Shopify, SPACs and Status: My Interview with Jim O'Shaughnessy (Part One)

Two Truths and a Take, Season 2 Episode 41

A few weeks ago I sat down over Zoom and recorded a podcast with Jim O’Shaughnessy, who interviewed me for his show, Infinite Loops. We ended up talking for over two hours, and it was one of the most fun and wide-ranging interviews I think I’ve ever done.

Alex Danco: Shopify, SPACs and Status | Jim O’Shaughnessy’s Infinite Loops

If you somehow don’t know him yet, Jim is both a legend in the asset management world, the author of What Works on Wall Street, and also one everyone’s favourite regulars on Twitter. (His command of the Gif keyboard is unmatched.) He’s also the patriarch of the O’Shaughnessy Asset Management Extended Content Universe (which includes Patrick’s Podcast Invest like the Best, where you can find an old episode of mine last year) and Jamie Catherwood’s finance history franchise Investor Amnesia. (It’s now an online course too, featuring some incredible guest teachers, and I highly, highly recommend you check it out.)

We covered four big topics:

Part 1: Shopify, Friction and Commerce

Part 2: Twitter, the World’s Learning Commons

Part 3: Founders and the Truth

Part 4: SPACS, Biotech, and Bubbles

For this week’s newsletter, please enjoy this edited and condensed transcript of parts 1 and 2, Parts 3 and 4 will follow next week. If you want to listen to the real thing, which I highly recommend for the full effect, you can find it here.

Part 1: Shopify, Friction and Commerce

Jim: Well, hello everyone. It's Jim O'Shaughnessy with my colleague Jamie Catherwood for another edition of Infinite Loops. I am delighted to finally get Alex Danco as my guest. We have been trying back and forth, and it's usually my fault, not yours. You've been very gracious. But welcome Alex.

Jim: First off, let's talk about Shopify. You've been there what, seven months?

Alex: Six months.

Jim: Six months. Okay. Tell us what's going on.

Alex: Boy. What isn't going on? Shopify is a big place and we're doing a lot of things. It is a wonderful place. I should preface by saying: I have so much fun working there every single day. I had some idea that it was going to be a good fit when I joined. But I have been pleasantly surprised every day at what an engaging challenge it has been. In getting to work there, and learning how to contribute and learning how to be useful to this company that's doing something fundamentally important, which is creating an easier and better and more rewarding path into entrepreneurship for people all around the world.

If you are a merchant today or over the past 20, 30 years, you have faced a lot of headwinds that are really tough. The path into small business, especially small business selling things, used to be this unbelievable way to create self-sustainability, create community, to create sort of pillars of the economy and of local ecosystems, because entrepreneurship and merchanthood was something that we celebrated in America and around the world.

And sometime, over the last, maybe 20, 30 years, things have kind of gotten off track a little bit. We've gotten a little bit too obsessed with convenience, a bit too down the path of consumerism.

Jim: Yeah.

Alex: Consumerism is the state of commerce and the state of being a merchant, where we're buying a lot of things, but buying it in a fairly low friction, low trust, low commitment kind of way. It's hard to be a merchant in that kind of environment. You're competing against the Amazons and the Walmarts of the world. Who, don't get me wrong, have done great things. We're not anti-Walmart. Walmart makes a good quality of life accessible to people in a way that was not possible before. That's a great thing. But it makes it hard to be a merchant who is selling something really special that you've put your life into learning how to create craft around.

It makes it hard because again, this is not really Walmart's fault. It's more the fault of... everyone. We've forgotten how to shop. We've forgotten how to be interested buyers. The art of merchandising and of commerce has gotten lost a little bit, especially into this new era of the internet where everything is just so convenient and so quick.

So enter Shopify. Shopify's goal is really to bring back a part of the world of commerce that I call “high trust commerce”. It's commerce where you have this ecosystem of buyers and merchants who are all deeply committed to the art of commerce. We're committed to this idea that maybe shopping isn't supposed to be this completely frictionless experience.

Maybe shopping actually needs a little bit of challenge to it, because the challenge is the fun. And the challenge of shopping is what makes it special, like finding this exact thing you want and building a relationship with a merchant and trusting them, and then getting joy out of the whole experience.

