Still, there’s something to be said for those intensely domain-specific newsgroups and forums and the real sense of community they created.

Eugene: A year or two out of college, I really got into the X-Files, but only after two seasons of the show had already aired. DVDs hadn’t launched yet, and those episodes weren’t in syndication, I didn’t know how to find them. So I went on some X-Files newsgroup and asked if anyone had taped the first two seasons and would be willing to transfer them to VHS tapes for me. Someone responded that they would if I sent them enough blank VHS tapes.

I mailed this total stranger a box of blank VHS tapes and a few weeks later the box came back, with every episode taped and labeled. Back then, to transfer episodes, you had to record each one in linear time. At 24 episodes per season, that person had to run two VHS machines for 33 to 34 hours straight. It still might be one of the kindest things any stranger online has ever done for me.

Subreddits are like emergent newsgroups, but the general tone online is higher variance now. There are still acts of kindness and generosity, but also the possibility of much more random violence and trolling.

Alex: Eugene, you became initiated with the internet in a different time than Julie or I did, but I bet if we went back in time we’d recognize that a lot of the internet culture - so like the words we use for things, the speech patterns, the internet poster shorthand, which since grown and evolved and meme-fied - is pretty much the same. I’m curious what you think are the core tenets of internet posting culture, and internet “abundance culture” if you want to call it that, which we basically figured out early on and have since endured.

Eugene: That’s a really kind way to say, “Eugene, you are an old geezer.” Haha! At least I’m not a boomer.

Yes, I like to think of the early internet as the Wild West in early America, but even emptier, with no native population, and even more expansive. Just vast open spaces waiting to be built upon and claimed. Recall that this was a time when the leading search engine was Yahoo, with a hand-curated directory of all the sites worth visiting. We joke now about sometimes browsing online for so long that you reach the end of the internet, but back then there actually were days when I felt like I’d visited every website on the planet, waiting to see what Yahoo’s Site of the Day to be announced the next day.

There was no identity graph like Facebook back then, often all you had on someone was their email address. And while you might find a scant few nuggets of information by running their email address through a WHOIS, for the most part the internet consisted entirely of strangers.

So in a low-trust environment with total strangers, communicating predominantly via text, people quickly started inventing workarounds for the limitations of text. For example, one thing we’ve long known is that text often does a poor job conveying tone, especially subtle modes of expression like sarcasm or irony or jest. It took just a few instances of misunderstandings and bruised feelings before people invented emoticons. A well placed =) after what sounded like an insult would turn it into a friendly jibe.

But, more to your point, we did see a lot of the early signs of the gift culture you identify as characteristic of spheres of abundance. In fact, even minus an explicit identity graph, even minus explicit mechanisms of feedback and status like the “like button” or “upvotes” and leaderboards, you already saw, in newsgroups, an explosion of activity fueled by nothing more than intangible rewards like reputation.

In many newsgroups, volunteers would write and maintain an extensive FAQ, a convention borrowed from mailing lists. The more you contributed, the more you could make your reputation as a valuable member of a newsgroup. There were no usernames back then but some people adopted one for their posts and became known for those pseudonyms. All the motivational dynamics that would later allow for the building of something like Wikipedia from the community existed in forums back then.

Alex: Really reminds me of a line from ESR’s The Cathedral and the Bazaar on why open-source software communities produce such great documentation, even though writing documentation is the last thing that hackers themselves wanted to be doing:

Many people (especially those who politically distrust free markets) would expect a culture of self-directed egoists to be fragmented, territorial, wasteful, secretive, and hostile. But this expectation is clearly falsified by (to give just one example) the stunning variety, quality and depth of Linux documentation.It is a hallowed given that programmers hate documenting; how is it, then, that Linux hackers generate so much of it? Evidently Linux’s free market in [gift culture] works better to produce virtuous, other-directed behavior than the massively-funded documentation shops of commercial software producers.

Eugene: I do think we’ve seen a big shift in the internet abundance culture thanks to the commodification of interaction. In the early days of the internet, and even in the blog era, there were no simple one-click feedback mechanisms such as like buttons. To give feedback, to even exist, you had to post something. Even if it was typing out “Thx!” in response to someone’s post on a forum.