You can think of the first part of Shopify's mission is “making a very frictionless but meaningful path into entrepreneurship for merchants who want to create that kind of rewarding relationship with buyers”. Who really, really care about what they're selling. But then- and this is something that you can look to Shopify to do over the next 1 to 5, 10, 20 years - is not only help merchants succeed at being great merchants, but help the entire community of commerce. So buyers, partners, supply chains, marketplaces, advertisers, everybody, everybody in the ecosystem. Engage more with what we call high trust commerce. Which is just truly better off for everybody. So that in a nutshell, that's Shopify. That's what we do.

Jim: It's so interesting. I had lunch yesterday with Dan McMurtrie. I don't know if you know Dan.

Alex: You must mean SuperMugatu.

Jim: Oh, yes. That's who I meant. Yes. Yes. But his thing, one of his theses during the lunch was that we're moving so quickly to not only permissionless commerce, but to no thought commerce. In other words, they don't even consider what they're buying and they're buying. What do you think about that?

Alex: This is an issue we think about a lot. Which is: where should there be friction and where shouldn't there be friction in commerce. So there are many parts of commerce where there is friction in the process and that friction is only bad. Like, you do not want to have to think about how you're setting up your payment processor. There's no benefit to this at all for anyone. It should just work. There's no point of going through that struggle for a merchant. It doesn't teach you how to do anything. It doesn't level you up in any way that's meaningful for the part you want to do.

Jim: It grinds you down.

Alex: That is friction we want to just get rid of. But then there is other friction where you don't necessarily want to get rid of it, because it's very important. Think about the friction of figuring out how to land your first sale. Do we want to make that one hundred percent easy? Not necessarily. No one can do that for you. You have to figure out how to do it. And then when you do, you will feel growth. That's good friction. And a lot of what we think about all day internally at Shopify is how do we surface and orient you correctly around the good friction so that you grow and feel yourself growing and then trust yourself more.

Now for buyers. You think the buyers are just an entirely different creature than merchants, but that's not necessarily true. There are some components of buying where we want to get rid of the friction. So a good example is page load times. We are obsessed with page load times at Shopify. Every 50 milliseconds a page doesn't load when you're in the middle of a shopping or buying process is a little bit of broken trust, with the merchant and with the process and with everything.

You get maybe a couple of Get Out of Jail Frees, but not an infinite number of them. It's not just the inconvenience of page load times, it's breaking trust. Commerce is a dialogue. And you remember that even online commerce is still made of people metaphorically talking to each other and gesturing with their hands and negotiating back and forth. And you don't want page load times in the middle of that. Really, really breaks the process.

On the other hand, what is the good friction involved in commerce and in buying? If we went and followed through on a mission of: “get all of the friction out of commerce”, you know where we'd end up? We would just make another version of Amazon. Or another version of these things that already exist.

So not to give away too many sort of secret sauce parts of Shopify and commerce, but I think we understand we want to help bring into the world of commerce. That friction is good to get rid of, but not challenge. Challenge is important, because challenge is kind of the essence of what commerce is.

If you strip away all the challenge out of commerce, what you're left with is a convenience store. And there's a place for convenience stores. They do something useful. But it's not for merchants. That's not commerce, that's something else. And so Shopify is... Shopify isn't a place to power convenience stores. That's not what we're about.

Jim: So give me a description of like, what would a perfect merchant be for Shopify?

Alex: I don't think there's a perfect merchant. But there could be a perfect trajectory of the merchant, which is what we care about. We care a lot about trajectory. One of the things we're most proud of at Shopify is the fact that if you look at the biggest merchants selling the most GMV on our platform, a large percent of them are merchants who did not exist 10 years ago. They started out on the Shopify platform or came to us very early in their life as a merchant and grew up to be these enormous success stories.

The thing that's amazing about merchants and about commerce is that this is the most unfixed TAM in the universe. People want to grow. People want to grow their stores and grow their businesses and succeed more generally. This is the opposite of a fixed pie you have to go after.

There's no perfect, ideal merchant for us in any moment of time. If you are a tiny merchant, we want to serve you. If you're a huge merchant, we want to serve you. If you are any merchant, we want to serve you. What we care about is that you are a merchant we can help grow. It's the trajectory that we really care about. So we care about merchants, who, the first thing in the morning, they look at Shopify and the last thing they do before they check out for the evening and go play with their kids, they look at Shopify.

Jim: Yeah. I watched a documentary on antique booksellers, last night, I think it was on Prime or Netflix or whatever. And I was struck by the idea that most of them are kind of downcast. They think their industry is dying. And what I found interesting was the characters are really quirky, really smart, and they would hunt the earth to find a book.

And one of the things that was brought up was with the internet, anybody who wants whatever, a first edition of TS Eliot's poetry, they type that into Google or whatever search engine. And there it is. Do you think that certain industries are going to either disappear or radically change because of the trajectory of where things are going?

Alex: We’re still the early days of how the internet is going to change things. I don't know how you can come up with any other conclusion. I think it's worth looking at the fact that the internet... The internet as we know it has been around for what, 30 years? 25 years?

Jim: Well, yeah. In usable form, I was one of the first users of all. I bought one of the first books on Amazon, etcetera.

Alex: It's been 26 years since 1994. So let's call it 26 years. In the beginning you had the web, you had the web browser, and you had the ability for anybody to go participate. It was open. Anybody could go make a website. Anybody could go crawl around there. Anybody could go in these communities. It was quite open. It was a science experiment for some time.

I was pretty young at the time. But so I've heard, most of the rhetoric from “serious people” at the time was, “Soon, we will roll out the enterprise-grade version of the internet that is ready for real commerce.” You had this idea of the Information Superhighway was a thing that was going to get rolled out. And everybody was like, "The web is interesting. But it obviously isn't the real version. The real version is going to be far more professionally made."

Alex: And the Information Superhighway never worked out, but a more consumer friendly version of it did, which was AOL. AOL understood really well that the internet was this new thing that was exciting, and people didn't really trust it, or know how to use it. But if you made it easy for them, if you incessantly mailed CDs to their door and you made this nice onboarding experience where people kind of understood what they were doing. You told them what an AOL keyword was, and you started getting them using AOL. Then if you could have people trust you, then AOL would make all the money. And they went a long ways towards pulling that off.

AOL made a tremendous amount of progress in onboarding people onto this thing. And so naturally, one of the killer applications of this idea of connecting people was, "Oh, you'll be able to sell people things." We didn't really know how that was going to work. Initially it was stores who said,, "Okay, let's put our catalog on the internet." And then at the bottom of the catalog it would say, "Call the number and then we'll order it for you."

And so that was clearly not the real way, but people experimented with it and played around with it. But the problem was that commerce over the internet was still fairly low trust. You didn't really know if you could trust somebody on the other end of the internet. You didn't probably know what to do.

And then this incredible, magical company figured it out. That company was eBay.

eBay got it right. eBay a hundred percent realized that the internet was a place for people who obsessively cared about stuff: collectibles, Beanie Babies or trading cards or whatever it might be. And were willing to go through a lot of challenges to find what they were looking for and engage with a seller and bid on it and go through all of this friction. And at the end of the friction, you get an amazing outcome. Which is they got this very rare, special thing that they were looking for. Like the rare book sellers; they'd get their first edition TS Eliot. They went through the challenge. And at the other side of the challenge was something great.

eBay figured out a couple of things. You needed certain ways to trust the process, like getting in seller ratings and buyer ratings and making certain aspects of the process a little bit more transparent and easy. There's this book called The Perfect Store that I think has been recommended on Patrick's podcast and also generally that everyone should read.

eBay had just completely seized this new world: "The internet is this perfect forum for bringing people together to engage in this challenge of doing commerce." But then, success became eBay's worst enemy because as they got bigger, the temptation towards convenience became too strong. So you started seeing things like the Buy It Now button, which initially was fine, but it takes you down a little bit of path towards like, get rid of all the friction, get rid of all the challenge. Make this more convenient.

And then eBay started pitting sellers against each other, as you're trying to please buyers more. And as they went down this path of optimizing for getting rid of friction, they killed what made the place so uniquely magical. And eBay's still around, obviously, but it is not on the pulse of commerce like it used to be. So that was a model of selling things online. We learned a lot, it had its moment, but the draw of convenience was too strong.