In the blog era, there were attempts to build out more systematic connective social tissue, like trackbacks, webrings, things like that, but these were completely trampled by social networks like Facebook which built from the social graph out, rather than from the content out. They built out social feedback mechanisms of unparalleled scale and simplicity.

But classic economic theory predicts that the costliest signals are the strongest signals, and something about just mashing like buttons as the basic unit of interaction in this attention economy cheapens the connections. You end up with a social graph of very weak ties.

In a way, the more costly signals required in the early gift culture economy of the internet allowed it to feel more harmonious despite being a low trust environment. Modern social networks are at a much larger scale. One might expect that with the more developed identity layer of today’s internet that trust would be higher. However, our largest modern social networks are built around public feeds where many strangers collide, and these companies haven’t solved the interactions between those people with low trust and often divergent viewpoints.

Another critical change from then to now is the rise of the machine learning algorithms that selectively amplify the distribution of certain posts. It’s difficult to describe how different the pre-turbocharged algorithmically determined feed internet felt compared to today’s hyper-accelerated information environment. Back then forums felt like cozy rural communes, today’s social media driven environment is like the urban jungle. To the extent that the feed algorithm is accurate, it feels meritocratic, but a lot of the content that gets amplified today is just clickbait or outrage fodder. This contributes to the sense of living in a high inequality information environment.

Users have so many repetitions on social media, they learn what the algorithms rewards very quickly. The rise of fortune cookie Twitter is in large part because posting pithy if somewhat trite aphorisms really works, many get hundreds of likes. Clickbait titles are commonplace now because they also work.

This is not to just be a “things were better in the old days” rant. But I do think in the era of growth teams running wild with machine learning algorithms, we accelerated distribution incentives to drive engagement before we really knew what incentives were being created in the internet economy. And now the larger social networks are grappling with some of the unintended consequences.

One of the refreshing things about TikTok is that its algorithm ends up being pretty harsh. Many creators may have one video that gets the TikTok FYP algorithmic boost, but then you browse their profile and see all their other videos have only a tiny number of views. These are like one-hit wonders in music. Even if you have one breakout video, if TikTok screens your next video to an initial test audience and they don’t respond, they will drastically reduce its FYP airplay. It’s harder to “game” the TikTok algorithm and that makes it feel like a more meritocratic attention economy.

Alex: When I think about where on the internet gift culture really hit its stride, and found a really resonant form factor for self-expression, the two places that come to mind for me are Tumblr and Snap.

With Tumblr especially, I feel like there’s an Almost-Fortune-Cookie level sound byte like, “In the year 2060 all of human culture will have descended from Tumblr.” Was Tumblr the very beginning of “post-internet scarcity?” It felt that way sometimes. It was the wackiest place, and yet there were rules, there was a highly evolved culture, that felt, as ESR put it, like “an adaptation to abundance rather than to scarcity.”

Eugene: I know so many people who’d still tell you that Tumblr is their favorite social network and that they miss its heyday dearly. In music, you might say that digital sampling and remixing mark the modern era in some ways. Tumblr was remixing brought to social media and does predict much of today’s meme-heavy internet.

Tumbling felt like surfing the mental preoccupations of very online people, their brain cells connected in a cultural mesh where text, images, videos, and ideas raced from one Tumblr to the next, mutating and recombining with every hop.

Perhaps because it grew up in an era of abundance, Tumblr was characterized by a deep well of generosity. It was expected that you might grab something from someone and remix it and pass it along for others to play with.

The closest replication of Tumblr’s creative network effects today is on TikTok where every video and meme can be remixed in multiple ways. Still, the bar for creation, despite TikTok’s really powerful camera editing tools, is higher than on Tumblr.

I miss Tumblr, though I suspect some of its spirit will continue to come back in different forms on our way to living in the metaverse, when sheer digitization of so much of our reality removes some of the last forms of real-world scarcity left.

Alex: Snap, also, just instinctively feels to me like a company that would get “new scarcity” right. Snap streaks and scores and Best Friends and all that were just really on-the-nose correct intuitions about what is scarce to us, or at least to teenagers. But the product has also continued to evolve, and still feel really fresh.