Concurrently, you had this other company who had a different idea about how commerce on the internet was going to work. And that company said, "You know what? Convenience plus selection is a really good mix for the internet. If we give our buyers both of those things and they come to expect both of them, there should be a virtuous cycle we can tap into where we can reinvest all of the proceeds of convenience and selection into more convenience and selection. And this will be a really nice flywheel.”

And so that company, early on in its life, looked at a couple of different names for the business. I think it was called Cadabra originally. My favorite of the original names was relentless.com.

Jim: I loved relentless.com.

Alex: It's still, if you go to relentless.com, it still takes you to Amazon. It still works.

Anyway, Amazon has one of the great executing companies of our age. But what Amazon understands so well is that convenience ultimately is driving the bus, not commerce. Amazon is not a commerce company, they are a convenience company. And they apply that to everything. So it is not really a place where commerce happens.

Jim: Right.

Alex: And so it's great for people who want to get things conveniently. And that's a lot of things, for a lot of people. But it's not quite the same thing as shopping. You don't shop on Amazon. Amazon is a bad shopping experience.

So that is where Shopify would like to go make our mark on the world of online commerce. And so in 2020, 26 years in, eBay had their moment in the sun where they had understood shopping for that initial market. But, 20 years later, we still haven't figured it out. So Shopify really has this mission to go get that right, on behalf of our merchants, on behalf of buyers everywhere. We want to make shopping awesome.

Jamie: It's interesting that you use eBay instead of Amazon as the trust example. Because I remember last year, or maybe two years ago now, when Chris Meredith, our CIO, and I worked on this paper called Value Is Dead. We were looking at the comparisons between kind of the early manufacturing age and information age. And we read a lot about how Amazon pulled ahead early because they focused on the one-click credit card payment processing system. And that initially it was a real struggle for people to trust entering their credit card information online. But Amazon made that a real focus and kind of worked to overcome this internet trust issue that you were talking about with eBay.

Alex: So that's absolutely right. And is a really good thing to point out. Remember, in the early, early days of eBay, you had to mail eBay a check.

Jim: Yep.

Alex: The great anecdote from that book, The Perfect Store is that eBay's employee number two, I think it was, their job was opening checks in the mail that people sent them. The joke is, that's how you know when you’ve found product market fit.

What really made eBay win was connecting buyers and sellers who were so motivated to make these unique one of a kind sales that they were willing to push through anything to go do that. And that included navigating weird payment things, whether it was checks initially or getting started with PayPal. In contrast, If you were buying things for convenience on the internet, none of that was going to work. It has to be easy. It has to be one-click. Or as close to one-click as you can.

For Amazon, that was a differentiator: get your payment done, get people to trust that this payment is going to the right place. And ultimately it mattered a lot for them.

Tobi likes to say that “the web is great, but it has two critical design flaws.” The first design flaw was that payments weren't built in, even though they almost were. And that helped Amazon grow and win this whole slice of commerce. And the second flaw was that identity was not baked into the web. It was left up to websites to decide how they managed identity and how they attract people's identity. And that initially led to things like AOL having a large presence around owning people's identity.

But then down the road, this is how you get to places like Facebook who provide this incredible service for people, by giving them an identity that they can use to talk to other identities. But ultimately this turned a lot of the internet and subsequently a lot of the world of commerce into something that happened inside walled gardens. To Facebook’s credit, they've done an incredible job executing on this.

So part of our job at Shopify is to help bring our merchants into all the gardens with Facebook. And ask, "Hey, how can we bring everything that our merchants have to offer, and all of the commerce superpowers that we can give them, to where buyers are?" And to where Facebook wants all of this commerce to happen. They have been a great and really interesting partner for us to work with and learn from.

Facebook, in many ways, has done the hardest job of all. Which is, figure out how to really understand people and what they trust, and how people work. Facebook's business is understanding how people work. So we can learn a lot from them, in terms of how to best put that to work to help make commerce do well.

Jim: And another thing Dan and I were talking about yesterday was Facebook and its stranglehold on all emerging countries, all emerging economies. I wasn't aware that... We're invested in one of his funds called Anchorless, which operates in Bangladesh. And 95% of everything, commerce, communication, everything, is Facebook based.