Julie: One thing I have always loved about Snap is that so much of the product mirrors the question, “What would this exchange be like if we were IRL?” In real life, pretty much all of our conversations are ephemeral, just like they are on Snap.

It’s also noteworthy that Snap group chats seem to encourage presence above all else. I mean, this is a multibillion dollar company that decided to send a freaking push notification when “someone is typing” lmao - who does that? It’s so ridiculous but also so core to what Snapchat is. I know from experience that it really incentivizes me to have real-time communications with someone.

When I speak to teenagers about Snapchat, a lot of them will say things like, “I add everyone on Snap - I only have someone’s phone number if we are REALLY close.” They’ll also say things like “Snapping someone is very casual. IMessage is very formal.” I’m not sure what exactly Snapchat is capturing here, but it feels scarce. While so many of the other social platforms are permanent and feel like a destination, Snapchat is more of a living, changing thing.

I do think it’s true that Snap streaks and Best Friends are correct intuitions about what is scarce to teenagers, but it also feels like these things are kind of antithetical to Snapchat. I don’t know why Best Friends got removed, but I’m guessing it was because it incentivized really thirsty behavior. I loved it, but it was honestly so annoying lol. I can remember sending and receiving so many pointless snaps in college just to make it onto people’s Best Friends, stalking people to see who they were chatting with, etc. Just a lot of really unnatural, unhealthy behavior - kind of like Myspace Top 8, except on a device that you have with you literally all the time for 100% of your communication haha.

Streaks are better because they aren’t a public leaderboard, but they’re still pretty unnatural. A lot of people maintain streaks just for the psychological satisfaction of seeing the number go up, not because they have a strong, long-standing relationship with someone. (People would lose their minds if streaks were removed though. My younger cousin has multiple streaks in the 1000’s - when she doesn’t have access to Wifi for some reason (ex: going on a plane), she will give her login to a friend so that she can log in and keep her streaks for her lol.) I truly wonder how this will end for that generation - I felt SO RELIEVED when I lost my one and only long-running streak. Maybe they will, too.

Alex: Would you say that Gift Culture is a part of how Snap works, or how many of these newer social platforms work, particularly TikTok? There’s definitely an element to it that you earn status by doing the work and giving it away, but with a very sophisticated expectation of reciprocation and returns to social status.

Julie: For the typical user, Snapchat feels more like a messaging platform than anything else. It’s not really designed for giving things away and getting status on a macro-level like Twitter or Tik Tok.

There’re definitely some more micro elements of Gift Culture, especially within group chats. When you capture a particularly funny moment perfectly within a Snap and send it to the group, you are rewarded with “saves” and “screenshots.” It makes you feel special and appreciated. Is this really Gift Culture though? Maybe it’s just what it feels like to have great friends. It’s sort of the digital equivalent to telling a funny story during Wine Night and being rewarded with laughter. There is some status to be obtained, but the cumulative effects are minimal.

Alex: See, to me that’s exactly what I mean by “it’s gift culture that’s found its stride.” Gift culture doesn’t have to be these big grand gestures. It’s the small, little things, like posting something funny and getting screenshots. Screenshotting someone’s snap is like an acknowledgement, “that was really good”. There’s more, though, I’m sure.

Julie: Ah okay, I see what you mean - I guess it’s just the status part that feels less scalable on Snap. Another thing that prompts some interesting discussions about Gift Culture is the Explore Tab under the lens carousel. There is an entire world of lens creators who put in time and effort to create cool lenses for Snapchat users. These lenses are accessible to anyone on the platform and can be added to snaps as a more immersive layer of expression. The Lens Studio platform requires some work to figure out how to use, but it is not an insurmountably difficult tool to work with. Lens creators are rewarded for their creativity and effort primarily with status. They aren’t paid outright through Snap, but a lot of brands will commission the most established creators for promotions and things like that.

This takes the concept of a “digital economy” to a more explicitly “metaverse-looking” level. It will be cool to see how it grows and matures over time.

I think Discord could be another company right now that is building around these ideas in the right way. Users can start servers and script user-driven processes within them. Status is explicitly determined by your ranking/categorization on the right side of the screen. Ex - there are huge singing discords where kids organize these huge singing competitions in the voice chat (complete with judges, song requests, etc.). The better you do in the contests, the more you (literally) move up the rankings in the server.

Alex: Do you think teenagers understand and experience gift culture differently than adults do?

Eugene: I certainly think teenagers more correctly value digital or intangible goods. I’ve written before about how unlike adults, most children don’t have other easy sources of status like a job, a house, a car, those types of assets. They are more time rich and thus will look to how they can earn status with that time most efficiently.

That’s always been true, but today’s teenagers are growing up with a much more fully developed virtual economy that they can participate in from the moment they are allowed a smartphone or access to a gaming device. Thus the ability to exchange that time for status is much better than previously. In another era, maybe you were the cool kid at your high school. Today, maybe you become Charli D’Amelio with tens of millions of followers on TikTok.

I can’t find this study anymore, maybe someone out there knows what I’m referring to, but there was this study done on Reddit where the payout could be in cash, an Amazon gift card, or Reddit Karma. And by a wide margin, users opted for the Karma, because they recognized it was way more valuable than the other two forms of currency because it had to be earned through a very specific type of exchange in the Reddit economy.

Alex: How would you describe the power that cool teenagers have? It’s like, they have power because they are able to give away something that no one, not even the richest or most powerful grownups, are able to give away. What is that though? Maybe it’s something so simple as they have time to spare, but it’s more than that I think. Maybe cool isn’t it, because the not cool kids have it too, a lot of them just don’t know it.

Eugene: I love that speech by Philip Seymour Hoffman as Lester Bangs in Almost Famous, when he tells the protagonist, William, “That's because we're uncool. And while women will always be a problem for us, most of the great art in the world is about that very same problem. Good-looking people don't have any spine. Their art never lasts. They get the girls, but we're smarter.”

And everyone who is or has been a teenager immediately understands just what he means. The teenage economy of cool is a savage yet intricately structured marketplace where humans have to work out how to survive in an open tribal landscape. There’s a reason so much YA fiction is dystopic and horrifying like The Hunger Games or The Maze Runner.

Why is it that cool is so often associated with teenagers? I suspect it’s because teens live at a very particular juncture in life. They’re old enough to be conscious of the dynamics of cool and social status, their tastes are developed enough to have a more refined quality filter on things like music and fashion and other consumer products, but they’re not so old that their tastes have ossified or that they’ve become captive to years of conditioning from the advanced marketing apparatus of capitalism or the sophisticated social conformity pressures of adult society. So we ascribe a more intuitive valence to their judgements of what is cool, what is not.

Since that confluence of conditions is restricted to that particular era in one’s life, it comes with built-in scarcity. It’s just tough to match that with another form of scarcity. Not impossible, just difficult.

Teenage cool also comes with a somewhat unique overtone of violence. We…errr, maybe I should say I (since I won’t speak for either of you, both of you may have been much cooler than I was in high school) certainly felt the sharp end of exclusion from the cool kids group at some points of my childhood. Teenage cool is equal parts love and hate. Late in life, people tend to embrace the things they love, but it’s your teenage years when the choice of what is cool to you also draws a sharp line around what is uncool. It’s equal parts embrace and negation.

I tend to associate teenage cool with a quality of nihilism. That mix of rebelling against your parents while fighting for survival in the social jungle that is high school while also grappling with the hormonal soup that is your body can give you an edge that is hard to sustain throughout life. At the same time, if you choose to dub something cool despite having to fight through a sustained fog of anger at the world, that is a real gift.

Alex: I was definitely never cool, although my teenage years were probably the local minimum of my relative awareness and social understanding of how the social economy worked, rather than the maximum as it is for many people. Still, you know who the alpha kids were; everyone did. From around age 10-18, between different schools and friend groups, I remained in more or less the same place: I wasn’t cool, and my group of close friends wasn’t either, but I was always close with one or two actually high-status people.

Mostly I feel like the popular kids then would’ve been the popular kids now, and the ones with social gifts and graces then would be the same now. But with one caveat. I wonder whether there’s been a change in how people perceive “trying”, if that makes sense. It used to be that you didn’t want to be seen striving too much. And I wonder if the internet and today’s social media, which is so performance-y, has changed that.