Alex: Yeah. I remember there was a survey of some sort a few years back, I believe it was Indonesia, but I could be wrong. The survey question asked: have you used the internet in the past month? And maybe 80% of people said no. And then they asked, have you used Facebook in the past month? People are like, "Oh yeah, I'm on Facebook every day."

I don't personally know these markets very well at all, but you look at these new companies certainly like the Chinese internet giants and a lot of the relentless expansion of their international arms, but also these homegrown companies like Sea Limited that we don't know about. (And we need Julie Young to teach us about on Twitter). There is so much that Shopify can learn from these other ways that commerce can work.

Part 2: Twitter, the World’s Learning Commons

Jim: So, that brings up another thing I wanted to talk to you about, which is this idea that we share: that more and more knowledge creation is happening in the open. OSAM's motto is learn, build, share, repeat.

Alex: I like that.

Jim: And we have what we call research partners. These are people who do not work for OSAM, but we give them the data we have, which costs millions and millions a year, and these are people with mad skills and we give them access to it. And our first and probably best known writes under a pen name, Jesse Livermore. But what are your thoughts about what is driving the learning in public and where do you think it takes us?

Alex: So, this is a fascinating question. And I think about this all the time.

Generally speaking, if you look at what people are really after, in their life? People are looking for things that get them interested. People are looking for stimulation, people are looking for stuff to really gnaw their teeth into, that is interesting to them that they may not get in their day to day job, whatever it might be.

The open community of the internet is somewhere where you can find other people who are interested in those same things as you and who want to learn about those same things as you in a way that was not really possible before, without there being a substantial amount of transaction costs involved.

In the old days, if you knew about business and you wanted to go talk to other people who cared about similar areas of business as you, and trade your ideas, the only way for you to get to do that would typically be to meet somewhere that is not accessible to everybody. It'd be at the country club. That social function has existed forever: "Hey, talk shop, show off a little to each other, learn, be curious." But they were not available in the open.

The curious thing about the internet, is that the returns to being on Twitter and getting to just say whatever's on your mind and participate in FinTwit, and in all of these communities, has been radically different and in many ways follows the backwards set of rules as in the old days. About, not only what is valuable for you to participate in and what is interesting to you, but also what is considered valuable versus suspect.

I don't know about you, but I certainly remember being told: "Don't ever listen to anybody who is pitching you stock tips." Right? If they were any good, they wouldn't tell them to you, right? They would be monetizing it themselves.

Jim: Right.

Alex: “You can't afford the people whose advice you actually want.” This is no longer true, necessarily.

Jim: No, I know. Some of the best analysts on stocks are kids on the internet.

Alex: The best analysis, the best work, the most thoughtful commentary and understanding and deep dives are free.

Jim: Free, I know. It's amazing.

Alex: Now, the challenge is that, that doesn't mean they're accessible to just anybody, because you have to know which ones they are.

Jim: Right.

Alex: Right. This is an abundance problem, not a scarcity problem. This is a problem of curation and opinion and understanding how to navigate this deluge of people saying what's on their mind. It becomes very reputation-based, first of all. And Twitter is perfect for this. People have said many times that Twitter is a better LinkedIn, because looking at who people follow is an amazingly high signal way to find out who you should pay attention to.

Jim: Right.

Alex: You go find people you respect and you look at who they're following. And that is a very, very high signal about who knows what they're talking about or somebody potentially you should pay attention to. You look at someone like Matt Ball talking about media. No one is better at communicating what matters in media than Matt Ball.

Jim: I read that. I read it twice because I'm like, "This is amazing."

Alex: Everything he writes! You always learn something, it's always so smart. I think I agree with it 85 to 90% of the time, which is the perfect ratio. It should never be 100, it should be just under 100%. And best of all, it is in Matt's interest for this to be available for free, right? This is not altruism or egotism. Matt's business is for everybody to understand what he knows. And how do you do that? Well, you share your best stuff.

Jim: Yep.

Alex: Right? There's the paradox of the free versus the paid tier of the newsletter, which is that you would expect that the best stuff is in the paid tier, but in reality, the best stuff is in the free tier.

Jim: Free tier, of course it is.

Alex: Because that's how you get people to subscribe! And so Twitter is like the free tier of the world's great thinking. It's where the best thinking takes place. And you're one of the Deans of this class and you've done a remarkable thing in terms of being associated as the... the “neutral good guy” that everybody likes and is always there with the right gif. And is generally “supervising”, I think, to make sure that everybody is staying friends, which is a remarkably valuable function.

Jim: We are so simpatico on this, Alex. I agree with you 96%. And I think that properly curated Twitter is going to have... The potential of Twitter is not even being touched yet. In my opinion.

Alex: When you say the potential of Twitter, what do you see as the big potential?

Jim: So, to me, the big potential of Twitter is that it becomes a truly decentralized and yet connected intellectual marketplace where you can find and vet the very, very best minds in the world. And so, if the noise can get reduced just a bit and the signal pumped up a little bit, I honestly think it's like the extended mind of man, if you will. And also a very, very good system for preference falsification.

Alex: There's something interesting about Twitter, which is that in order to use it correctly, you need a major suspension of disbelief going on in your brain. In order to actually experience how great it is, you have to at least somewhat hold the belief that it's all stupid and silly.

Jim: Right.

Alex: Right? You have to call it The Bad Website and you have to think, at least 20%, "Jack, please delete Twitter. And we'll all be so much better off."

I'll tell you an interesting part of Twitter that I imagine many of your listeners don't know about. It's Academia Twitter; Twitter in life science research especially, which is a world that I know a little bit, I was in grad school for neuroscience some time ago. It's a world that I got to know a little bit before I went off and did other stuff.

So academia is an interesting place because there is this funnel into academia that used to work and now doesn't work. And the funnel used to be: you go get your PhD, which is an apprenticeship under somebody who really invests in you and then teaches you how things work.

And at the end of your PhD, the idea was you went and got a spot as a professor doing research somewhere. And you would teach and you do research and this pipeline worked pretty well. This worked for 100s of years, mind you; this is a very old setup. In the mid 20th century, we had this new invention, which is called the Postdoc. After your PhD, before you immediately throw yourself headfirst into being a professor and all the overhead and administrative job that creates, you take two or three years to work in someone else's lab and only do really good science. Take advantage of the fact that you're still young. You don't need the big salary yet. You can just be totally free to maximize how productive you are and go learn about what you want to do, right? And go build more expertise.

Alex: So, for a period of time, the best years of your life as a scientist was during your Postdoc. And for some people that is still true, but for a decreasing number. And the reason why is because of the pipeline of people into academia. PhD production increased and increased and increased, and the number of faculty positions did not increase at the same rate. However, no feedback signal was generated to stop producing PhD students because there is an elastic capacity in the system to accommodate more and more of them, which is called the Postdoc. (I'll get back to Twitter in a second, I promise.)

Jim: No, I'm loving this.

Alex: So, you have this expandable reservoir of Postdocs who have become the actual workhorses for life science research in recent years. They're the people who are actually doing the science and actually writing the papers and actually doing a lot of what people think happens in labs, for very low pay in this really miserable career funnel. Because you're competing against everybody else who has to do the same thing.

Now you might ask, "Why does everybody put up with this? What is the force that is holding this together?" The critical barrier to getting hired for a faculty position and really getting that job offer from a good university is getting a certain number of publications in the tier one journals. And the way that you get into those tier one journals, if you do not have an established reputation, is by being in the labs that can get you into those journals. It is a little bit about the science that you do, but really it's about being in one of those powerhouse labs that can get you into and accepted in Cell, Nature, Science, or New England Journal of Medicine.

So this is a setup where, as a young scientist, you are effectively forced to pay tribute to the established scientists in the form of being a Postdoc in their lab for potentially years and years, so they will grant you the keys into the journal, so that you can build a reputation and then get hired. And because there is not really any other way for you to build your reputation at scale in the scientific community, other than publishing in the journals, you have to pay that tribute.

And because you have to pay that tribute, the entire financial model of how science is funded has become arranged around cheap Postdocs who get paid 40 to 45K a year, being in surplus availability. There's no other place that they can go. So that's how the labor market of science works. All backed up behind a gate: the fact that there’s no other way to build a reputation.