Julie: The fact that Gen Z grew up with such a mature digital economy makes them so much more skilled at working within it. We laugh about the fact that the most common career aspiration among young kids today is “YouTuber” - but it makes a ton of sense. That kind of career allows you to make content doing what you love, build a company, own your time, and (hopefully) earn a great living while doing it. The younger generation understands this and validates it more so than any generation before it. The concept of a “sell out” doesn’t exist for them - making content and monetizing what you’ve built are all indicators of success that give them status (rather than taking it away).

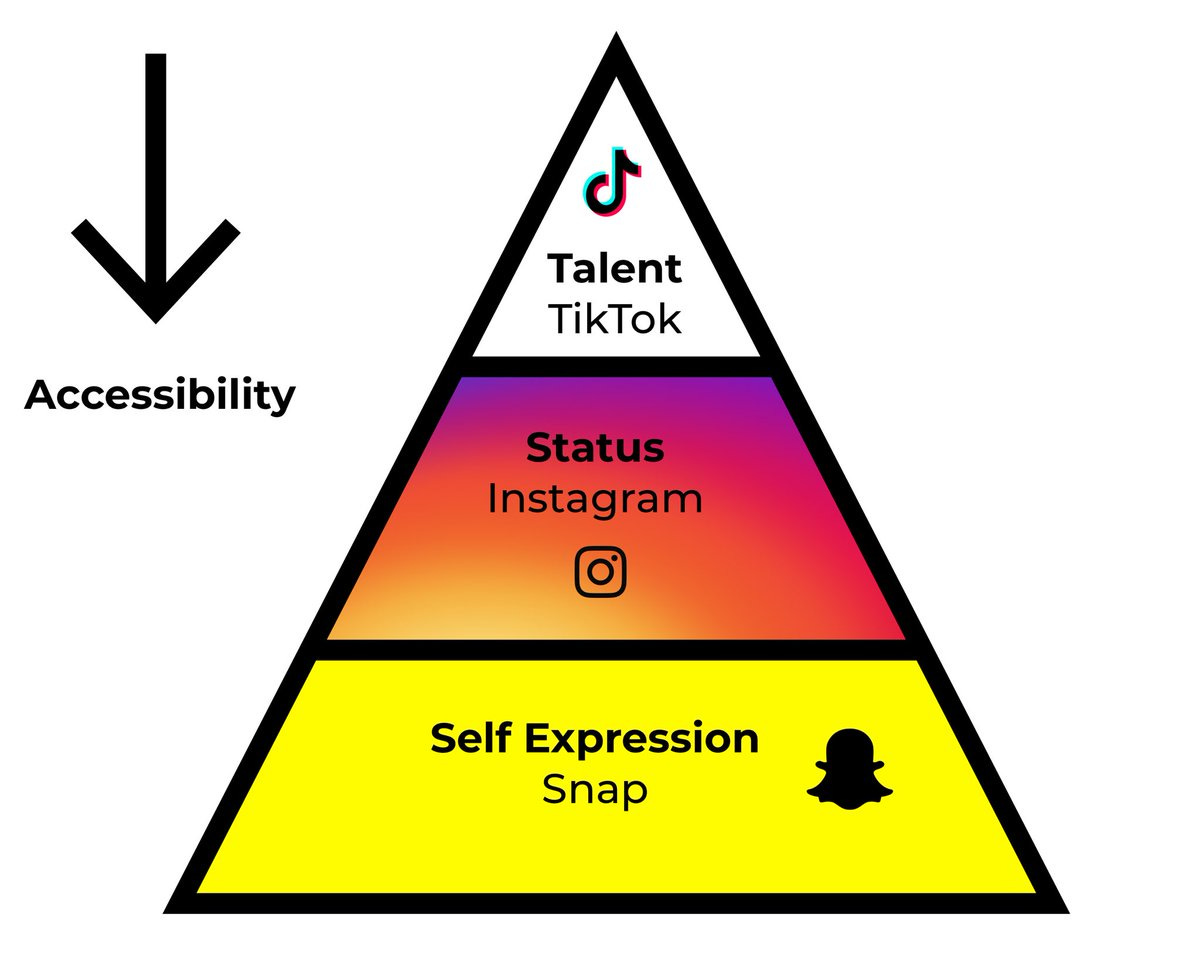

When thinking about generational differences, I like to think back to the pyramid you mentioned in Part 3. On the bottom of the pyramid, you have self expression (Snapchat), then status (Instagram), and then talent (TikTok). Millennials grew up with a dual expectation of both needing to obtain status online, but also needing to fit into the traditional professional world created by GenX/Boomers. We grew up “rolling our eyes” at the Kardashians’ ability to “be famous for being famous” but also loving to regularly tune in to the show.

Ultimately, I think forces like this made it so that millennials have trouble differentiating between the middle and the bottom of the pyramid. The average millennial does not see a difference between an Instagram story and a Snap story or a Snap group chat. (This is why we saw so many reporters writing stories about how Snapchat was dead when it wasn’t!) The average millennial sees almost all social media as a way to broadcast. When we “posted on someone’s wall” as a “message,” we pretended like we were “messaging” even though we knew that the “message” was really a broadcast to be seen and consumed by others -- it was a way to gain status.

Gen Z has a higher bullshit detector, presumably because they grew up with the more mature digital ecosystem Eugene mentioned. They have a much clearer understanding of the difference between messaging someone on Snapchat versus broadcasting on your story. On top of that, it’s well-understood that you will lose status if you confuse the two (after all, that’s what the olds are doing on The Facebook Dot Com!).

This more agile understanding of the digital economy helps explain why Gen Z is so much more prone to Internet entrepreneurship. Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok are incredible tools for broadcast - and for building a business around that broadcast content. When it comes to messaging friends and expressing themselves, they’ll go to Snapchat, iMessage, Discord, and Instagram DMs.

Alex: As tempting as it is to go on for pages more, I think we’re going to call it a wrap here - thank you so much Eugene and Julie for taking the time to share all of this with us! I had such a great time getting this together and I’m sure our readers will have an equally good time tuning in.