Now, Twitter has shown up and it has really caused some problems for the established model. Because now as a young PhD student, or Postdoc, you have the ability to go direct to your audience and tell them directly what you're working on and directly participate in talking about science with people, with no barriers. Are you able to find other people? Can you talk about what's interesting to you? Can you share your work directly? This is very cool.

Jim: Very.

Alex: Very cool, right? In the short term, it's not like people are not publishing their work. The journals are still the final destination of published work. But it is very dangerous to the existing model because it is creating a short circuit around the gate keeping aspect that forces the young scientists to pay tribute to the old ones, which was, there is no other way to build a reputation. But now there is.

Jim: This is fascinating. One of my theories is that you've seen, a lot of the histrionics you've seen, from the media gatekeepers, from academia gatekeepers. Basically, my theory is that the gatekeepers know they're dying and they're very, very unhappy about it. And I mean, if we look at the media, sure. Why are they doing what they're doing? Because it's a money model. You want to attract like-minded people. So, the New York Times goes left and the Wall Street Journal goes right. The TV networks do it, but in my opinion, they're losing. And that there... I don't think there's anything that's going to stop them from falling, right? Because as you just said, this peer to peer in Twitter is unstoppable in my opinion.

Alex: It is. Although, I'll put a caveat on that, which is that... And I'm curious, I would love to know what you think about this. So, Twitter is different every day, right? What's the line, “Every day on Twitter, you wake up and you log on and see who we're mad at.” I think actually the best way this was articulated was, “Every day on Twitter there's one main character and the goal is to never be it.”

Jim: Never be that character.

Alex: Twitter is at its best when everyone is talking about the same thing. So, Twitter during NBA finals, amazing, right? Twitter during... Even during the election, honestly.

Jamie: Elon Musk's 420 tweet is always our prime example.

Alex: Twitter is great when everybody gets jolted onto the same page, for some reason. And the traditional media format is actually a good way of doing that. Because, it is not peer to peer. It is one to many. It is a broadcast format. And there's a really good synergy between those two things.

I think the most successful large example of Twitter actually working sustainably, the way that you could see it working as a business, is the sports Twitter. Or Game of Thrones. There's this incredible symbiotic relationship between the many on Twitter versus the one which is broadcast TV. And they both make each other better. And so, Twitter without the one where it's just the many, disintegrates into something that is still special, but not quite as special as when everybody is synced; when everybody is clocked into the same rhythm.

Jim: That's really a good point. So, for example, Jamie got his job at OSAM through Twitter.

Alex: Yeah.

Jim: And he had a long interview, if you will, by me reading all of his posts as the financial history guy, right? And now to be fair to Jamie, Jamie is also a very persistent guy. And he got Patrick's email by figuring out our corporate email system and asked him-

Jamie: Low level stalker stuff.

Alex: That's a great story.

Jim: ... Asked him if he could come up and have lunch with him. Patrick, unaware that Jamie lived in Washington, DC said, "Yeah, sure." So what does Jamie do? Jamie gets in his car. What time was it Jamie? 4:30 or 5:00?

Jim: 4:00 AM, out the driveway. So he could take Patrick out to lunch.

Alex: That is one of the classic hustler entrepreneur stories, right? Which is the... You finally get an investor's attention. And they're like, "Oh, let me know when you're next in New York." And you're like, "Oh, I'm actually going to be there on Monday." Buy the cheapest plane ticket to New York.

Jamie: Morgan Housel did that with Jason. Literally Jason said, "Let me know the next time you're in New York." And Morgan was like, "Oh, I'll be there tomorrow." bought an Amtrak ticket.

Alex: Oh, it's such a trope. It's a really, really good trope.

Parts 3 and 4 of the interview will be in next week’s newsletter. If you don’t want to wait that long, you can listen to the whole thing here.

If you’re looking for more things to read this week, my number one recommendation for you is the most recent issue of The Observer Effect, where Sriram Krishnan talks with Tobi Lütke about a whole range of topics - how he manages his time, personality traits and tests, Shopify’s org structure, jazz music, gaming, and two of his favourite books. It’s a sublimely good interview and I feel like reading it helped me get 1% better at my own job. (Maybe 1% is a lot. But more than zero!)