You can read more from Eugene here, and more from Julie here.

Permalink to this post is here: The Kids are Alright: an interview with Eugene Wei and Julie Young | alexdanco.com

This week, a bunch of news to share from Shopify-side:

First, Dev Degree admissions are now open for Fall 2021. If you’re interested at all in getting a computer science or software engineering degree, or know someone who is, Dev Degree is a pretty remarkable program. You’ll get 4,500 hours of experience over four years, and come out with the same credentials as a four-year undergrad (but with an enormous head start in joining the tech workforce.) You’ll also spend the majority of your time working on actual software projects inside Shopify, contributing actually valuable work. We have some Dev Degree students in Money, and they’re fantastic.

You know I’m not huge on the “college will collapse in a few years” train, which is fashionable in a lot of parts of tech. I had a great undergrad experience, I learned a lot, and I wouldn’t change it for anything. I don’t think you can flippantly say, “skip college and get some real-world training, it’s the future, go for it.” But Dev Degree is really something special. Oh also, instead of paying tuition, you get paid a salary. As you should! All told, when you add up your salary + vacation + paid tuition for partner programs, you end up getting paid something like $160,000 over 4 years. Anyway, if you or someone you know needs to hear about this, please send them here, Here’s an FAQ.

Other news from Shopify: Jon Wexler, formerly an exec at Adidas and best known for running the Yeezy product line (one of the most successful celebrity branded products lines I think ever?) is joining the team as VP of the Creator and Influencer program. Here’s an interview with Wex and Loren Padelford, who runs Shopify Plus:

Former Adidas Yeezy GM Jon Wexler is joining Shopify | Brendan Dunne, Complex

If you want to join us (and Wex), we’re still hiring for lots of roles, including two in particular I want to highlight: Director of SEO and Product marketing lead on Money. If either of those sound like you or someone you know, please check them out.

And finally, if you were curious how Shopify gets stuff done, JML made this video for Austen Allred (who had asked Twitter how big companies deal with internal collaboration and job-tracking), you might find it interesting:

Here is a fantastic conversation on Direct Listings, with Barry McCarthy, Spotify’s SFO, Greg Rogers, who was council on both Spotify and Slack’s direct listings, and Will Connolly from Goldman. It has some fantastic lines in there (especially from Barry) and is generally a great read if you’re at all interested in the recent innovation and experimentation around the going-public process.

Amazon drivers are hanging smartphones in trees to get more work | Spencer Soper, Bloomberg

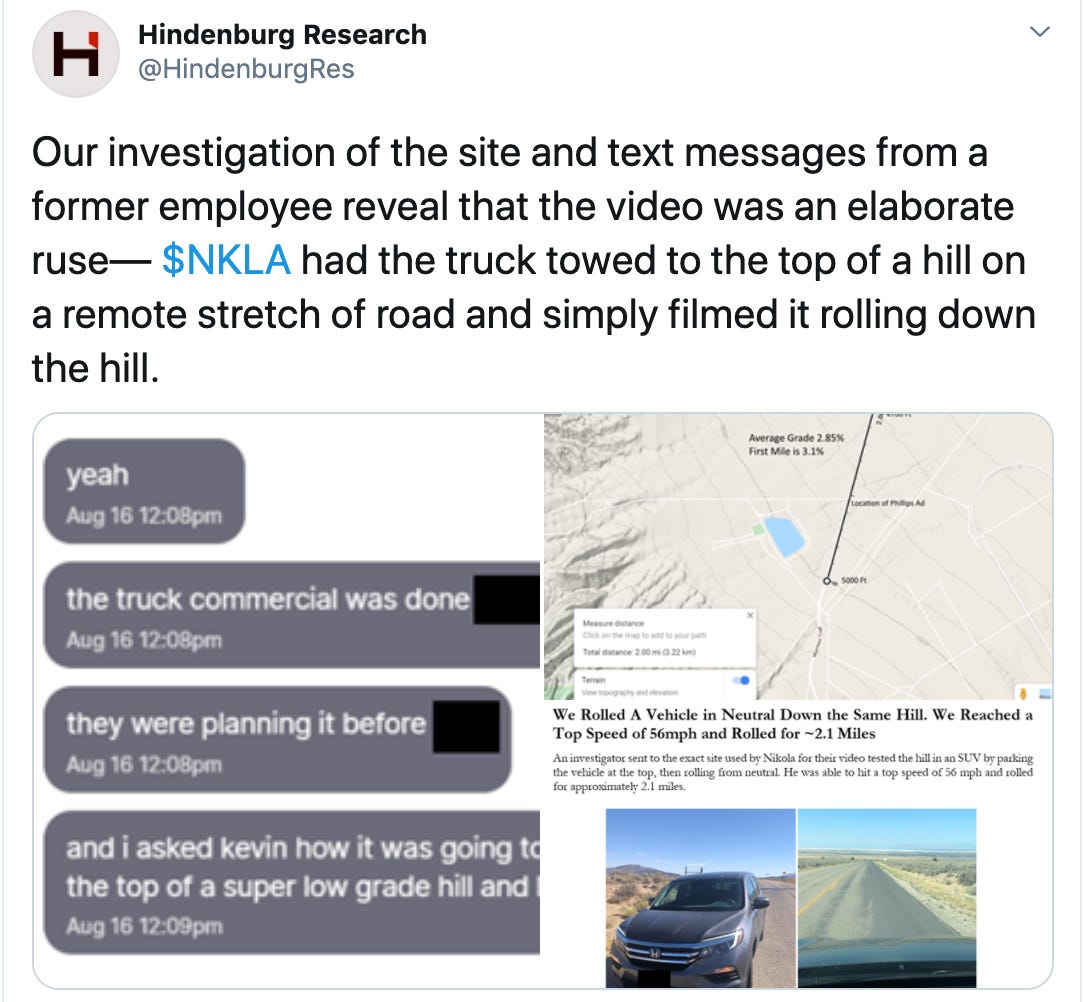

And finally, for this week’s Tweet of the week, if you’ve been online in the same places I have this week you know it’s obviously going to have to do with the Nikola short selling story. Read the whole thing, and here is the Twitter thread, but this part in particular just made me laugh so hard:

Have a great week,

Alex