The Observer Effect: Tobi Lütke | Sriram Krishnan

Take time to read it slowly. It’s great.

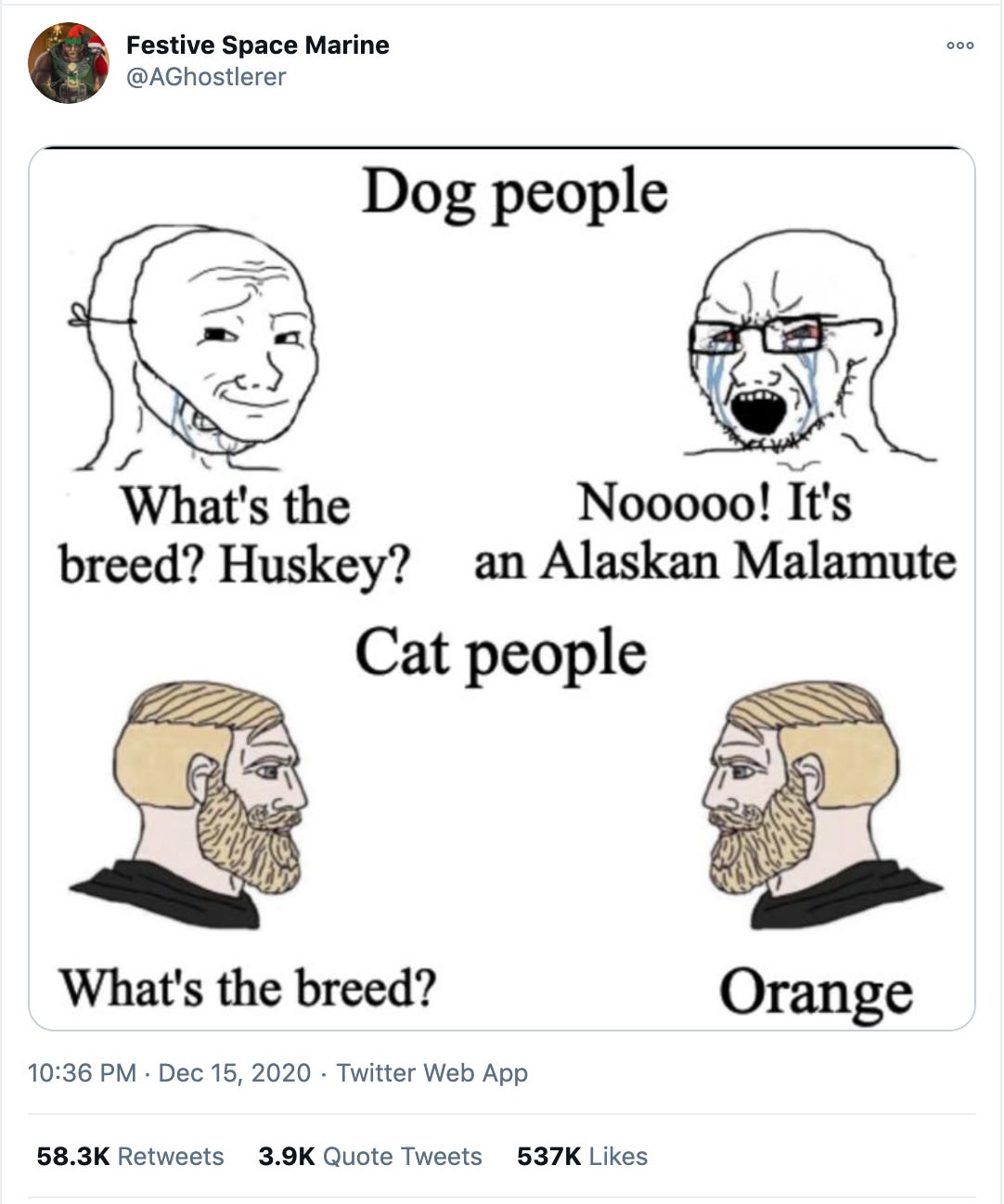

And finally, this week’s Tweet of the Week that made me laugh the hardest:

Have a great week!

Alex